Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

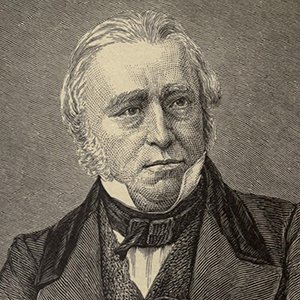

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"As in every human character so in every transaction there is a mixture of good and evil: a little exaggeration, a little suppression, a judicious use of epithets, a watchful and searching skepticism with respect to the evidence on one side, a convenient credulity with respect to every report or tradition on the other, may easily make a saint of Laud, or a tyrant of Henry the Fourth."

"As to some of the ends of civil government, all people are agreed. That it is designed to protect our persons and our property, that it is designed to compel us to satisfy our wants, not by rapine, but by industry, that it is designed to compel us to decide our differences, not by the strong hand, but by arbitration, that it is designed to direct our whole force, as that of one man, against any other society which may offer us injury, these are propositions which will hardly be disputed."

"As the development of the mind proceeds, symbols, instead of being employed to convey images, are substituted for them. Civilized men think as they trade, not in kind but by means of a circulating medium. In these circumstances the sciences improve rapidly, and criticism among the rest; but poetry, in the historical sense of the word, disappears. Then comes the dotage of the fine arts,—a second childhood, as feeble as the former, and more hopeless. This is the age of critical poetry, of poetry by courtesy, of poetry to which the memory, the judgment, and the wit contribute far more than the imagination. We readily allow that many works of this description are excellent: we will not contend with those who think them more valuable than the great powers of an earlier period. We only maintain that they belong to a different species of composition, and are produced by a different faculty."

"As it has been in science, so it has been in literature. Compare the literary acquirements of the great men of the thirteenth century with those which will be within the reach of many who will frequent our reading-room. As to Greek learning, the profound man of the thirteenth century was absolutely on a par with the superficial man of the nineteenth. In the modern languages there was not six hundred years ago a single volume which is now read. The library of our profound scholar must have consisted entirely of Latin books. We will suppose him to have had both a large and choice collection. We will allow him thirty, nay, forty, manuscripts, and among them a Virgil, a Terence, a Lucian, an Ovid, a Statius, a great deal of Livy, a great deal of Cicero. In allowing him all this we are dealing most liberally with him; for it is much more likely that his shelves were filled with treatises on school divinity and canon law, composed by writers whose names the world has very wisely forgotten. But even if we suppose him to have possessed all that is most valuable in the literature of Rome, I say with perfect confidence that, both in respect of intellectual improvement and in respect of intellectual pleasures, he was far less favourably situated than a man who now, knowing only the English language, has a bookcase filled with the best English works. Our great man of the middle ages could not form any conception of any tragedy approaching Macbeth or Lear, or of any comedy equal to Henry the Fourth or Twelfth Night. The best epic poem that he had read was far inferior to the Paradise Lost; and all the tomes of his philosophers were not worth a page of the Novum Organum."

"At his first appearance in Parliament he showed himself superior to all his contemporaries in command of language. He could pour forth a long succession of round and stately periods, without premeditation, without ever pausing for a word, without ever repeating a word, in a voice of silver clearness, and with a pronunciation so articulate that not a letter was slurred over. He had less amplitude of mind and less richness of imagination than Burke, less ingenuity than Windham, less wit than Sheridan, less perfect mastery of dialectical fence, and less of that higher sort of eloquence which consists of reason and passion fused together, than Fox. Yet the almost unanimous judgment of those who were in the habit of listening to that remarkable race of men placed Pitt, as a speaker, above Burke, above Windham, above Sheridan, and not below Fox. His declamation was copious, polished, and splendid. In power of sarcasm he was probably not surpassed by any speaker, ancient or modern; and of this formidable weapon he made merciless use. In two parts of the oratorical art which are of the highest value to a minister of state he was singularly expert. No one knew better how to be luminous or how to be obscure."

"At this conjuncture—a conjuncture of unrivalled interest in the history of letters—a man never to be mentioned without reverence by every lover of letters held the highest place in Europe. Our just attachment to that Protestant faith to which our country owes so much must not prevent us from paying the tribute which on this occasion and this place justice and gratitude demand to the founder of the University of Glasgow, the greatest of the restorers of learning, Pope Nicholas the Fifth. He had sprung from the common people; but his abilities and his condition had early attracted the notice of the great. He had studied much and travelled far. He had visited Britain, which in wealth and refinement was to his native Tuscany what the back settlements of America now are to Britain. He had lived with the merchant princes of Florence, those men who first ennobled trade by making trade the ally of philosophy, of eloquence, and taste. It was he who, under the protection of the munificent and discerning Cosmo, arranged the first public library that modern Europe possessed. From privacy your founder rose to a throne; but on the throne he never forgot the studies which had been his delight in privacy. He was the centre of an illustrious group, composed partly of the last great scholars of Greece and partly of the first great scholars of Italy, Theodore Gaza and George of Trebizond, Bessarion and Filelfo, Marsilio and Poggio Bracciolini. By him was founded the Vatican Library, then and long after the most precious and the most extensive collection of books in the world. By him were carefully preserved the most valuable intellectual treasures which had been snatched from the wreck of the Byzantine empire. His agents were to be found everywhere, in the bazaars of the farthest East, in the monasteries of the farthest West, purchasing or copying worm-eaten parchments on which were traced words worthy of immortality. Under his patronage were prepared accurate Latin versions of many precious remains of Greek poets and philosophers. But no department of literature owes so much to him as history. By him were introduced to the knowledge of Western Europe two great and unrivalled models of historical composition, the work of Herodotus and the work of Thucydides. By him, too, our ancestors were first made acquainted with the graceful and lucid simplicity of Xenophon and with the manly good sense of Polybius."

"At length the time arrived when the barren philosophy which had, during so many ages, employed the faculties of the ablest of men, was destined to fall. It had worn many shapes. It had mingled itself with many creeds. It had survived revolutions in which empires, religions, languages, races, had perished. Driven from its ancient haunts, it had taken sanctuary in that Church which it had persecuted, and had, like the daring fiends of the poet, placed its seat"

"Assuredly one fact which does not directly affect our own interests, considered in itself, is no better worth knowing than another fact. The fact that there is a snake in a pyramid, or the fact that Hannibal crossed the Alps, are in themselves as unprofitable to us as the fact that there is a green blind in a particular house in Threadneedle Street, or the fact that a Mr. Smith comes into the city every morning on the top of one of the Blackwall stages. But it is certain that those who will not crack the shell of history will not get at the kernel. Johnson, with hasty arrogance, pronounced the kernel worthless, because he saw no value in the shell. The real use of travelling to distant countries and of studying the annals of past times is to preserve men from the contraction of mind which those can hardly escape whose whole communion is with one generation and one neighbourhood, who arrive at conclusions by means of an induction not sufficiently copious, and who therefore constantly confound exceptions with rules, and accidents with essential properties. In short, the real use of travelling and of studying history is to keep men from being what Tom Dawson was in fiction, and Samuel Johnson in reality."

"At that very time, while the fanatical Moslem were plundering the churches and palaces of Constantinople, breaking in pieces Grecian sculptures, and giving to the flames piles of Grecian eloquence, a few humble German artisans, who little knew that they were calling into existence a power far mightier than that of the victorious Sultan, were busied in culling and setting the first types. The University [of Glasgow] came into existence just in time to witness the disappearance of the last trace of the Roman empire, and to witness the publication of the earliest printed book."

"At the time when that odious style which deforms the writings of Hall and of Lord Bacon was almost universal, had appeared that stupendous work, the English Bible, a book which, if everything else in our language should perish, would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power. The respect which the translators felt for the original prevented them from adding any of the hideous decorations then in fashion. The ground-work of the version, indeed, was of an earlier age."

"Assuredly, if the tree which Socrates planted and Plato watered is to be judged of by its flowers and leaves, it is the noblest of trees. But if we take the homely test of Bacon, if we judge of the tree by its fruits, our opinion of it may perhaps be less favourable. When we sum up all the useful truths which we owe to that philosophy, to what do they amount? We find, indeed, abundant proofs that some of those who cultivated it were men of the first order of intellect. We find among their writings incomparable specimens both of dialectical and rhetorical art. We have no doubt that the ancient controversies were of use, in so far as they served to exercise the faculties of the disputants; for there is no controversy so idle that it may not be of use in this way. But when we look for something more, for something which adds to the comforts or alleviates the calamities of the human race, we are forced to own ourselves disappointed. We are forced to say with Bacon that this celebrated philosophy ended in nothing but disputation, that it was neither a vineyard nor an olive-ground, but an intricate wood of briers and thistles, from which those who lost themselves in it brought back many scratches and no food."

"Attend, all ye who list to hear our noble England's praise; I tell of the thrice-noble deeds she wrought in ancient days."

"Bacon fixed his eye on a mark which was placed on the earth, and within bow-shot, and hit it in the white. The philosophy of Plato began in words and ended in words,—noble words indeed, words such as were to be expected from the finest of human intellects exercising boundless dominion over the finest of human languages. The philosophy of Bacon began in observations and ended in arts."

"Bishop Watson compares a geologist to a gnat mounted on an elephant and laying down theories as to the whole internal structure of the vast animal from the phenomena of the hide. The comparison is unjust to the geologists, but is very applicable to those historians who write as if the body politic were homogeneous, who look only on the surface of affairs, and never think of the mighty and various organization which lies deep below."

"Both in individuals, and in masses, violent excitement is always followed by remission, and often by reaction. We are all inclined to depreciate what we have over-praised, and, on the other hand, to show undue indulgence where we have shown undue rigor."

"Books, however, were the least part of the education of an Athenian citizen. Let us, for a moment, transport ourselves in thought to that glorious city. Let us imagine that we are entering its gates in the time of its power and glory. A crowd is assembled round a portico. All are gazing with delight at the entablature; for Phidias is putting up the frieze. We turn into another street; a rhapsodist is reciting there: men, women, children are thronging round him: the tears are running down their cheeks: their eyes are fixed: their very breath is still; for he is telling how Priam fell at the feet of Achilles, and kissed those hands—the terrible,—the murderous—which had slain so many of his sons. We enter the public place; there is a ring of youths, all leaning forward, with sparkling eyes, and gestures of expectation. Socrates is pitted against the famous atheist from Ionia, and has just brought him to a contradiction in terms. But we are interrupted. The herald is crying, Room for the Pytanes! The general assembly is to meet. The people are swarming in on every side. Proclamation is made—Who wishes to speak? There is a shout, and a clapping of hands: Pericles is mounting the stand. Then for a play of Sophocles; and away to sup with Aspasia. I know of no modern university which has so excellent a system of education."

"Books are becoming everything to me. If I had at this moment any choice in life, I would bury myself in one of those immense libraries...and never pass a waking hour without a book before me."

"Books quite worthless are quite harmless. The sure sign of the general decline of an art is the frequent occurrence, not of deformity, but of misplaced beauty. In general, Tragedy is corrupted by eloquence, and Comedy by wit. The real object of the drama is the exhibition of human character. This, we conceive, is no arbitrary canon, originating in local and temporary associations, like those canons which regulate the number of acts in a play, or of syllables in a line. To this fundamental law every other regulation is subordinate. The situations which most signally develop character form the best plot. The mother-tongue of the passions is the best style. This principle, rightly understood, does not debar the poet from any grace of composition. There is no style in which some man may not, under some circumstances, express himself. There is, therefore, no style which the drama rejects, none which it does not occasionally require. It is in the discernment of place, of time, and of person that the inferior artists fail. The fantastic rhapsody of Mercutio, the elaborate declamation of Antony, are, where Shakespeare has placed them, natural and pleasing. But Dryden would have made Mercurio challenge Tybalt in hyperboles as fanciful as those in which he describes the chariot of Mab. Corneille would have represented Antony as scolding and coaxing Cleopatra with all the measured rhetoric of a funeral oration."

"But among the young candidates for Addison’s favour there was one distinguished by talents above the rest, and distinguished, we fear, not less by malignity and insincerity. Pope was only twenty-five. But his powers had expanded to their full maturity; and his best poem, the Rape of the Lock, had recently been published. Of his genius, Addison had always expressed high admiration. But Addison had early discerned, what might indeed have been discerned by an eye less penetrating than his, that the diminutive, crooked, sickly boy was eager to revenge himself on society for the unkindness of nature. In the Spectator, the Essay on Criticism had been praised with cordial warmth; but a gentle hint had been added, that the writer of so excellent a poem would have done well to avoid ill-natured personalities. Pope, though evidently more galled by the censure than gratified by the praise, returned thanks for the admonition, and promised to profit by it. The two writers continued to exchange civilities, counsel, and small good offices. Addison publicly extolled Pope’s miscellaneous pieces; and Pope furnished Addison with a prologue. This did not last long. Pope hated Dennis, whom he had injured without provocation. The appearance of the Remarks on Cato gave the irritable poet an opportunity of venting his malice under the show of friendship; and such an opportunity could not but be welcome to a nature which was implacable in enmity, and which always preferred the tortuous to the straight path. He published, accordingly, the Narrative of the Frenzy of John Dennis. But Pope had mistaken his powers. He was a great master of invective and sarcasm: he could dissect a character in terse and sonorous couplets, brilliant with antithesis: but of dramatic talent he was altogether destitute. If he had written a lampoon on Dennis, such as that on Atticus, or that on Sporus, the old grumbler would have been crushed. But Pope writing dialogue resembled—to borrow Horace’s imagery and his own—a wolf which, instead of biting, should take to kicking, or a monkey which should try to sting. The Narrative is utterly contemptible. Of argument there is not even the show; and the jests are such as, if they were introduced into a farce, would call forth the hisses of the shilling gallery. Dennis raves about the drama; and the nurse thinks that he is calling for a dram. There is, he cries, no peripetia in the tragedy, no change of fortune, no change at all. Pray, good sir, be not angry, says the old woman; I’ll fetch change. This is not exactly the pleasantry of Addison."

"But in truth the very admiration which we feel for the eminent philosophers of antiquity forces us to adopt the opinion that their powers were systematically misdirected. For how else could it be that such powers should effect so little for mankind? A pedestrian may show as much muscular vigour on a treadmill as on the highway road. But on the road his vigour will assuredly carry him forward; and on the treadmill he will not advance an inch. The ancient philosophy was a treadmill, not a path. It was made up of revolving questions, of controversies which were always beginning again. It was a contrivance for having much exertion and no progress. We must acknowledge that more than once, while contemplating the doctrines of the Academy and the Portico, even as they appear in the transparent splendour of Cicero’s incomparable diction, we have been tempted to mutter with the surly centurion in Persius, Cur quis non prandeat hoc est? What is the highest good, whether pain be an evil, whether all things be fated, whether we can be certain of anything, whether we can be certain that we are certain of nothing, whether a wise man can be unhappy, whether all departures from right be equally reprehensible, these, and other questions of the same sort, occupied the brains, the tongues, and the pens of the ablest men in the civilized world during several centuries. This sort of philosophy, it is evident, could not be progressive. It might indeed sharpen and invigorate the minds of those who devoted themselves to it; and so might the disputes of the orthodox Lilliputians and the heretical Blefuscudians about the big ends and the little ends of eggs. But such disputes could add nothing to the stock of knowledge. The human mind accordingly, instead of marching, merely marked time. It took as much trouble as would have sufficed to carry it forward; and yet remained on the same spot. There was no accumulation of truth, no heritage of truth acquired by the labour of one generation and bequeathed to another, to be again transmitted with large additions to a third. Where this philosophy was in the time of Cicero, there it continued to be in the time of Seneca, and there it continued to be in the time of Favorinus. The same sects were still battling with the same unsatisfactory arguments about the same interminable questions. There had been no want of ingenuity, of zeal, of industry. Every trace of intellectual cultivation was there, except a harvest. There had been plenty of ploughing, harrowing, reaping, threshing. But the garners contained only smut and stubble."

"But it was not solely or principally to outward accomplishments that Pitt owed the vast influence which, during nearly thirty years, he exercised over the House of Commons. He was undoubtedly a great orator; and, from the descriptions of his contemporaries, and the fragments of his speeches which still remain, it is not difficult to discover the nature and extent of his oratorical powers."

"But if there were a painter so gifted that he could place on the canvas that glorious paradise seen by the interior eye of him whose outward sight had failed with long watching and labouring for liberty and truth, if there were a painter who could set before us the mazes of the sapphire brook, the lake with its fringe of myrtles, the flowery meadows, the grottoes overhung by vines, the forests shining with Hesperian fruit and with the plumage of gorgeous birds, the mossy shade of that nuptial bower which showered down roses on the sleeping lovers, what should we think of a connoisseur who should tell us that this painting, though finer than the absurd picture in the old Bible, was not so correct? Surely we should answer, It is both finer and more correct; and it is finer because it is more correct. It is not made up of correctly drawn diagrams; but it is a correct painting, a worthy representation of that which it is intended to represent."

"But Dryden was, as we have said, one of those writers in whom the period of imagination does not precede, but follow, the period of observation and reflection."

"But in fact it would have been impossible, since the Revolution, to punish any Minister for the general course of his policy, with the slightest semblance of justice; for since that time no Minister has been able to pursue any general course of policy without the approbation of the Parliament."

"But Sir Nicholas was no ordinary man. He belonged to a set of men whom it is easier to describe collectively than separately, whose minds were formed by one system of discipline, who belonged to one rank in society, to one university, to one party, to one sect, to one administration, and who resembled each other so much in talents, in opinions, in habits, in fortunes, that one character, we had almost said one life, may, to a considerable extent, serve for them all."

"But narration, though an important part of the business of a historian, is not the whole. To append a moral to a work of fiction is either useless or superfluous. A fiction may give a more impressive effect to what is already known, but it can teach nothing new. If it presents to us characters and trains of events to which our experience furnishes us with nothing similar, instead of deriving instruction from it we pronounce it unnatural. We do not form our opinions from it; but we try it by our preconceived opinions. Fiction, therefore, is essentially imitative. Its merit consists in its resemblance to a model with which we are already familiar, or to which at least we can instantly refer. Hence it is that the anecdotes which interest us most strongly in authentic narrative are offensive when introduced into novels; that what is called the romantic part of history is in fact the least romantic. It is delightful as history, because it contradicts our previous notions of human nature and of the connection of causes and effects. It is on that very account shocking and incongruous in fiction. In fiction, the principles are given, to find the facts: in history, the facts are given, to find the principles; and the writer who does not explain the phenomena as well as state them, performs only one-half of his office. Facts are the mere dross of history. It is from the abstract truth which interpenetrates them, and lies latent among them like gold in the ore, that the mass derives its whole value: and the precious particles are generally combined with the baser in such a manner that the separation is a task of the utmost difficulty."

"But that which chiefly distinguishes Addison from Swift, from Voltaire, from almost all the other great masters of ridicule, is the grace, the nobleness, the moral purity, which we find even in his merriment. Severity, gradually hardening and darkening into misanthropy, characterizes the works of Swift. The nature of Voltaire was, indeed, not inhuman; but he venerated nothing. Neither in the masterpieces of art nor in the purest examples of virtue, neither in the Great First Cause nor in the awful enigma of the grave, could he see anything but subjects for drollery. The more solemn and august the theme, the more monkeylike was his grimacing and chattering. The mirth of Swift is the mirth of Mephistopheles; the mirth of Voltaire is the mirth of Puck. If, as Soame Jenyns oddly imagined, a portion of the happiness of seraphim and just men made perfect be derived from an exquisite perception of the ludicrous, their mirth must surely be none other than the mirth of Addison; a mirth consistent with tender compassion for all that is frail, and with profound reverence for all that is sublime. Nothing great, nothing amiable, no moral duty, no doctrine of natural or revealed religion, has ever been associated by Addison with any degrading idea. His humanity is without a parallel in literary history. The highest proof of virtue is to possess boundless power without abusing it. No kind of power is more formidable than the power of making men ridiculous; and that power Addison possessed in boundless measure. How grossly that power was abused by Swift and by Voltaire is well known. But of Addison it may be confidently affirmed that he has blackened no man’s character, nay, that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find in all the volumes which he has left us a single taunt which can be called ungenerous or unkind. Yet he had detractors whose malignity might have seemed to justify as terrible a revenge as that which men not superior to him in genius wreaked on Bettesworth and on Franc de Pompignan. He was a politician; he was the best writer of his party; he lived in times of fierce excitement, in times when persons of high character and station stooped to scurrility such as is now practiced only by the basest of mankind. Yet no provocation and no example could induce him to return railing for railing."

"But that which gave most effect to his declamation was the air of sincerity, of vehement feeling, of moral elevation, which belonged to all that he said. His style was not always in the purest taste. Several contemporary judges pronounced it too florid. Walpole, in the midst of the rapturous eulogy which he pronounces on one of Pitt’s greatest orations, owns that some of the metaphors were too forced. Some of Pitt’s quotations and classical stories are too trite for a clever schoolboy. But these were niceties for which the audience cared little. The enthusiasm of the orator infected all who heard him; his ardour and his noble bearing put fire into the most frigid conceit, and gave dignity to the most puerile allusion."

"But the Puritans drove imagination from its last asylum. They prohibited theatrical representations, and stigmatized the whole race of dramatists as enemies of morality and religion. Much that is objectionable may be found in the writers whom they reprobated; but whether they took the best measures for stopping the evil appears to us very doubtful, and must, we think, have appeared doubtful to themselves, when, after the lapse of a few years, they saw the unclean spirit whom they had cast out return to his old haunts, with seven others fouler than himself."

"But the hopes and fears of man are not limited to this short life, and to this visible world. He finds himself surrounded by the signs of a power and wisdom higher than his own; and in all ages and nations men of all orders of intellect, from Bacon and Newton down to the rudest tribes of cannibals, have believed in the existence of some superior mind. Thus far the voice of mankind is almost unanimous. But whether there be one God or many, what may be his natural and what his moral attributes, in what relation his creatures stand to him, whether he have ever disclosed himself to us by any other revelation than that which is written in all the parts of the glorious and well-ordered world which he has made, whether his revelation be contained in any permanent record, how that record should be interpreted, and whether it have pleased him to appoint any unerring interpreter on earth, these are questions respecting which there exists the widest diversity of opinion, and respecting which a large part of our race has, ever since the dawn of regular history, been deplorably in error. Now here are two great objects: one is the protection of the persons and estates of citizens from injury; the other is the propagation of religious truth. No two objects more entirely distinct can well be imagined. The former belongs wholly to the visible and tangible world in which we live; the latter belongs to that higher world which is beyond the reach of our senses. The former belongs to this life; the latter to that which is to come. Men who are perfectly agreed as to the importance of the former object, and as to the way of obtaining it, differ as widely as possible respecting the latter object. We must therefore pause before we admit that the persons, be they who they may, who are intrusted with power for the promotion of the former object ought always to use that power for the promotion of the latter object."

"But the very considerations which lead us to look forward with sanguine hope to the future prevent us from looking back with contempt on the past. We do not flatter ourselves with the notion that we have attained perfection, and that no more truth remains to be found. We believe that we are wiser than our ancestors. We believe, also, that our posterity will be wiser than we. It would be gross injustice in our grandchildren to talk of us with contempt, merely because they may have surpassed us; to call Watt a fool, because mechanical powers may be discovered which may supersede the use of steam; to deride the efforts which have been made in our time to improve the discipline of prisons and to enlighten the minds of the poor, because future philanthropists may devise better places of confinement than Mr. Bentham’s Panopticon, and better places of education than Mr. Lancaster’s schools. As we would have our descendants judge us, so we ought to place ourselves in their situation, to put out of our minds, for a time, all that knowledge which they, however eager in the pursuit of truth, could not have, and which we, however negligent we may have been, could not help having. It was not merely difficult, but absolutely impossible, for the best and greatest of men, two hundred years ago, to be what a very commonplace person in our days may easily be, and indeed must necessarily be. But it is too much that the benefactors of mankind, after having been reviled by the dunces of their own generation for going too far, should be reviled by the dunces of the next generation for not going far enough."

"But though his [Dr. S. Johnson’s] pen was now idle, his tongue was active. The influence exercised by his conversation, directly upon those with whom he lived, and indirectly on the whole literary world, was altogether without a parallel. His colloquial talents were indeed of the highest order. He had strong sense, quick discernment, wit, humour, immense knowledge of literature and of life, and an infinite store of curious anecdotes. As respected style, he spoke far better than he wrote. Every sentence which dropped from his lips was as correct in structure as the most nicely balanced period of the Rambler. But in his talk there were no pompous triads, and little more than a fair proportion of words in osity and ation. All was simplicity, ease, and vigour. He uttered his short, weighty, and pointed sentences with a power of voice, and a justness and energy of emphasis, of which the effect was rather increased than diminished by the rollings of his huge form, and by the asthmatic gaspings in which the peals of his eloquence generally ended. Nor did the laziness which made him unwilling to sit down to his desk prevent him from giving instruction or entertainment orally. To discuss questions of taste, of learning, of casuistry, in language so exact and so forcible that it might have been printed without the alteration of a word, was to him no exertion, but a pleasure. He loved, as he said, to fold his legs and have his talk out. He was ready to bestow the overflowings of his full mind on anybody who would start a subject,—on a fellow-passenger in a stage-coach, or on the person who sate at the same table with him in an eating-house. But his conversation was nowhere so brilliant and striking as when he was surrounded by a few friends whose abilities and knowledge enabled them, as he once expressed it, to send him back every ball that he threw."

"But there are a few characters which have stood the closest scrutiny and the severest tests, which have been tried in the furnace and have proved pure, which have been weighed in the balance and have not been found wanting, which have been declared sterling by the general consent of mankind, and which are visibly stamped with the image and superscription of the Most High. These great men we trust that we know how to prize; and of these was Milton. The sight of his books, the sound of his name, are pleasant to us. His thoughts resemble those celestial fruits and flowers which the Virgin Martyr of Massinger sent down from the gardens of Paradise to the earth, and which were distinguished from the productions of other soils, not only by superior bloom and sweetness, but by miraculous efficacy to invigorate and to heal. They are powerful, not only to delight, but to elevate and purify. Nor do we envy the man who can study either the life or the writings of the great poet and patriot, without aspiring to emulate, not indeed the sublime works with which his genius has enriched our literature, but the zeal with which he laboured for the public good, the fortitude with which he endured every private calamity, the lofty disdain with which he looked down on temptations and dangers, the deadly hatred which he bore to bigots and tyrants, and the faith which he so sternly kept with his country and with his fame."

"But what shall we say of Addison’s humour, of his sense of the ludicrous, of his power of awakening that sense in others, and of drawing mirth from incidents which occur every day, and from little peculiarities of temper and manner, such as may be found in every man? We feel the charm, we give ourselves up to it; but we strive in vain to analyze it."

"But this is not enough. Will without power, said the sagacious Casimir to Milor Beefington, is like children playing at soldiers. The people will always be desirous to promote their own interests; but it may be doubted whether, in any community, they were ever sufficiently educated to understand them. Even in this island, where the multitude have long been better informed than in any other part of Europe, the rights of the many have generally been asserted against themselves by the patriotism of the few."

"But we shall leave this abstract question, and look at the world as we find it. Does, then, the way in which governments generally obtain their power make it at all probable that they will be more favourable to orthodoxy than to heterodoxy? A nation of barbarians pours down on a rich and unwarlike empire, enslaves the people, portions out the land, and blends the institutions which it finds in the cities with those which it has brought from the woods. A handful of daring adventurers from a civilized nation wander to some savage country, and reduce the aboriginal race to bondage. A successful general turns his arms against the state which he serves. A society, made brutal by oppression, rises madly on its masters, sweeps away all old laws and usages, and, when its first paroxysm of rage is over, sinks down passively under any form of polity which may spring out of the chaos. A chief of a party, as at Florence, becomes imperceptibly a sovereign, and the founder of a dynasty. A captain of mercenaries, as at Milan, seizes on a city, and by the sword makes himself its ruler. An elective senate, as at Venice, usurps permanent and hereditary power. It is in events such as these that governments have generally originated; and we can see nothing in such events to warrant us in believing that the governments thus called into existence will be peculiarly well fitted to distinguish between religious truth and heresy."

"But where has this principle been demonstrated? We are curious, we confess, to see this demonstration which is to change the face of the world, and yet to convince nobody."

"But with Theology the case is very different. As respects natural religion,—revelation being for the present altogether left out of the question,—it is not easy to see that a philosopher of the present day is more favourably situated than Thales or Simonides. He has before him just the same evidences of design in the structure of the universe which the early Greeks had. We say just the same; for the discoveries of modern astronomers and anatomists have really added nothing to the force of that argument which a reflecting mind finds in every beast, bird, insect, fish, leaf, flower, and shell."

"But, low as was the state of our poetry during the civil war and the Protectorate, a still deeper fall was at hand. Hitherto our literature had been idiomatic. In mind, as in situation, we had been islanders. The revolutions in our taste, like the revolutions in our government, had been settled without the interference of strangers. Had this state of things continued, the same just principles of reasoning which about this time were applied with unprecedented success to every part of philosophy would soon have conducted our ancestors to a sounder code of criticism. There were already strong signs of improvement. Our prose had at length worked itself clear from those quaint conceits which still deformed almost every metrical composition. The parliamentary debates, and the diplomatic correspondence, of that eventful period had contributed much to this reform. In such bustling times it was absolutely necessary to speak and write to the purpose. The absurdities of Puritanism had, perhaps, done more. At the time when that odious style which deforms the writings of Hall and of Lord Bacon was almost universal, had appeared that stupendous work, the English Bible,—a book which if everything else in our language should perish would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power. The respect which the translators felt for the original prevented them from adding any of the hideous decorations then in fashion. The ground-work of the version, indeed, was of an earlier age. The familiarity with which the Puritans, on almost every occasion, used the Scripture phrases was no doubt very ridiculous; but it produced good effects. It was a cant; but it drove out a cant far more offensive."

"Bute, who had always been considered as a man of taste and reading, affected from the moment of his elevation the character of a Mæcenas. If he expected to conciliate the public by encouraging literature and art, he was grievously mistaken. Indeed, none of the objects of his munificence, with the single exception of Johnson, can be said to have been well selected; and the public, not unnaturally, ascribed the selection of Johnson rather to the Doctor’s political prejudices than to his literary merits: for a wretched scribbler named Shebbeare, who had nothing in common with Johnson except violent Jacobitism, and who had stood in the pillory for a libel on the Revolution, was honoured with a mark of royal approbation similar to that which was bestowed on the author of the English Dictionary and of the Vanity of Human Wishes. It was remarked that Adam, a Scotchman, was the court architect; and that Ramsay, a Scotchman, was the court painter, and was preferred to Reynolds. Mallet, a Scotchman, of no high literary fame, and of infamous character, partook largely of the liberality of the government. John Home, a Scotchman, was rewarded for the tragedy of Douglas, both with a pension and with a sinecure place. But when the author of The Bard and of the Elegy in a Country Churchyard ventured to ask for a Professorship, the emoluments of which he much needed, and for the duties of which he was, in many respects, better qualified than any man living, he was refused; and the post was bestowed on the pedagogue under whose care the favourite’s son-in-law, Sir James Lowther, had made such signal proficiency in the graces and in the humane virtues."

"By poetry we mean the art of employing of words in such a manner as to produce an illusion on the imagination; the art of doing by means of words, what the painter does by means of colors."

"By the extinction of the drama, the fashionable school of poetry—a school without truth of sentiment or harmony of versification,—without the powers of an earlier or the correctness of a later age—was left to enjoy undisputed ascendency. A vicious ingenuity, a morbid quickness to perceive resemblances and analogies between things apparently heterogeneous, constituted almost its only claim to admiration. Suckling was dead. Milton was absorbed in political and theological controversy. If Waller differed from the Cowleian sect of writers, he differed for the worse. He had as little poetry as they, and much less wit; nor is the languor of his verses less offensive than the ruggedness of theirs. In Denham alone the faint dawn of a better manner was discernible."

"Cervantes is the delight of all classes of readers. Every school-boy thumbs to pieces the most wretched translations of his romance, and knows the lantern jaws of the Knight Errant, and the broad cheeks of the Squire, as well as the faces of his own playfellows. The most experienced and fastidious judges are amazed at the perfection of that art which extracts in extinguishable laughter from the greatest of human calamities without once violating the reverence due to it; at that discriminating delicacy of touch which makes a character exquisitely ridiculous without impairing its worth, its grace, or its dignity. In Don Quixote are several dissertations on the principles of poetic and dramatic writing. No passages in the whole work exhibit stronger marks of labour and attention; and no passages in any work with which we are acquainted are more worthless and puerile. In our time they would scarcely obtain admittance into the literary department of The Morning Post."

"Chatham, at the time of his decease, had not, in both Houses of Parliament, ten personal adherents. Half of the public men of the age had been estranged from him by his errors, and the other half by the exertions which he had made to repair his errors. His last speech had been an attack at once on the policy pursued by the government and on the policy recommended by the opposition. But death restored him to his old place in the affection of his country. Who could hear unmoved of the fall of that which had been so great, and which had stood so long?… High over those venerable graves towers the stately monument of Chatham, and from above, his effigy, graven by a cunning hand, seems still, with eagle face and outstretched arm, to bid England be of good cheer, and to hurl defiance at her foes. The generation which reared that monument of him has disappeared. The time has come when the rash and indiscriminate judgments which his contemporaries passed on his character may be calmly revised by history. And history, while, for the warning of vehement, high, and daring natures, she notes his many errors, will yet deliberately pronounce that, among the eminent men whose bones lie near his, scarcely one has left a more stainless, and none a more splendid, name."

"Children, look in those eyes, listen to that dear voice, notice the feeling of even a single touch that is bestowed upon you by that gentle hand! Make much of it while yet you have that most precious of all good gifts, a loving mother. Read the unfathomable love of those eyes; the kind anxiety of that tone and look, however slight your pain. In after life you may have friends, fond, dear friends, but never will you have again the inexpressible love and gentleness lavished upon you, which none but a mother bestows."

"Charles V said that a man who knew four languages was worth four men; and Alexander the Great so valued learning, that he used to say he was more indebted to Aristotle for giving him knowledge than his father Philip for giving him life."

"Constitutions are in politics what paper money is in commerce. They afford great facilities and conveniences. But we must not attribute to them that value which really belongs to what they represent. They are not power, but symbols of power, and will, in an emergency, prove altogether useless unless the power for which they stand be forthcoming. The real power by which the community is governed is made up of all the means which all its members possess of giving pain or pleasure to each other."

"Copyright is monopoly, and produces all the effects which the general voice of mankind attributes to monopoly.. Monopoly is an evil. For the sake of the good we must submit to the evil; but the evil ought not to last a day longer than is necessary for the purpose of securing the good.[3]"

"Cowper said, forty or fifty years ago, that he dared not name John Bunyan in his verse, for fear of moving a sneer. To our refined forefathers, we suppose, Lord Roscommon’s Essay on Translated Verse, and the Duke of Buckingham’s Essay on Poetry, appeared to be compositions infinitely superior to the allegory of the preaching tinker. We live in better times; and we are not afraid to say, that, though there were many clever men in England during the latter half of the seventeenth century, there were only two minds which possessed the imaginative faculty in a very eminent degree. One of these minds produced the Paradise Lost, the other the Pilgrim’s Progress."

"Diversity, it is said, implies error: truth is one, and admits of no degrees. We answer, that this principle holds good only in abstract reasonings. When we talk of the truth of imitation in the fine arts, we mean an imperfect and a graduated truth. No picture is exactly like the original; nor is a picture good in proportion as it is like the original. When Sir Thomas Lawrence paints a handsome peeress, he does not contemplate her through a powerful microscope, and transfer to the canvas the pores of the skin, the blood-vessels of the eye, and all the other beauties which Gulliver discovered in the Brobdignaggian maids of honour. If he were to do this, the effect would be not merely unpleasant, but, unless the scale of the picture were proportionably enlarged, would be absolutely false. And, after all, a microscope of greater power than that which he employed would convict him of innumerable omissions. The same may be said of history. Perfectly and absolutely true it cannot be: for, to be perfectly and absolutely true, it ought to record all the slightest particulars of the slightest transactions,—all the things done and all the words uttered during the time of which it treats. The omission of any circumstance, however insignificant, would be a defect. If history were written thus, the Bodleian Library would not contain the occurrences of a week. What is told in the fullest and most accurate annals bears an infinitely small proportion to that which is suppressed. The difference between the copious work of Clarendon and the account of the civil wars in the abridgment of Goldsmith vanishes when compared with the immense mass of facts about which both are equally silent."