Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

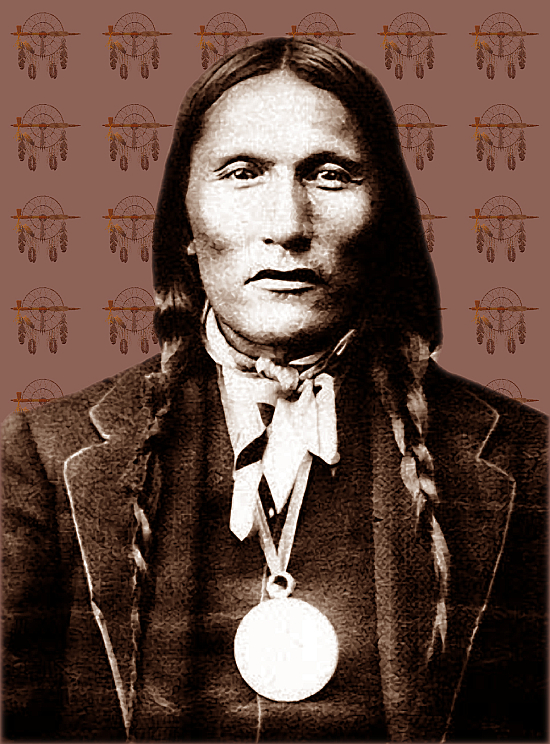

Luther Standing Bear, aka Ota Kte or Mochunozhin

Sioux Writer and Actor

"For all the great religions have preached and expounded, or have been revealed by brilliant scholars, or have been written in books and embellished in fine language with finer covers, men - all man - is still confronted with the Great Mystery."

"The old life was attuned to nature’s rhythm – bound in mystical ties to the sun, moon and stars; to the waving grasses, flowing steams and whispering winds. It is not a question… of the white man “bringing the Indian up to his plan of thought and action.” It is rather a case where the white man had better grasp some of the Indian’s spiritual strength."

"Knowledge was inherent in all things. The world was a library and its books were the stones, grass, brooks… What we learned to do what only the students of nature ever learn, and that was to feel beauty."

"I am going to venture that the man who sat on the ground in his tipi meditating on life and its meaning, accepting the kinship of all creatures, and acknowledging unity with the universe of things was infusing into his being the true essence of civilization."

"Today the children of our public schools are taught more of the history, heroes, legends, and sagas of the wold world than of the land of their birth, while they are furnished with little material on the people and institutions that are truly American."

"Knowledge was inherent in all things. The world was a library and its books were the stones, leaves, grass, brooks ... We learned to do what only the students of nature ever learn, and that was to feel beauty."

"Only to the white man was nature a “wilderness’ and only to him was the land infested with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To use it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it “wild” for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was that for us the “Wild West” began."

"There is a road in the hearts of all of us, hidden and seldom traveled, which leads to an unkown, secret place."

"He loved the earth and all things of the earth.. He knew that man's heart away from nature becomes hard, he knew the lack of respect for growing, living things soon led to the lack of respect for humans too."

"We were taught to sit still and enjoy the silence. We were taught to use our organs of smell, to look when apparently there was nothing to see, and to listen intently when all was seemingly quiet."

"Civilization has been thrust upon me... and it has not added one whit to my love for truth, honesty, and generosity."

"The old people came literally to love the soil and they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power. It was good for the skin to touch the earth and the old people liked to remove their moccasins and walk with bare feet on the sacred earth. Their tipis were built upon the earth and their altars were made of earth. The birds that flew into the air came to rest upon the earth and it was the final abiding place of all things that lived and grew. The soil was soothing, strengthening, cleansing and healing."

"As a child I understood how to give, I have forgotten this grace since I have become civilized. -"

"Children were taught that true politeness was to be defined in actions rather than in words. They were never allowed to pass between the fire and the older person or a visitor, to speak while others were speaking, or to make fun of a crippled or disfigured person. If a child thoughtlessly tried to do so, a parent, in a quiet voice, immediately set him right. Expressions such as "excuse me," "pardon me," and "so sorry" now so often lightly and unnecessarily used, are not in the Lakota language. If one chanced to injure or cause inconvenience to another wanunhecun, or "mistake," was spoken. This was sufficient to indicate that no discourtesy was intended and that what happened was accidental. Our young people, raised under old rules of courtesy, never indulged in the present habit of talking incessantly and all at the same time. To do so would have been not only impolite, but foolish; for poise, so much admired as a social grace, could not be accompanied by restlessness. Pauses were acknowledged gracefully and did not cause lack of ease or embarrassment. In talking to children, the old Lakota would place a hand on the ground and explain: "We sit in the lap of our Mother. From her we, and all other living things, come. We shall soon pass, but the place where we now rest will last forever." So we, too, learned to sit or lie on the ground and become conscious of life about us in its multitude of forms. Sometimes we boys would sit motionless and watch the swallows, the tiny ants, or perhaps some small animal at its work and ponder its industry and ingenuity; or we lay on our backs and looked long at the sky, and when the stars came out made shapes from the various groups. Everything was possessed of personality, only differing from us in form. Knowledge was inherent in all things. The world was a library and its books were the stones, leaves, grass, brooks, and the birds and animals that shared, alike with us, the storms and blessings of earth. We learned to do what only the student of nature learns, and that was to feel beauty. We never railed at the storms, the furious winds, and the biting frosts and snows. To do so intensified human futility, so whatever came we adjusted ourselves, by more effort and energy if necessary, but without complaint. Even the lightning did us no harm, for whenever it came too close, mothers and grandmothers in every tipi put cedar leaves on the coals and their magic kept danger away. Bright days and dark days were both expressions of the Great Mystery, and the Indian reveled in being close to the Great Holiness. Observation was certain to have its rewards. Interest, wonder, admiration grew, and the fact was appreciated that life was more than mere human manifestation; it was expressed in a multitude of forms. This appreciation enriched Lakota existence. Life was vivid and pulsing; nothing was casual and commonplace. The Indian lived - lived in every sense of the word - from his first to his last breath."

"Conversation was never begun at once, nor in a hurried manner. No one was quick with a question, no matter how important, and no one was pressed for an answer. A pause giving time for thought was the truly courteous way of beginning and conducting a conversation."

"From Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, there came a great unifying life force that flowed in and through all things - the flowers of the plains, blowing winds, rocks, trees, birds, animals - and was the same force that had been breathed into the first man. Thus all things were kindred, and were brought together by the same Great Mystery. Kinship with all creatures of the earth, sky, and water was a real and active principle. In the animal and bird world there existed a brotherly feeling that kept the Lakota safe among them. And so close did some of the Lakotas come to their feathered and furred friends that in true brotherhood they spoke a common tongue. The animals had rights - the right of a man's protection, the right to live, the right to multiply, the right to freedom, and the right to man's indebtedness - and in recognition of these rights the Lakota never enslaved an animal, and spared all life that was not needed for food and clothing. This concept of life and its relations with humanizing, and gave to the Lakota an abiding love. It filled his being with joy and mystery of living; it gave him reverence for all life; it made a place for all things in the scheme of existence with equal importance to all. The Lakota could not despise no creature, for all were of one blood, made by the same hand, and filled with the essence of the Great Mystery. In spirit, the Lakota were humble and meek. "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth" - this was true for the Lakota, and from the earth they inherited secrets long since forgotten. Their religion was sane, natural, and human."

"Kinship with all creatures of the earth, sky, and water was a real and active principle. In the animal and bird world there existed a brotherly feeling that kept us safe among them... The animals had rights - the right of man's protection, the right to live, the right to multiply, the right to freedom, and the right to man's indebtedness. This concept of life and its relations filled us with the joy and mystery of living; it gave us reverence for all life; it made a place for all things in the scheme of existence with equal importance to all."

"Man's heart away from nature becomes hard."

"Nothing the Great Mystery placed in the land of the Indian pleased the white man, and nothing escaped his transforming hand. Wherever forests have not been mowed down, wherever the animal is recessed in their quiet protection, wherever the earth is not bereft of four-footed life - that to him is an "unbroken wilderness." But, because for the Lakota there was no wilderness, because nature was not dangerous but hospitable, not forbidding but friendly, Lakota philosophy was healthy - free from fear and dogmatism. And here I find the great distinction between the faith of the Indian and the white man. Indian faith sought the harmony of man with his surroundings; the other sought the dominance of surroundings. In sharing, in loving all and everything, one people naturally found a due portion of the thing they sought, while, in fearing, the other found the need of conquest. For one man the world was full of beauty, for the other it was a place of sin and ugliness to be endured until he went to another world, there to become a creature of wings, half-man and half-bird. Forever one man directed his Mystery to change the world. He had made; forever this man pleaded with Him to chastise his wicked ones; and forever he implored his God to send His light to earth. Small wonder this man could not understand the other. But the old Lakota was wise. He knew that a man's heart, away from nature, becomes hard; he knew that lack of respect for growing, living things soon led to lack of respect for humans, too. So he kept his children close to nature's softening influence."

"No one was quick with a question, no matter how important, and no one was pressed for an answer. A pause giving time for thought was the truly courteous way of beginning and conducting a conversation."

"Out of the Indian approach to life there came a great freedom, an intense and absorbing respect for life, enriching faith in a Supreme Power, and principles of truth, honesty, generosity, equity, and brotherhood as a guide to mundane relations."

"Silence was meaningful with the Lakota, and his granting a space of silence before talking was done in the practice of true politeness and regardful of the rule that "though comes before speech. And in the midst of sorrow, sickness, death or misfortune of any kind, and in the presence of the notable and great, silence was the mark of respect. More powerful than words was silence with the Lakota. His strict observance of this tenet of good behavior was the reason, no doubt, for his being given the false characterization by the white man of being a stoic. He has been judged to be dumb, stupid, indifferent, and unfeeling. As a matter of truth, he was the most sympathetic of men, but his emotions of depth and sincerity were tempered with control. Silence meant to the Lakota what it meant to Disraeli, when he said "Silence is the mother of truth," for the silent man was ever to be trusted, while the man ever ready with speech was never taken seriously."

"Praise, flattery, exaggerated manners, and fine, high-sounding words were no part of Lakota politeness. Excessive manners were put down as insincere, and the constant talker was considered rude and thoughtless. Conversation was never begun at once, or in a hurried manner."

"The American Indian is of the soil, whether it be the region of forests, plains, pueblos, or mesas. He fits into the landscape, for the hand that fashioned the continent also fashioned the man for his surroundings. He once grew as naturally as the wild sunflowers; he belongs just as the buffalo belonged."

"The attempted transformation of the Indian by the white man and the chaos that has resulted are but the fruits of the white man's disobedience of a fundamental and spiritual law. "Civilization" has been thrust upon me since the days of the reservations, and it has not added one whit to my sense of justice, to my reverence for the rights of life, to my love for truth, honesty, and generosity, or to my faith in Wakan Tanka, God of the Lakotas. For after all the great religions have been preached and expounded, or have been revealed by brilliant scholars, or have been written in fine books and embellished in fine language with finer covers, man, - all man - is still confronted by the Great Mystery."

"The character of the Indian's emotion left little room in his heart for antagonism toward his fellow creatures .... For the Lakota (one of the three branches of the Sioux Nation), mountains, lakes, rivers, springs, valleys, and the woods were all in finished beauty. Winds, rain, snow, sunshine, day, night, and change of seasons were endlessly fascinating. Birds, insects, and animals filled the world with knowledge that defied the comprehension of man. The Lakota was a true naturalist - a lover of Nature. He loved the earth and all things of the earth, and the attachment grew with age. The old people came literally to love the soil and they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power. It was good for the skin to touch the earth, and the old people liked to remove their moccasins and walk with bare feet on the sacred earth. Their tipis were built upon the earth and their alters were made of earth. The birds that flew in the air came to rest upon the earth, and it was the final abiding place of all things that lived and grew. The soil was soothing, strengthening, cleansing, and healing. This is why the old Indian still sits upon the earth instead of propping himself up and away from its live giving forces. For him, to sit or lie upon the ground is to be able to think more deeply and to feel more keenly; he can see more clearly into the mysteries of life and come closer in kinship to other lives about him."

"The Lakota was a true naturalist - a lover of Nature. He loved the earth and all things of the earth, and the attachment grew with age. The old people came literally to love the soil and they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power."

"The feathered and blanketed figure of the American Indian has come to symbolize the American continent. He is the man who through centuries has been molded and sculpted by the same hand that shaped the mountains, forest, and plains, and marked the course of it rivers. The American Indian is the soil, whether it be the region of forest, plains, pueblos, or mesas. He fits into the landscape, for the hand that fashioned the continent also fashioned the man for his surroundings. He once grew as naturally as the wild sunflowers; he belongs just as the buffalo belonged. With a physique that fitted, the man developed fitting skills -- crafts which today are called American. And the body had a soul, also formed and moulded by the same master hand of harmony. Out of the Indian approach to existence there came a great freedom -- an intense and absorbing love for nature; a respect for life; enriching faith in a Supreme Power; and principles of truth, honesty, generosity, equity, and brotherhood... Becoming possessed of a fitting philosophy and art, it was by them that native man perpetuated his identity; stamped it into the history and soul of this country -- made land and man one. By living -- struggling, losing, meditating, i'm-bibing, aspiring, achieving -- he wrote himself into the ineraseable evidence -- an evidence that can be and often has been ignored, but never totally destroyed... The white man does not understand the Indian for the reason that he does not understand America. He is too far removed from its formative processes. The roots of the tree of his life have not yet grasped the rock and soil. The white man is still troubled with primitive fears; he still has in his consciousness the perils of this frontier continent, some of its fastnesses not yet having yielded to his questing footsteps and inquiring eyes. The man from Europe is still a foreigner and an alien. But in the Indian the spirit of the land is still vested; it will be until other men are able to divine and meet its rhythms... When the Indian has forgotten the music of his forefathers, when the sound of the tom-tom is no more, when the memory of his heroes is no longer told in story ... he will be dead. When from him has been taken all that is his, all that he has visioned in nature, all that has come to him from infinite sources, he then, truly, will be a dead Indian.""

"There is a road in the hearts of all of us, hidden and seldom traveled, which leads to an unknown, secret place. The old people came literally to love the soil, and they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power. Their teepees were built upon the earth and their altars were made of earth. The soul was soothing, strengthening, cleansing, and healing. That is why the old Indian still sits upon the earth instead of propping himself up and away from its life giving forces. For him, to sit or lie upon the ground is to be able to think more deeply and to feel more keenly. He can see more clearly into the mysteries of life and come closer in kinship to other lives about him."

"Wherever forests have not been mowed down, wherever the animal is recessed in their quiet protection, wherever the earth is not bereft of four-footed life - that to the white man is an 'unbroken wilderness.' But for us there was no wilderness, nature was not dangerous but hospitable, not forbidding but friendly. Our faith sought the harmony of man with his surroundings; the other sought the dominance of surroundings. For us, the world was full of beauty; for the other, it was a place to be endured until he went to another world. But we were wise. We knew that man's heart, away from nature, becomes hard."

"The old Lakota was wise. He knew that man's heart away from nature becomes hard; he knew that lack of respect for growing, living things soon led to lack of respect for humans, too."

"The white man does not understand America. He is far removed from its formative processes. The roots of the tree of his life have not yet grasped the rock and the soil. The white man is still troubled by primitive fears; he still has in his consciousness the perils of this frontier continent, some of it not yet having yielded to his questing footsteps and inquiring eyes. He shudders still with the memory of the loss of his forefathers upon its scorching deserts and forbidding mountaintops. The man from Europe is still a foreigner and an alien. And he still hates the man who questioned his path across the continent. But in the Indian the spirit of the land is still vested; it will be a long time until other men are able to divine and meet its rhythm. Men must be born and reborn to belong. Their bodies must be formed of the dust of their forefathers' bones."