Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

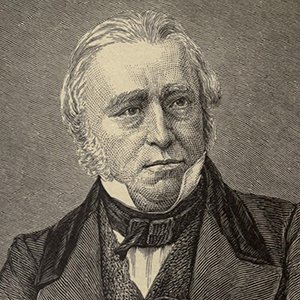

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"The highest proof of virtue is to possess boundless power without abusing it."

"To every man upon this earth Death cometh soon or late; And how can man die better Than facing fearful odds For the ashes of his fathers And the temples of his gods? "

"A church is disaffected when it is persecuted, quiet when it is tolerated, and actively loyal when it is favored and cherished."

"A code is almost the only blessing, perhaps it is the only blessing, which absolute governments are better fitted to confer on a nation than popular governments. The work of digesting a vast and artificial system of unwritten jurisprudence is far more easily performed, and far better performed, by few minds than by many, by a Napoleon than by a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Peers, by a government like that of Prussia or Denmark than by a government like that of England. A quiet knot of two or three veteran jurists is an infinitely better machinery for such a purpose than a large popular assembly divided, as such assemblies almost always are, into adverse factions."

"A deep melancholy took possession of him, and gave a dark tinge to all his views of human nature and human destiny."

"A few more days, and this essay will follow the Defensio Populi to the dust and silence of the upper shelf... For a month or two it will occupy a few minutes of chat in every drawing-room, and a few columns in every magazine; and it will then be withdrawn, to make room for the forthcoming novelties."

"A great writer is the friend and benefactor of his readers."

"A large part of the nation is certainly desirous of a reform in the representative system. How large that part may be, and how strong its desires on the subject may be, it is difficult to say. It is only at intervals that the clamour on the subject is loud and vehement. But it seems to us that, during the remissions, the feeling gathers strength, and that every successive burst is more violent than that which preceded it. The public attention may be for a time diverted to the Catholic claims or the Mercantile code; but it is probable that at no very distant period, perhaps in the lifetime of the present generation, all other questions will merge in that which is, in a certain degree, connected with them all."

"A good constitution is infinitely better than the best despot."

"A historian such as we have been attempting to describe would indeed be an intellectual prodigy. In his mind powers scarcely compatible with each other must be tempered into an exquisite harmony. We shall sooner see another Shakespeare or another Homer. The highest excellence to which any single faculty can be brought would be less surprising than such a happy and delicate combination of qualities. Yet the contemplation of imaginary models is not an unpleasant or useless employment of the mind. It cannot indeed produce perfection; but it produces improvement and nourishes that generous and liberal fastidiousness which is not inconsistent with the strongest sensibility to merit, and which, while it exalts our conceptions of the art, does not render us unjust to the artist."

"A contemporary historian, says Mr. Thackeray, describes Mr. Pitt’s first speech as superior even to the models of ancient eloquence. According to Tindal, it was more ornamented than the speeches of Demosthenes and less diffuse than those of Cicero. This unmeaning phrase has been a hundred times quoted. That it should ever have been quoted, except to be laughed at, is strange. The vogue which it has obtained may serve to show in how slovenly a way most people are content to think. Did Tindal, who first used it, or Archdeacon Coxe and Mr. Thackeray, who have borrowed it, ever in their lives hear any speaking which did not deserve the same compliment? Did they ever hear speaking less ornamented than that of Demosthenes, or more diffuse than that of Cicero? We know no living orator, from Lord Brougham down to Mr. Hunt, who is not entitled to the same eulogy. It would be no very flattering compliment to a man’s figure to say that he was taller than the Polish Count, and shorter than Giant O’Brien, fatter than the Anatomie Vivante, and more slender than Daniel Lambert."

"A history in which every particular incident may be true may on the whole be false. The circumstances which have most influence on the happiness of mankind, the changes of manners and morals, the transition of communities from poverty to wealth, from ignorance to knowledge, from ferocity to humanity,—these are, for the most part, noiseless revolutions. Their progress is rarely indicated by what historians are pleased to call important events. They are not achieved by armies, or enacted by senates. They are sanctioned by no treaties, and recorded in no archives. They are carried on in every school, in every church, behind ten thousand counters, at ten thousand firesides. The upper current of society presents no certain criterion by which we can judge of the direction in which the under current flows. We read of defeats and victories. But we know that many nations may be miserable amidst victories, and prosperous amidst defeats. We read of the fall of wise ministers and of the rise of profligate favourites. But we must remember how small a proportion of the good or evil effected by a single statesman can bear to the good or evil of a great social system."

"A man who has never looked on Niagra has but a faint idea of a cataract; and he who has not read Barère's Memoirs may be said not to know what it is to lie."

"A man possessed of splendid talents, which he often abused, and of a sound judgment, the admonitions of which he often neglected; a man who succeeded only in an inferior department of his art, but who in that department succeeded pre-eminently."

"A most idle and contemptible controversy had arisen in France touching the comparative merit of the ancient and modern writers. It was certainly not to be expected that in that age the question would be tried according to those large and philosophical principles of criticism which guided the judgments of Lessing and of Herder. But it might have been expected that those who undertook to decide the point would at least take the trouble to read and understand the authors on whose merits they were to pronounce. Now, it is no exaggeration to say that among the disputants who clamoured, some for the ancients and some for the moderns, very few were decently acquainted with either ancient or modern literature, and hardly one was well acquainted with both. In Racine’s amusing preface to the Iphigénie the reader may find noticed a most ridiculous mistake into which one of the champions of the moderns fell about a passage in the Alcestis of Euripides. Another writer is so inconceivably ignorant as to blame Homer for mixing the four Greek dialects, Doric, Ionic, Æolic, and Attic, just, says he, as if a French poet were to put Gascon phrases and Picard phrases into the midst of his pure Parisian writing. On the other hand, it is no exaggeration to say that the defenders of the ancients were entirely unacquainted with the greatest productions of later times; nor, indeed, were the defenders of the moderns better informed. The parallels which were instituted in the course of this dispute are inexpressibly ludicrous. Balzac was selected as the rival of Cicero. Corneille was said to unite the merits of Æschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. We should like to see a Prometheus after Corneille’s fashion. The Provincial Letters, masterpieces undoubtedly of reasoning, wit, and eloquence, were pronounced to be superior to all the writings of Plato, Cicero, and Lucian together, particularly in the art of dialogue; an art in which, as it happens, Plato far excelled all men, and in which Pascal, great and admirable in other respects, is notoriously very deficient."

"A page digested is better than a volume hurriedly read."

"A man who wishes to serve the cause of religion ought to hesitate long before he stakes the truth of religion on the event of a controversy respecting facts in the physical world. For a time he may succeed in making a theory which he dislikes unpopular by persuading the public that it contradicts the Scriptures and is inconsistent with the attributes of the Deity. But if at last an overwhelming force of evidence proves this maligned theory to be true, what is the effect of the arguments by which the objector has attempted to prove that it is irreconcilable with natural and revealed religion? Merely this, to make men infidels. Like the Israelites in their battle with the Philistines, he has presumptuously and without warrant brought down the ark of God into the camp as a means of insuring victory; and the consequence of this profanation is that, when the battle is lost, the ark is taken."

"A people which takes no pride in the noble achievements of remote ancestors will never achieve anything worthy to be remembered with pride by remote descendants."

"A system in which the two great commandments are to hate your neighbor and to love your neighbor's wife."

"A single breaker may recede; but the tide is evidently coming in."

"A propensity which, for want of a better name, we will venture to christen Boswellism."

"A thief is condemned to be hanged. On the eve of the day fixed for the execution a turnkey enters his cell and tells him that all is safe, that he has only to slip out, that his friends are waiting in the neighbourhood with disguises, and that a passage is taken for him in an American packet. Now, it is clearly for the greatest happiness of society that the thief should be hanged and the corrupt turnkey exposed and punished. Will the Westminster Review tell us that it is for the greatest happiness of the thief to summon the head jailer and tell the whole story? Now, either it is for the greatest happiness of a thief to be hanged or it is not. If it is, then the argument by which the Westminster Review attempts to prove that men do not promote their own happiness by thieving, falls to the ground. If it is not, then there are men whose greatest happiness is at variance with the greatest happiness of the community."

"A tact which surpassed the tact of her sex as much as the tact of her sex surpasses the tact of ours."

"A truly great historian would reclaim those materials which the novelist has appropriated. The history of the government, and the history of the people, would be exhibited in that mode in which alone they can be exhibited justly, in inseparable conjunction and intermixture. We should not then have to look for the wars and votes of the Puritans in Clarendon, and for their phraseology in Old Mortality; for one-half of King James in Hume, and for the other half in the Fortunes of Nigel. The early part of our imaginary history would be rich with colouring from romance, ballad, and chronicle. We should find ourselves in the company of knights such as those of Froissart, and of pilgrims such as those who rode with Chaucer from the Tabard. Society would be shown from the highest to the lowest,—from the royal cloth of state to the den of the outlaw; from the throne of the legate to the chimney-corner where the begging friar regaled himself. Palmers, minstrels, crusaders,—the stately monastery, with the good cheer in its refectory and the high mass in its chapel,—the manor-house, with its hunting and hawking,—the tournament, with the heralds and ladies, the trumpets and the cloth of gold,—would give truth and life to the representation. We should perceive, in a thousand slight touches, the importance of the privileged burgher, and the fierce and haughty spirit which swelled under the collar of the degraded villain. The revival of letters would not merely be described in a few magnificent periods. We should discern, in innumerable particulars, the fermentation of mind, the eager appetite for knowledge, which distinguished the sixteenth from the fifteenth century. In the Reformation we should see, not merely a schism which changed the ecclesiastical constitution of England and the mutual relations of the European powers, but a moral war which raged in every family, which set the father against the son, and the son against the father, the mother against the daughter, and the daughter against the mother. Henry would be painted with the skill of Tacitus. We should have the change of his character from his profuse and joyous youth to his savage and imperious old age. We should perceive the gradual progress of selfish and tyrannical passions in a mind not naturally insensible or ungenerous; and to the last we should detect some remains of that open and noble temper which endeared him to a people whom he oppressed, struggling with the hardness of despotism and the irritability of disease."

"Alas for human nature, that the wounds of vanity should smart and bleed so much longer than the wounds of affection!"

"After the wars of York and Lancaster, the links which connected the nobility and the commonalty became closer and more numerous than ever."

"A writer who describes visible objects falsely and violates the propriety of character, a writer who makes the mountains nod their drowsy heads at night, or a dying man take leave of the world with a rant like Maximin, may be said, in the high and just sense of the phrase, to write incorrectly. He violates the first great law of his art. His imitation is altogether unlike the thing imitated. The four poets who are most eminently free from incorrectness of this description are Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton. They are, therefore, in one sense, and that the best sense, the most correct of poets."

"Almost all the modern historians of Greece have shown the grossest ignorance of the most obvious phenomena of human nature. In their representations the generals and statesmen of antiquity are absolutely divested of all individuality. They are personifications; they are passions, talents, opinions, virtues, vices, but not men. Inconsistency is a thing of which these writers have no notion. That a man may have been liberal in his youth and avaricious in his age, cruel to one enemy and merciful to another, is to them utterly inconceivable. If the facts be undeniable, they suppose some strange and deep design in order to explain what, as every one who has observed his own mind knows, needs no explanation at all. This is a mode of writing very acceptable to the multitude, who have always been accustomed to make gods and dæmons out of men very little better or worse than themselves; but it appears contemptible to all who have watched the changes of human character,—to all who have observed the influence of time, of circumstances, and of associates, on mankind,—to all who have seen a hero in the gout, a democrat in the church, a pedant in love, or a philosopher in liquor. This practice of painting in nothing but black or white is unpardonable even in the drama. It is the great fault of Alfieri; and how much it injures the effect of his compositions will be obvious to every one who will compare his Rosamunda with the Lady Macbeth of Shakespeare. The one is a wicked woman; the other is a fiend. Her only feeling is hatred; all her words are curses. We are at once shocked and fatigued by the spectacle of such raving cruelty, excited by no provocation, repeatedly changing its object, and constant in nothing but its inextinguishable thirst for blood."

"All the great enigmas which perplex the natural theologian are the same in all ages. The ingenuity of a people just emerging from barbarism is quite sufficient to propound them. The genius of Locke or Clarke is quite unable to solve them. It is a mistake to imagine that subtle speculations touching the Divine attributes, the origin of evil, the necessity of human actions, the foundation of moral obligation, imply any high degree of intellectual culture. Such speculations, on the contrary, are in a peculiar manner the delight of intelligent children and of half-civilized men. The number of boys is not small who, at fourteen, have thought enough on these questions to be fully entitled to the praise which Voltaire gives to Zadig: Il en savait ce qu’on en a su dans tous les âges; c’est-à-dire, fort peu de chose. The book of Job shows that long before letters and arts were known to Ionia these vexing questions were debated with no common skill and eloquence under the tents of the Idumean Emirs; nor has human reason in the course of three thousand years discovered any satisfactory solution of the riddles which perplexed Eliphaz and Zophar."

"All his natural and all his acquired powers fitted him to found a good critical school of poetry. Indeed, he earned his reforms too far for his age. After his death our literature retrograded; and a century was necessary to bring it back to the point at which he left it. The general soundness and healthfulness of his mental constitution, his information, of vast superficies though of small volume, his wit, scarcely inferior to that of the most distinguished followers of Donne, his eloquence, grave, deliberate, and commanding, could not save him from disgraceful failure as a rival of Shakespeare, but raised him far above the level of Boileau. His command of language was immense. With him died the secret of the old poetical diction of England,—the art of producing rich effects by familiar words. In the following century it was as completely lost as the Gothic method of painting glass, and was but poorly supplied by the laborious and tessellated imitations of Mason and Gray. On the other hand, he was the first writer under whose skilful management the scientific vocabulary fell into natural and pleasing verse. In this department he succeeded as completely as his contemporary Gibbons succeeded in the similar enterprise of carving the most delicate flowers from heart of oak. The toughest and most knotty parts of language became ductile at his touch. His versification in the same manner, while it gave the first model of that neatness and precision which the following generation esteemed so highly, exhibited at the same time the last examples of nobleness, freedom, variety of pause, and cadence. His tragedies in rhyme, however worthless in themselves, had at least served the purpose of nonsense-verses: they had taught him all the arts of melody which the heroic couplet admits. For bombast, his prevailing vice, his new subjects gave little opportunity; his better taste gradually discarded it."

"Already we seem to ourselves to perceive the signs of unquiet times, the vague presentiment of something great and strange which pervades the community, the restless and turbid hopes of those who have everything to gain, the dimly-hinted forebodings of those who have everything to lose. Many indications might be mentioned, in themselves indeed as insignificant as straws; but even the direction of a straw, to borrow the illustration of Bacon, will show from what quarter the storm is setting in."

"Against misgovernment such as then afflicted Bengal it was impossible to struggle. The superior intelligence and energy of the dominant class made their power irresistible. A war of Bengalees against Englishmen was like a war of sheep against wolves, of men against demons. The only protection which the conquered could find was in the moderation, the clemency, the enlarged policy of the conquerors. That protection, at a later period, they found. But at first English power came among them unaccompanied by English morality. There was an interval between the time at which they became our subjects and the time at which we began to reflect that we were bound to discharge towards them the duties of rulers. During that interval the business of a servant of the Company was simply to wring out of the natives a hundred or two hundred thousand pounds as speedily as possible, that he might return home before his constitution had suffered from the heat, to marry a peer’s daughter, to buy rotten boroughs in Cornwall, and to give balls in St. James’s Square."

"All wise statesmen have agreed to consider the prosperity or adversity of nations as made up of the happiness or misery of individuals, and to reject as chimerical all notions of a public interest of the community distinct from the interest of the component parts. It is therefore strange that those whose office it is to supply statesmen with examples and warnings should omit, as too mean for the dignity of history, circumstances which exert the most extensive influence on the state of society. In general, the under current of human life flows steadily on, unruffled by the storms which agitate the surface. The happiness of the many commonly depends on causes independent of victories and defeats, of revolutions or restorations,—causes which can be regulated by no laws, and which are recorded in no archives. These causes are the things which it is of main importance to us to know, not how the Lacedæmonian phalanx was broken at Leuctra,—not whether Alexander died of poison or of disease. History without these is a shell without a kernel; and such is almost all the history which is extant in the world. Paltry skirmishes and plots are reported with absurd and useless minuteness; but improvements the most essential to the comfort of human life extend themselves over the world, and introduce themselves into every cottage, before any annalist can condescend, from the dignity of writing about generals and ambassadors, to take the least notice of them. Thus the progress of the most salutary inventions and discoveries is buried in impenetrable mystery; mankind are deprived of a most useful species of knowledge, and their benefactors of their honest fame. In the mean time every child knows by heart the dates and adventures of a long line of barbarian kings. The history of nations, in the sense in which I use the word, is often best studied in works not professedly historical. Thucydides, as far as he goes, is an excellent writer; yet he affords us far less knowledge of the most important particulars relating to Athens than Plato or Aristophanes. The little treatise of Xenophon on Domestic Economy contains more historical information than all the seven books of his Hellenics. The same may be said of the Satires of Horace, of the letters of Cicero, of the novels of Le Sage, of the memoirs of Marmontel. Many others might be mentioned; but these sufficiently illustrate my meaning."

"An acre in Middlesex is better than a principally in Utopia. The smallest actual good is better than the most magnificent promises of impossibilities. The wise man of the Stoics would, no doubt, be a grander object than a steam-engine. But there are steam-engines. And the wise man of the Stoics is yet to be born. A philosophy which should enable a man to feel perfectly happy while in agonies of pain would be better than a philosophy which assuages pain. But we know that there are remedies which will assuage pain; and we know that the ancient sages liked the toothache just as little as their neighbours. A philosophy which should extinguish cupidity would be better than a philosophy which should devise laws for the security of property. But it is possible to make laws which shall, to a very great extent, secure property. And we do not understand how any motives which the ancient philosophy furnished could extinguish cupidity. We know, indeed, that the philosophers were no better than other men. From the testimony of friends as well as of foes, from the confessions of Epictetus and Seneca, as well as from the sneers of Lucian and the fierce invectives of Juvenal, it is plain that these teachers of virtue had all the vices of their neighbours, with the additional vice of hypocrisy."

"And as to its nature, ask any Englishman who has ever travelled in the Southern States. Jobbers go about from plantation to plantation looking out for proprietors who are not easy in their circumstances, and who are likely to sell cheap. A black boy is picked up here; a black girl there. The dearest ties of nature and of marriage are torn asunder as rudely as they were ever torn asunder by any slave captain on the coast of Guinea. A gang of three or four hundred negroes is made up; and then these wretches, handcuffed, fettered, guarded by armed men, are driven southward, as you would drive—or rather as you would not drive—a herd of oxen to Smithfield, that they may undergo the deadly labour of the sugar-mill near the mouth of the Mississippi. A very few years of that labour in that climate suffice to send the stoutest African to his grave. But he can well be spared. While he is fast sinking into premature old age, negro boys in Virginia are growing up as fast into vigorous manhood to supply the void which cruelty is making in Louisiana. God forbid that I should extenuate the horrors of the slave-trade in any form! But I do think this its worst form. Bad enough is it that civilized men should sail to an uncivilized quarter of the world where slavery exists, should there buy wretched barbarians, and should carry them away to labour in a distant land: bad enough! But that a civilized man, a baptized man, a man proud of being a citizen of a free State, a man frequenting a Christian church, should breed slaves for exportation, and … should see children … gambolling around him from infancy, should watch their growth, should become familiar with their faces, and should then sell them for four or five hundred dollars a head, and send them to lead in a remote country a life which is a lingering death, a life about which the best thing that can be said is that it is sure to be short,—this does, I own, excite a horror exceeding even the horror excited by that slave-trade which is the curse of the African coast. And mark: I am not speaking of any rare case, of any instance of eccentric depravity. I am speaking of a trade as regular as the trade in pigs between Dublin and Liverpool, or as the trade in coals between the Tyne and the Thames."

"And how can man die better than facing fearful odds, for the ashes of his fathers, and the temples of his Gods?"

"And how stands the fact? Have not almost all the governments in the world always been in the wrong on religious subjects? Mr. Gladstone, we imagine, would say that, except in the time of Constantine, of Jovian, and of a very few of their successors, and occasionally in England since the Reformation, no government has ever been sincerely friendly to the pure and apostolical Church of Christ. If, therefore, it be true that every ruler is bound in conscience to use his power for the propagation of his own religion, it will follow that, for one ruler who has been bound in conscience to use his power for the propagation of truth, a thousand have been bound in conscience to use their power for the propagation of falsehood. Surely this is a conclusion from which common sense recoils. Surely, if experience shows that a certain machine, when used to produce a certain effect, does not produce that effect once in a thousand times, but produces, in the vast majority of cases, an effect directly contrary, we cannot be wrong in saying that it is not a machine of which the principal end is to be so used."

"And to say that society ought to be governed by the opinion of the wisest and best, though true, is useless. Whose opinion is to decide who are the wisest and best?"

"American democracy must be a failure because it places the supreme authority in the hands of the poorest and most ignorant part of the society."

"And what, after all, is the security which this training gives to governments? Mr. Southey would scarcely propose that discussion should be more effectually shackled, that public opinion should be more strictly disciplined into conformity with established institutions, than in Spain and Italy. Yet we know that the restraints which exist in Spain and Italy have not prevented atheism from spreading among the educated classes, and especially among those whose office it is to minister at the altars of God. All our readers know how, at the time of the French Revolution, priest after priest came forward to declare that his doctrine, his ministry, his whole life, had been a lie, a mummery, during which he could scarcely compose his countenance sufficiently to carry on the imposture."

"And has poetry no end, no eternal and immutable principles? Is poetry, like heraldry, mere matter of arbitrary regulation? The heralds tell us that certain scutcheons and bearings denote certain conditions, and that to put colours on colours or metals on metals is false blazonry. If all this were reversed, if every coat of arms in Europe were new-fashioned, if it were decreed that or should never be placed but on argent, or argent but on or, that illegitimacy should be denoted by a lozenge, and widowhood by a bend, the new science would be just as good as the old science, because the new and the old would both be good for nothing. The mummery of Portcullis and Rouge Dragon, as it has no other value than that which caprice has assigned to it, may well submit to any laws which caprice may impose on it. But it is not so with that great imitative art to the power of which all ages, the rudest and the most enlightened, bear witness. Since its first great masterpieces were produced, every thing that is changeable in this world has been changed. Civilization has been gained, lost, gained again. Religions, and languages, and forms of government, and usages of private life, and modes of thinking, all have undergone a succession of revolutions. Everything has passed away but the great features of nature, and the heart of man, and the miracles of that art of which it is the office to reflect back the heart of man and the features of nature. Those two strange old poems, the wonder of ninety generations, still retain all their freshness. They still command the veneration of minds enriched by the literature of many nations and ages. They are still, even in wretched translations, the delight of school-boys. Having survived ten thousand capricious fashions, having seen successive codes of criticism become obsolete, they still remain to us, immortal with the immortality of truth, the same when perused in the study of an English scholar as when they were first chanted at the banquet of an Ionian prince."

"And she (the Roman Catholic Church) may still exist in undiminished vigor, when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul's."

"And why not? The critic is ready with a reason, a lady’s reason. Such lines, says he, are not, it must be allowed, unpleasing to the ear; but the redundant syllable ought to be confined to the drama, and not admitted into epic poetry. As to the redundant syllable in heroic rhyme on serious subjects, it has been, from the time of Pope downward, proscribed by the general consent of all the correct school. No magazine would have admitted so incorrect a couplet as that of Drayton:"

"As Dryden was unable to render his plays interesting by means of that which is the peculiar and appropriate excellence of the drama, it was necessary that he should find some substitute for it. In his comedies he supplied its place sometimes by wit, but more frequently by intrigue, by disguises, mistakes of persons, dialogues at cross-purposes, hair-breadth escapes, perplexing concealments, and surprising disclosures. He thus succeeded at least in making these pieces very amusing."

"Ariosto tells a pretty story of a fairy, who, by some mysterious law of her nature, was condemned to appear at certain seasons in the form of a foul and poisonous snake. Those who injured her during the period of her disguise were forever excluded from participation in the blessings which she bestowed. But to those who, in spite of her loathsome aspect, pitied and protected her, she afterwards revealed herself in the beautiful and celestial form which was natural to her, accompanied their steps, granted all their wishes, filled their houses with wealth, made them happy in love and victorious in war. Such a spirit is Liberty. At times she takes the form of a hateful reptile. She grovels, she hisses, she stings. But woe to those who in disgust shall venture to crush her! And happy are those who, having dared to receive her in her degraded and frightful shape, shall at length be rewarded by her in the time of her beauty and her glory!"

"As civilization advances, poetry almost necessarily declines."

"Another law of heroic rhyme, which, fifty years ago, was considered as fundamental, was, that there should be a pause, a comma at least, at the end of every couplet. It was also provided that there should never be a full stop except at the end of a line."

"As far as mere diction was concerned, indeed, Mr. Fox did his best to avoid those faults which the habit of public speaking is likely to generate. He was so nervously apprehensive of sliding into some colloquial incorrectness, of debasing his style by a mixture of Parliamentary slang, that he ran into the opposite error, and purified his vocabulary with a scrupulosity unknown to any purist. Ciceronem Allobroga dixit. He would not allow Addison, Bolingbroke, or Middleton to be a sufficient authority for an expression. He declared that he would use no word which was not to be found in Dryden. In any other person we should have called this solicitude mere foppery; and, in spite of all our admiration for Mr. Fox, we cannot but think that his extreme attention to the petty niceties of language was hardly worthy of so manly and so capacious an understanding."

"Another of Addison’s favourite companions was Ambrose Phillips, a good whig and a middling poet, who had the honour of bringing into fashion a species of composition which has been called after his name, Namby-Pamby."

"As freedom is the only safeguard of governments, so are order and moderation generally necessary to preserve freedom."