Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

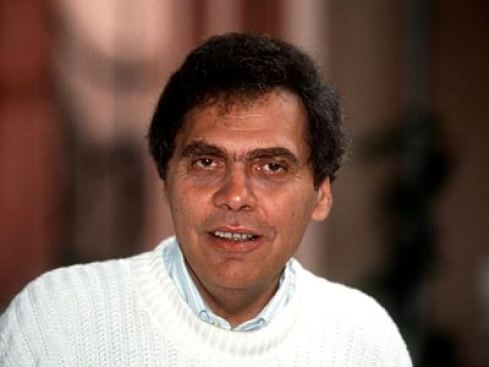

Neil Postman

American Humanist Author, Media Theorist and Cultural Critic

"The relationship between information and the mechanisms for its control is fairly simple to describe: Technology increases the available supply of information...control mechanisms are strained... When additional control mechanisms are themselves technical, they in turn further increase the supply of information. When the supply of information is no longer controllable, a general breakdown in psychic tranquility and social purpose occurs. Without defenses, people have no way of finding meaning in their experiences, lose their capacity to remember, and have difficulty imagining reasonable futures."

"The scientific method, Thomas Henry Huxley once wrote, is nothing but the normal working of the human mind. That is to say, when the mind is working; that is to say further, when it is engaged in correcting its mistakes. Taking this point of view, we may conclude that science is not physics, biology, or chemistry--is not even a subject--but a moral imperative drawn from a larger narrative whose purpose is to give perspective, balance, and humility to learning."

"The subject known variously as 'Communication,' or 'Media Studies,' or (as we call it at my university) 'Media Ecology.'... [which] takes as its domain the study of the cultural consequences of media change: how media affect our forms of social organization, our cognitive habits, and our political ideas. As a young subject, media ecology must address such fundamental questions as how to define 'media,' where to look for cultural change, and how to link changes in our media environment with changes in our ways of behaving and feeling. But such questions rest on another, larger question which is as yet unanswered -- namely, what kind of subject is this to be? Is it a science? is it a branch of philosophy? Is it a form of social criticism? Where, in short, do we place it in the catalogue? The usual, indeed the only, answer is that the subject must be a social science."

"The television commercial has mounted the most serious assault on capitalist ideology since the publication of Das Kapital. To understand why, we must remind ourselves that capitalism, like science and liberal democracy, was an outgrowth of the Enlightenment. Its principal theorists, even its most prosperous practitioners, believed capitalism to be based on the idea that both buyer and seller are sufficiently mature, well informed and reasonable to engage in transactions of mutual self-interest. If greed was taken to be the fuel of the capitalist engine, the surely rationality was the driver. The theory states, in part, that competition in the marketplace requires that the buyer not only knows what is good for him but also what is good. If the seller produces nothing of value, as determined by a rational marketplace, then he loses out. It is the assumption of rationality among buyers that spurs competitors to become winners, and winners to keep on winning. Where it is assumed that a buyer is unable to make rational decisions, laws are passed to invalidate transactions, as, for example, those which prohibit children from making contracts...Of course, the practice of capitalism has its contradictions...But television commercials make hash of it...By substituting images for claims, the pictorial commercial made emotional appeal, not tests of truth, the basis of consumer decisions. The distance between rationality and advertising is now so wide that it is difficult to remember that there once existed a connection between them. Today, on television commercials, propositions are as scarce as unattractive people. The truth or falsity of an advertiser's claim is simply not an issue. A McDonald's commercial, for example, is not a series of testable, logically ordered assertions. It is a drama--a mythology, if you will--of handsome people selling, buying and eating hamburgers, and being driven to near ecstasy by their good fortune. No claims are made, except those the viewer projects onto or infers from the drama. One can like or dislike a television commercial, of course. But one cannot refute it."

"The television commercial has mounted the most serious assault on capitalist ideology since the publication of Das Kapital."

"The terminology of a question determines the terminology of its answer."

"The title of my book was carefully chosen with a view toward its being an ambiguous prophecy [The End of Education]. As I indicated at the start, The End of Education could be taken to express a severe pessimism about the future. But if you have come this far, you will know that the book itself refuses to accept such a future. I have tried my best to locate, explain, and elaborate narratives that may give nontrivial purposes to schooling that would contribute a spiritual and serious intellectual dimension to learning. But I must acknowledge?here in my ?nal pages?that I am not terribly con?dent that any of these will work. Let me be clear on this point. I would not have troubled anyone?least of all, written a book?if I did not think these ideas have strength and usefulness. But the ideas rest on several assumptions which American culture is now beginning to question. For example, everything in the book assumes that the idea of "school" itself will endure. It also assumes that the idea of a "public school" is a good thing. And even further, it assumes that the idea of "childhood" still exists. As to the ?rst point, there is more talk than ever about schools' being nineteenth-century inventions that have outlived their usefulness. Schools are expensive; they don't do what we expect of them; their functions can be served by twenty-?rst-century technology. Anyone who wants to give a speech on this subject will draw an audience, and an attentive one. An even bigger audience can be found for a talk on the second point: that the idea of a "public school" is irrelevant in the absence of the idea of a public; that is, Americans are now so different from each other, have so many diverse points of view, and such special group grievances that there can be no common vision or unifying principles. On the last point, while writing this book, I have steadfastly refused to reread or even refer to one of my earlier books in which I claimed that childhood is disappearing. I proceeded as if this were not so. But I could not prevent myself from being exposed to other gloomy news, mostly the handwriting on the wall. Can it be true, as I read in The New York Times, that every day 130,000 children bring deadly weapons to school, and not only in New York, Chicago, and Detroit but in many venues thought to provide our young with a more settled and humane environment in which to grow? Can it be true, as some sociologists claim, that by the start of the twenty-?rst century, close to 60 percent of our children will be raised in single-parent homes? Can it be true that sexual activity (and sexual diseases) among the young has increased by 300 percent in the last twenty years? It is probably not necessary for me to go on with the "can it be true's?" Everyone agrees and all signs point to the fact that American culture is not presently organized to promote the idea of childhood; and without that idea schooling loses much of its point. These are realistic worries and must raise serious doubts for anyone who wishes to say something about schooling. Nonetheless, I offer this book in good faith, if not as much con?dence as one would wish. My faith is that school will endure since no one has invented a better way to introduce the young to the world of learning; that the public school will endure since no one has invented a better way to create a public; and that childhood will survive because without it we must lose our sense of what it means to be an adult."

"The way to be liberated from the constraining effects of any medium is to develop a perspective on it ? how it works and what it does. Being illiterate in the processes of any medium (language) leaves one at the mercy of those who control it. The new media ? these new languages ? then are among the most important "subjects" to be studied in the interests of survival. But they must be studied in a new way if they are to be understood, they must be studied as mediators of perception. Indeed, for any "subject" or "discipline" to be understood it must be studied this way."

"The world in which we live is very nearly incomprehensible to most of us. There is almost no fact... that will surprise us for very long, since we have no comprehensive and consistent picture of the world which would make the fact appear as an unacceptable contradiction...in a world without spiritual or intellectual order, nothing is unbelievable; nothing is predictable, and therefore, nothing comes as a particular surprise...The medieval world was... not without a sense of order. Ordinary men and women... had no doubt that there was such a design, and their priests were well able, by deduction from a handful of principles, to make it, if not rational, at least coherent...The situation we are presently in is much different...sadder and more confusing and certainly more mysterious...There is no consistent, integrated conception of the world which serves as the foundation on which our edifice of belief rests. And therefore... we are more naive than those of the Middle Ages, and more frightened, for we can be made to believe almost anything."

"The written word endures, the spoken word disappears."

"There are many books that are mechanically faultless but which contain untrue, unclear, or even nonsensical ideas. Carefully edited writing tells us, not that the writer speaks truly, but that he or she grasps ... the manner in which knowledge is usually expressed."

"There are two levels of knowing a subject. There is the student who knows what the definition of a noun or a gene or a molecule is; then there is the student... who also knows how the definition was arrived at. There is the student who can answer a question; then there is the student who also knows what are the biases of the question. There is the student who can give you the facts; then there is the student who also knows what is meant by a fact. I am maintaining that, in all cases, it is the latter who has a "basic" education ; the former, a frivolous one."

"There is a rhetoric of knowledge, a characteristic way in which arguments, proofs, speculations, experiments, polemics, even humor are expressed... speaking or writing a subject is a performing art, and each subject requires a somewhat different kind of performance from every other. Historians, for example, do not speak or write history in the same way biologists speak or write biology... it is worth remembering that some scholars-one thinks of Veblen in sociology, Freud in psychology, Galbraith in economics - have exerted influence as much through their manner as their matter. The point is that knowledge is a form of literature, and the various styles of knowledge ought to be studied and discussed."

"There is no escaping from ourselves. The human dilemma is as it has always been, and we solve nothing fundamental by cloaking ourselves in technological glory."

"There is nothing wrong with entertainment. As some psychiatrist once put it, we all build castles in the air. The problems come when we try to live in them. The communications media of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with telegraphy and photography at their center, called the peek-a-boo world into existence, but we did not come to live there until television. Television gave the epistemological biases of the telegraph and the photograph their most potent expression, raising the interplay of image and instancy to an exquisite and dangerous perfection. And it brought them into the home. We are by now well into a second generation of children for whom television has been their first and most accessible teacher and, for many, their most reliable companion and friend. To put it plainly, television is the command center of the new epistemology. There is no audience so young that it is barred from television. There is no poverty so abject that it must forgo television. There is no education so exalted that it is not modified by television. And most important of all, there is no subject of public interest?politics, news, education, religion, science, sports?that does not find its way to television. Which means that all public understanding of these subjects is shaped by the biases of television."

"These include the beliefs that the primary, if not the only, goal of human labor and thought is efficiency; that technical calculation is in all respects superior to human judgment; that in fact human judgment cannot be trusted, because it is plagued by laxity, ambiguity, and unnecessary complexity; that subjectivity is an obstacle to clear thinking; that what cannot be measured either does not exist or is of no value; and that the affairs of citizens are best guided and conducted by experts."

"These questions are not intended to represent a catechism for the new education. These are samples and illustrations of the kind of questions we think worth answering. Our set of questions is best regarded as a metaphor of our sense of relevance. If you took the trouble to list your own questions, it is quite possible that you prefer many or them to ours. Good enough. The new education is a process and will not suffer from the applied imaginations of all who wish to be a part of it. But in evaluating your own questions, as well as ours, bear in mind that there are certain standards that must be used. These standards must also be stated in the form of questions: [1] Will your questions increase the learner's will as well as capacity to learn? Will they help to give him a sense of joy in learning? Will they help to provide the learner with confidence in his ability to learn? [2] In order to get answers, will the learner be required to make inquiries? (Ask further questions, clarify terms, make observations, classify data, etc.?) [3] Does each question allow for alternative answers (which implies alternative modes of inquiry)? [4] Will the process of answering the questions tend to stress the uniqueness of the learner? [6] Would the answers help the learner to sense and understand the universals in the human condition and so enhance his ability to draw closer to other people?"

"They will give us artificial intelligence, and tell us that this is the way to self-knowledge... instantaneous global communication... the way to mutual understanding... Virtual Reality... the answer to spiritual poverty. But that is only the way of the technician, the fact-mongerer, the information junkie, and the technological idiot."

"Think of it all for a moment: How strange are the forms in which information is created and reality abstracted -- in sounds, scribbles, dots, pictures, electronic impulses. And what materials they require -- paper of variable textures, ink, screens, lights, punches, discs. And how much of it we may get and in what sequences. And think especially of what is required of our brains, senses, and bodies to get it. We must sit in dark places or well-lit living rooms. Light may come from behind a screen or in front of it. Pictures intersect sentences. We must go back in time or ahead of it. Or time may be suspended, contracted, or expanded. And think of how slowly some forms of information move and how rapidly do others. And think of where these forms come from and to whom they are addressed. Surely it is not too much to say that the configuration of all these properties of information has the deepest physiological, psychological, and social consequences. Nor is it too much to say -- in fact, it is saying the same thing -- that the configuration of these properties at any given time and place comprises an invisible environment around which we form our ideas about time and space, learning, knowledge, and social relations."

"This is the lesson of all great television commercials: They provide a slogan, a symbol or a focus that creates for viewers a comprehensive and compelling image of themselves. In the shift from party politics to television politics, the same goal is sought. We are not permitted to know who is best at being President or Governor or Senator, but whose image is best in touching and soothing the deep reaches of our discontent. We look at the television screen and ask, in the same voracious way as the Queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest one of all? We are inclined to vote for those whose personality, family life, and style, as imaged on the screen, give back a better answer than the Queen received. As Xenophanes remarked twenty-five centuries ago, men always make their gods in their own image. But to this, television politics has added a new wrinkle: Those who would be gods refashion themselves into images the viewers would have them be."

"Through the computer, the heralds say, we will make education better, religion better, politics better, our minds better ? best of all, ourselves better. This is, of course, nonsense, and only the young or the ignorant or the foolish could believe it."

"TV serves us most usefully when presenting junk-entertainment; it serves us most ill when it co-opts serious modes of discourse - news, politics, science, education, commerce, religion."

"To engage the written word means to follow a line of thought, which requires considerable powers of classifying, inference-making and reasoning. It means to uncover lies, confusions, and overgeneralizations, to detect abuses of logic and common sense. It also means to weigh ideas, to compare and contrast assertions, to connect one generalization to another. To accomplish this, one must achieve a certain distance from the words themselves, which is, in fact, encouraged by the isolated and impersonal text. That is why a good reader does not cheer an apt sentence or pause to applaud even an inspired paragraph. Analytic thought is too busy for that, and too detached."

"To every Old World belief, habit, or tradition, there was and still is a technological alternative. To prayer, the alternative is penicillin; to family roots, the alternative is mobility; to reading, the alternative is television; to restraint, the alternative is immediate gratification; to sin, the alternative is psychotherapy; to political ideology, the alternative is popular appeal established through scientific polling. There is even an alternative to the painful riddle of death, as Freud called it. The riddle may be postponed through longer life, and then perhaps solved altogether by cryogenics."

"Two opposing world-views ? the technological and the traditional ? coexisted in uneasy tension. The technological was the stronger, of course, but the traditional was there ? still functional, still exerting influence... This is what we find documented not only in Mark Twain but in the poetry of Walt Whitman, the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, the prose of Thoreau, the philosophy of Emerson, the novels of Hawthorne and Melville, and, most vividly of all, in Alexis de Tocqueville's monumental Democracy in America. In a word, two distinct thought-worlds were rubbing against each other in nineteenth-century America."

"Typography fostered the modern idea of individuality, but it destroyed the medieval sense of community and integration"

"Unforeseen consequences stand in the way of all those who think they see clearly the direction in which a new technology will take us. Not even those who invent a technology can be assumed to be reliable prophets... Gutenberg, for example, was by all accounts a devout Catholic who would have been horrified to hear that accursed heretic Luther describe printing as 'God's highest act of grace, whereby the business of the Gospel is driven forward.' Luther understood, as Gutenberg did not, that the mass-produced book, by placing the Word of God on every kitchen table, makes each Christian his own theologian -- one might even say his own priest, or better, from Luther's point of view, his own pope. In the struggle between unity and diversity of religious belief, the press favored the latter, and we can assume that this possibility never occurred to Gutenberg."

"Voting, we might even say, is the next to last refuge of the politically impotent. The last refuge is, of course, giving your opinion to a pollster, who will get a version of it through a desiccated question, and then will submerge it in a Niagara of similar opinions, and convert them into--what else?--another piece of news. Thus we have here a great loop of impotence: The news elicits from you a variety of opinions about which you can do nothing except to offer them as more news, about which you can do nothing."

"We are all, as Huxley says someplace, Great Abbreviators, meaning that none of us has the wit to know the whole truth, the time to tell it if we believed we did, or an audience so gullible as to accept it."

"We can imagine that Thamus [or Amun: this is a reference to a discussion on the value of writing in Plato's Phaedrus] would also have pointed out to Gutenberg, as he did to Theuth, that the new invention would create a vast population of readers who "will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction... with the conceit of wisdom instead of real wisdom"; that reading, in other words, will compete with older forms of learning. This is yet another principle of technological change we may infer from the judgment of Thamus: new technologies compete with old ones ? for time, for attention, for money, for prestige, but mostly for dominance of their world-view. This competition is implicit once we acknowledge that the medium contains an ideological bias. And it is a fierce competition, as only ideological competitions can be. It is not merely a matter of tool against tool ? the alphabet attacking ideographic writing, the printing press attacking the illuminated manuscript, the photograph attacking the art of painting, television attacking the printed word. When media make war against each other, it is a case of world-views in collision."

"We can justify the list we will submit on several grounds. First, many of these questions have literally been asked by children and adolescents when they are permitted to respond freely to the challenge of "What's Worth Knowing?" Second, some of these questions are based on careful listening to students, even though they were not at the time asking questions. Very often children make declarative statements about things when they really mean only to elicit an informative response. In some cases, they do this because they have learned from adults that it is "better" to pretend that you know than to admit that you don't. (An old aphorism describing this process goes: Children enter school as question marks and leave as periods.) In other cases they do this because they do not know how to ask certain kinds of questions. In any event, a simple translation of their declarative utterances will sometimes produce a great variety of deeply felt questions."

"We come astonishingly close to the mystical beliefs of Pythagoras and his followers who attempted to submit all of life to the sovereignty of numbers. Many of our psychologists, sociologists, economists and other latter-day cabalists will have numbers to tell them the truth or they will have nothing? We must remember that Galileo merely said that the language of nature is written in mathematics. He did not say that everything is. And even the truth about nature need not be expressed in mathematics. For most of human history, the language of nature has been the language of myth and ritual. These forms, one might add, had the virtues of leaving nature unthreatened and of encouraging the belief that human beings are part of it. It hardly befits a people who stand ready to blow up the planet to praise themselves too vigorously for having found the true way to talk about nature."

"We do not know nearly as much as we should about how children learn language, but if there is one thing we can say with assurance it is that knowledge of grammatical nomenclature and skill in sentence-parsing have no bearing whatsoever on the process."

"We have framed... some questions which in our judgment are responsive to the actual and immediate as against the fancied and future needs of learners in the world as it is (not as it was)... There seemed to be little doubt that, from the point of view of the students, these questions made much more sense than the ones they usually have to memorize the right answers to in school. Contrary to conventional school practice, what that means is that we want to elicit from the students the meanings that they have already stored up so that they may subject these meanings to a testing and verifying, reordering and reclassifying, modifying and extending process. In this process the student is not a passive "recipient"; he becomes an active producer of knowledge. The word "educate" is closely related to the word "educe." In the oldest pedagogic sense of the term, this meant a drawing out of a person something potential or latent. We can after all, learn only in relation to what we already know. Again, contrary to common misconceptions, this means that, if we don't know very much, our capability for learning is not very great. This idea ? virtually by itself ? requires a major revision in most of the metaphors that shape school policies and procedures."

"We may say then that the contribution of the telegraph to public discourse was to dignify irrelevance and amplify impotence. But this was not all: Telegraphy also made public discourse essentially incoherent. It brought into being a world of broken time and broken attention, to use Lewis Mumford's phrase. The principle strength of the telegraph was its capacity to move information, not collect it, explain it or analyze it. In this respect, telegraphy was the exact opposite of typography."

"We might say that a technology is to a medium as the brain to the mind. Like the brain, a technology is a physical apparatus. Like the mind, a medium is a use to which a physical apparatus is put. A technology becomes a medium as it employs a particular symbolic code, as it finds its place in a particular social setting, as it insinuates itself into economic and political contexts. A technology, in other words, is merely a machine. A medium is the social and intellectual environment a machine creates."

"We no longer have a coherent conception of ourselves, and our universe, and our relation to one another and our world. We no longer know, as the Middle Ages did, where we come from, and where we are going, or why. That is, we don't know what information is relevant, and what information is irrelevant to our lives."

"We rarely talk about television, only about what?s on television."

"We use language to create the world?we go where it leads. We see the world as it permits us to see it."

"What are legitimate forms of research in the social sciences? And, what are the purposes of conducting such research?... As I understand it, science is the quest to find the immutable and universal laws that govern processes, and does so on the assumption that there are cause-and-effect relations among these processes... I believe the quest to understand human behavior and feeling can in no sense except the most trivial be called science. The trivial-minded point, of course, to the fact that students of natural law and human behavior both often quantify their observations, and on this common ground may be classified together... The scientist uses mathematics to assist in uncovering and describing the structure of nature. At best, the sociologist (to take one example) uses quantification merely to give some precision to his ideas. But there is nothing especially scientific in that. All sorts of people count things in order to achieve precision without claiming that they are scientists... Just as counting things does not a scientist make, neither does observing things, though it is sometimes said that if one is empirical, one is scientific. To be empirical means to look at things before drawing conclusions. Everyone, therefore, is an empiricist, with the possible exception of paranoid schizophrenics. To be empirical also means to offer evidence that others can see as clearly as you. You may, for example, conclude that I like to write essays, offering as evidence that I have written this one and that there are several others contained in this book. You may also offer as evidence a tape recording, which I will gladly supply, on which I tell you that I like to write essays. Such evidence may be said to be empirical, and your conclusion empirically based. But your are not therefore acting as a scientist. You are acting as a rational person, to which condition many people who are not scientists may make a just claim... I believe it is important to distinguish science from non-science. There are three reasons why. First, it is always worthwhile to insist that people explain the words they have chosen to describe what they are doing, so that their purposes may be evaluated. Second, many people who use the word 'science' do so in the hope that its prestige will attach to their work... And third, when the study of human conduct is classified as science, there is a tendency to limit the kinds of inquiries that may be made: counters and 'empiricists' -- that is, pseudo-scientists -- are apt to deprive others of the right to proceed in alternative ways, for example, by denying them tenure. The result is, of course, that they impoverish all of us and make it difficult for people with ideas to be heard...Which leads me to say, at last ... what sort of work all of us who study human behavior and situations are engaged in. I will start by making reference to a famous correspondence between Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein. Freud once sent a copy of one of his books to Einstein, asking for his evaluation of it. Einstein replied that he thought the book exemplary but was not qualified to judge its scientific merit. To which Freud replied somewhat testily that if Einstein could say nothing of its scientific merit, he could not imagine how the book could be judged exemplary; it is science or it is nothing. Well, of course, Freud was wrong. His work is exemplary -- indeed, monumental -- but scarcely anyone believes today that Freud was doing science, any more than educated people believe that Marx was doing science, or Max Weber or Lewis Mumford or Bruno Bettelheim or Carl Jung or Margaret Mead or Arnold Toynbee. What these people were doing ... is weaving narratives about human behavior. Their work is a form of storytelling, not unlike conventional imaginative literature although different from it in several important ways. I call the work these people do storytelling because this suggests that an author has given a unique interpretation to a set of human events, that he has supported his interpretation with examples in various forms, and that his interpretation cannot be proved or disproved but draws its appeal from the power of its language, the depth of its explanations, the relevance of its examples, and the credibility of its theme. And that all of this has an identifiable moral purpose. The words 'true and 'false' do not apply here in the sense that they are used in mathematics or science. For there is nothing universally and irrevocably true or false about these interpretations. There are no critical tests to confirm or falsify them. There are no postulates in which they are embedded. They are bound by time, by situation, and above all by the cultural prejudices of the researcher. Quite like a piece of fiction..."

"What can be called "consciousness of the process of abstraction." That is, consciousness of the fact that out of a virtually infinite universe of possible things to pay attention to, we abstract only certain portions, and those portions turn out to be the ones for which we have verbal labels and categories. What we abstract, i.e., "see," and how we abstract it, or see it, or see it or think about it, is for all practical purposes inseparable from how we talk about it."

"What causes us the most misery and pain... has nothing to do with the sort of information made accessible by computers. The computer and its information cannot answer any of the fundamental questions we need to address to make our lives more meaningful and humane. The computer cannot provide an organizing moral framework. It cannot tell us what questions are worth asking. It cannot provide a means of understanding why we are here or why we fight each other or why decency eludes us so often, especially when we need it the most. The computer is... a magnificent toy that distracts us from facing what we most need to confront ? spiritual emptiness, knowledge of ourselves, usable conceptions of the past and future."

"What Huxley teaches is that in the age of advanced technology, spiritual devastation is more likely to come from an enemy with a smiling face than from one whose countenance exudes suspicion and hate. In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours. There is no need for wardens or gates or Ministries of Truth. When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; a culture-death is a clear possibility."

"What is information? Or more precisely, what ARE information? What are its various forms? What conceptions of intelligence, wisdom and learning does each form insist upon? What conceptions does each form neglect or mock? What are the main psychic effects of each form?... Is there a moral bias to each information form?... What redefinitions of important cultural meanings do new sources, speeds, contexts and forms of information require?... How do different forms of information persuade?... How do different information forms dictate the type of content that is expressed?"

"What is the necessary business of the schools? To create eager consumers? To transmit the dead ideas, values, metaphors, and information of three minutes ago? To create smoothly funtioning bureaucrats? These aims are truly subversive since they undermine our chances of surviving as a viable, democratic society. And they do their work in the name of convention and standard practice. We would like to see the schools go into the anti-entropy business. Now, that is subversive, too. But the purpose is to subvert attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions that foster chaos and uselessness."

"What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions". In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us."

"What the advertiser needs to know is not what is right about the product but what is wrong about the buyer."

"What we are confronted with now is the problem posed by the economic and symbolic structure of television. Those who run television do not limit our access to information but in fact widen it. Our Ministry of Culture is Huxleyan, not Orwellian. It does everything possible to encourage us to watch continuously. But what we watch is a medium which presents information in a form that renders it simplistic, non-substantive, non-historical and non-contextual; that is to say, information packaged as entertainment. In America, we are never denied the opportunity to entertain ourselves."

"What?s wrong with turning back the clock if the clock is wrong? We need not be slaves to our technologies"

"When two human beings get together, they're co-present, there is built into it a certain responsibility we have for each other, and when people are co-present in family relationships and other relationships, that responsibility is there. You can't just turn off a person. On the Internet, you can."