Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

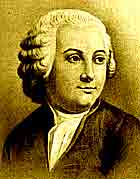

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac

French Philosopher and Epistemologist

"It is through uneasiness that all habits of mind and body are born."

"If we had no motivation to be preoccupied with our sensations, the impressions that objects made on us would pass like shadows, and leave no trace. After several years, we would be the same as we were at our first moment, without having acquired any knowledge, and without having any other faculties than feeling. But the nature of our sensations does not let us remain enslaved in this lethargy. Since they are necessarily agreeable or disagreeable, we are involved in seeking the former, avoiding the latter; and the greater the intensity of difference between pleasure and pain, the more it occasions action in our souls. Thus the privation of an object that we judge necessary for our well-being, gives us disquiet, that uneasiness we call need, and from which desires are born. These needs recur according to circumstances, often quite new ones present themselves, and it is in this way that our knowledge and faculties develop."

"Would you like to learn science? Begin by learning your own language."

"It would be of no use to inquire into the nature of our thoughts. The first reflection we make on ourselves is sufficient to convince us, that we have no possible means of satisfying this inquiry. Every man is conscious of his thought; he distinguishes it perfectly from every thing else; he even distinguishes one thought from another ; and that is sufficient. If we go any further, we stray from a point which we apprehend so clearly, that it can never lead us into error."

"The soul being distinct and different from the body, the latter can be only occasionally the cause of what it seems to produce in the former. From whence we must conclude, that the fenses are only.occasionally the source of our knowledge."

"Let us therefore conclude that there are no ideas but such as are acquired: the first proceed immediately from the senses; the others are owing to experience, and increase in proportion as we become capable of reflecting."

"The connexion of ideas can arise from no other cause, than from the attention given to them, when they presented themselves conjunctly to our minds."

"And yet it is not always in our power to revive the perceptions we have felt. On some occasions the most we can do is by recalling to mind their names, to recollect some of the circumstances atr tending them, and an abstract idea of perception; an idea which we are capable of framing every instant, because we never think without being conscious of some perception which it depends on ourselves, to render genera)."

"And yet, let the nature of these perceptions be what it will, and let them be produced as they will, if we look amongst them for the idea of extension, for instance, of a line, of an angle, and any other figure, we shall find it in that repository very clearly and distinctly."

"All men cannot connect their ideas with equal force, nor in equal number: and this is the reason why all are not equally happy in their imagination and memory."

"A single word, which depicts nothing, would not have been sufficiently expressive to have immediately succeeded the mode of speaking by action: this was a language so well proportioned to rude capacities, that it could not be supplied by articulate sounds, without accumulating expressions one upon the other."

"But as soon as a man comes to connect ideas with signs of his own choosing, we find his memory is formed."

"Further, laws and public transactions, together with everything that deserved the attention of mankind, were multiplied to such a degree, that the memory grew too weak for so heavy a burden; and human societies increased in such a manner, that the promulgation of the laws could not, without difficulty, reach the ears of every individual."

"I distinguish therefore two sorts of perceptions among those we are conscious of; some which we remember at least the moment. After others which we forget the very moment they are impressed. This distinction is founded on the experience just now given. A person highly entertained at a play shall remember perfectly the impression made on him by a very moving scene, though he may forget how he was affected by the rest of the entertainment."

"Hence arises a perception which represents them to us as distant and limited; and which consequently implies the idea of some extension."

"If we want to revive a perception which is not familiar to us, such as the taste of a fruit of which we have eaten but once, our endeavors will terminate, generally speaking, in causing a kind of concussion in the fibres of the brain and of the mouth; and the perception shall bear no resemblance to the taste of that fruit. It would be the same in regard to a melon, to a peach, or even to a fruit of which we had never tasted. The like remark may be made in respect to the other senses."

"Hence the prejudice of the ancients against separating the music from the words. Music was in regard to them, very steady what recitation is to us: by it they learnt so regulate the voice, which before that time was under no fort of direction."

"I distinguish three sorts of signs: 1. Accidental signs, or the objects which particular circumstances have connected with some of our ideas, so as to render the one proper to revive the other. 2. Natural signs, or the cries which nature has established to express the passions of joy, of fear, or of grief, 3. Instituted signs, or those which we have chosen ourselves, and bear only an arbitrary relation to our ideas."

"In vain would outward objects solicit the senses, the mind would never have any knowledge of them, if it did not perceive them. Hence the first and smallest degree of knowledge is perception."

"It frequently happens that the imagination produces even such effects within us, as might seem to proceed from present reflection. Though we may be greatly taken up with a particular idea, yet the objects which surround us, continue to solicit our senses; the perceptions they occasion, revive others with which they are connected; and these determine certain movements in our bodies."

"In forming a habit of communicating to one another this fort of ideas by actions, mankind accustomed themselves to determine them; and from that time they began to find a greater ease in connecting them with other signs."

"It is easy to distinguish two ideas absolutely simple; but in proportion as they become more complex, the difficulties increase. Then as our notions resemble each other in more respects, there is reason to fear lest we take many of them for one only, or at least that we do not distinguish them as much as we might. This frequently happens in. metaphysics and morals. The subject which we have actually in hand, is a very sensible proof of the difficulties that are to be surmounted. On these occasions we cannot be too cautious in pointing out even the minutest differences."

"Memory, as we have seen, consists only in the power of reviving the signs of our ideas, or the circumstances that attended them; a power which never takes place, except when by the analogy of the signs we have chosen, and by the order we have settled between our ideas, the objects which we want to revive are connected with some of our present wants."

"Language was a long time without having any other words than the names which had been given to sensible objects, such as these, tree, fruit, water, fire, and others, which they had more frequent occasion to mention."

"Let us consider man the first moment of his existence; his mind immediately feels different sensations; such as light, colors, pain, pleasure, motion, rest: these arc his first thoughts."

"Music must naturally have been criticized in proportion as it improved, especially if its progress was considerable and subitaneous: for then it differs most from the sounds to which our ear is accustomed. But if we begin to be used to it, then it pleases, and it is prejudice any longer to oppose it."

"Mankind did not multiply words without necessity, especially in the beginning: for they were, at no small trouble to invent and to retain them."

"Our declamatory speaking is therefore naturally less expressive than music. For I want to know what sound is best adapted to express any particular passion? In the first place, it must surely be that which imitates the natural sign of this passion; and' this is common both to declamation and music."

"Our inquiries are sometimes more difficult, in proportion as the object of them is more simple. Our very perceptions are an instance of this. What is more easy in appearance than to determine whether the soul takes notice of all those perceptions by which it is affected? Need there anything more than to reflect on one's self? Doubtless all philosophers have done it."

"Our ideas are transformed sensations."

"Our wants are all dependent upon one another, and the perceptions of them might be considered as a series of fundamental ideas, to which we. might reduce all those which make a part of our knowledge."

"Our vocal music is so greatly different from our common recitation or declamatory speaking, that the imagination is not easily imposed upon by our musical tragedies."

"The expression of the sounds in their tuneful prosody, and that which they had also in their musical recitation, must have been introductory to the impression they were to make, when separate from the human voice."

"The dissimilarity that arose between poetic style and common language, opened a middle way from which eloquence derived its origin, and from which it sometimes deviated to draw near to the style of poetry, and sometimes to resemble common conversation. From the latter it differs only as it rejects all sorts of expressions that have not a sufficient dignity, and from the former only because it is not subject to the same measure, and according to the different character of languages, it is not allowed some particular figures and phrases which are admitted in poetry. In other respects these two arts are sometimes confounded in such a manner, that it.is no longer possible to distinguish them."

"The ideas of extension are those which we revive the most easily; because the sensations from which we derive them, are such as it is impossible for us to be without, so long as we are awake. The taste and smell may not be affected."

"Rhime did not, in the fame manner as measure, figures, and metaphors, derive its origin from the first institution of languages."

"The progress of the operations, whose analysis and origin have been here explained, is obvious. At first, there is only a simple perception in the mind, which is no more than the impression it receives from external objects."

"The language of song or vocal music is not so familiar to us, as it was to the ancients'; and that of mere instrumental performance has no longer the air of novelty, which alone has so great an effect upon the imagination."

"The prosody of different languages does not deviate equally from music. In some it affects a greater, in some a lesser variety of accents, because from the variety of constitutions in people of different climates, it is impossible they should have the same sensibility."

"The very dawn of memory is sufficient to make us masters of the habit of our imagination. A single arbitrary sign is enough to enable a person to revive an idea by himself; this is vcertainly the first and smallest degree of memory, and of the command which we may acquire over the imagination."

"The sensations therefore, and the operations of the mind, are the materials of all our knowledge; materials which our reflection employs, when by compounding pounding it seeks for the relations which they contain."

"The whole tribe of philosophers have fallen into the fame error with Locke. Some of them, who pretend that every perception leaves an image in the mind, in the same manner almost as a seal leaves its impression behind it, are not to be excepted: for what is the image of a perception, which is not the perception itself? The mistake is owing to this, that for want of having sufficiently considered the matter, they have mistaken, for the very perception of the object, some circumstances, or some general idea, which revive themselves in its stead. To avoid such mistakes, I shall here distinguish the different perceptions we are capable of feeling, and examine them each in their proper order."

"There is evidence that the faculty of reflection will appear as soon as our senses begin to develop, and it is equally true that we have the use of the senses from an early age, just because at an early age we began to reflect."

"There is neither error, nor obscurity, nor confusion in what passes within us, nor in the application we make to that which is without us."

"There were two reasons why persons of any abilities, that attempted this kind of music, could not help meeting with success. The first is, that without doubt they pitched upon such pieces, as in the course of reciting, they had been accustomed to render particularly expressive; or at least they imagined some such. The second is the surprise, which this music must needs have produced by its novelty. The greater the surprise she greater the impression of the music."

"There is still another operation which arises from the connection established by the attention betwixt our ideas; this is contemplation. It consists in preserving, without any interruption, the perception, the name or the circumstances of an object which is vanished out of sight."

"These suppositions admitted; in order to recollect the familiar ideas, it would be sufficient to be capable of giving attention to some of our fundamental ideas, with which they are connected. Now this is always feasible; because, so long as we are awake, there is not an instant in which our constitution, our passions, and our situation, do not occasion some of those perceptions which I call fundamental."

"These two arts associated themselves with that of gesture, their elder sister, and known by the name of Dance. From whence there is reason to conjecture, that some kind of dance, and some kind of music and poetry, might have been observed at all times, and in all nations."

"Thus the most natural order of ideas required, that the government should precede the verb: they said, for example, fruit to want."

"To produce harmony, the cadences ought not to be placed indifferently. Sometimes the harmony ought to be suspended, and at other times it ought to terminate with a sensible pause. Consequently in a language, whose prosody is perfect, the succession of sounds should be subordinate to the fall of each period, so that the cadences shall be more or less abrupt, and the ear shall not find a final pause, till the mind be entirely satisfied."