Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

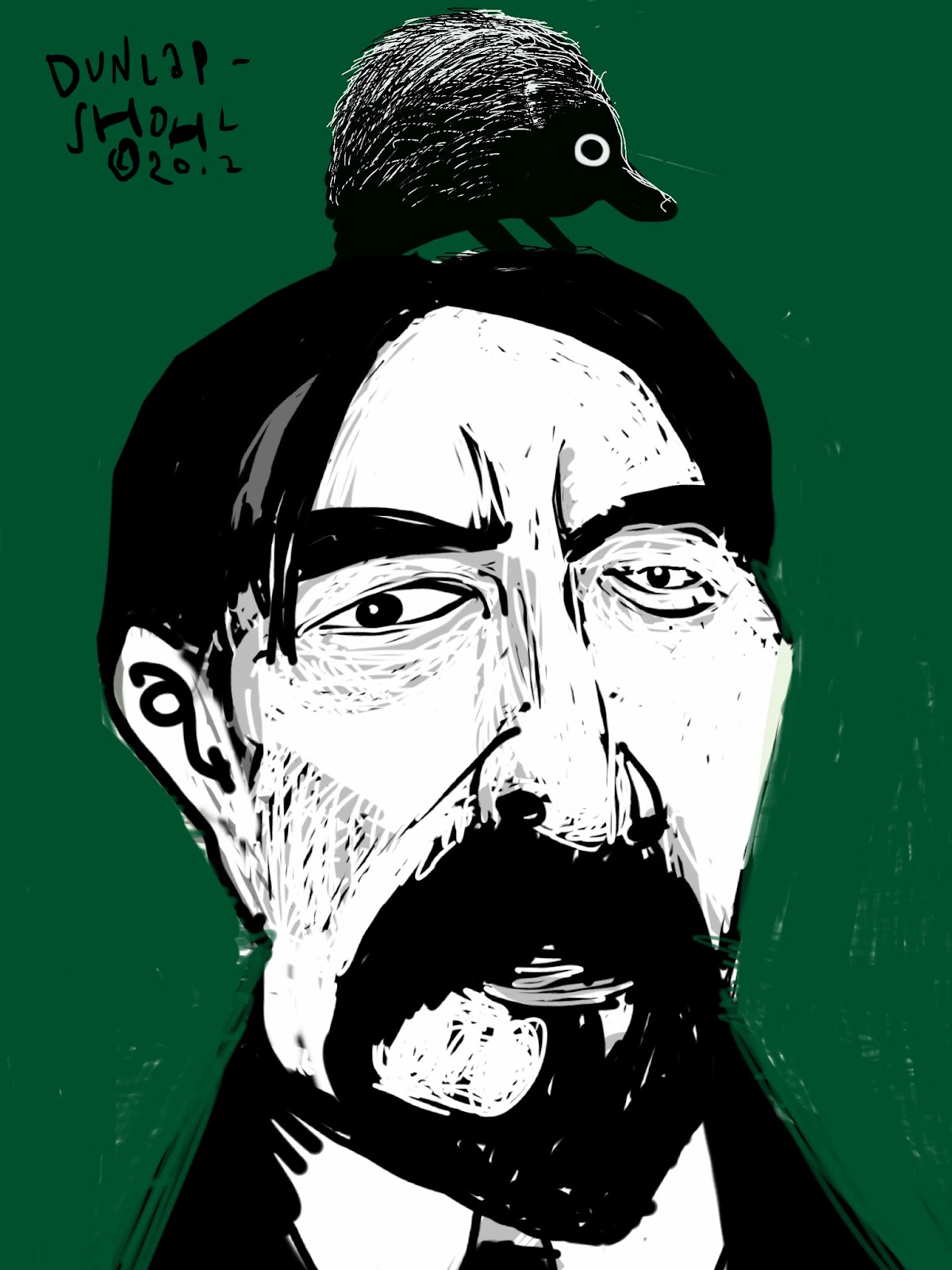

Thorstein Veblen, fully Thorstein Bunde Veblen, born Torsten Bunde Veblen

Norwegian-American Sociologist and Economist, Leader of the Institutional Economics Movement

"They are apparently moved by a feeling that so long as the established arrangements are maintained they will come in for a little something over and above what would come to them if they were to make common cause with the undistinguished common lot. In other words, they have a vested interest in a narrow margin of preference over and above what goes to the common man. But this narrow margin of net gain over the common lot, this vested right to get a narrow margin of something for nothing, has hitherto been sufficient to shape their sentiments and outlook in such a way as, in effect, to keep them loyal to the large business interests with whom they negotiate for this narrow margin of preference."

"Things have changed in such a way since that time, that the ownership of property in large holdings now controls the nation's industry, and therefore it controls the conditions of life for those who are or wish to be engaged in industry; at the same time that the same ownership of large wealth controls the markets and thereby controls the conditions of life for those who have to resort to the markets to sell or to buy. In other words, it has come to pass with the change of circumstances that the rule of Live and Let Live now waits on the discretion of the owners of large wealth. In fact, those thoughtful men in the eighteenth century who made so much of these constituent principles of the modern point of view did not contemplate anything like the system of large wealth, large-scale industry, and large-scale commerce and credit which prevails today. They did not foresee the new order in industry and business, and the system of rights and obligations which they installed, therefore, made no provision for the new order of things that has come on since their time."

"This conservatism of the wealthy class is so obvious a feature that it has even come to be recognized as a mark of respectability...it has acquired a certain honorific or decorative value. It has become prescriptive to such an extent that an adherence to conservative views is comprised as a matter of course in our notions of respectability; and it is imperatively incumbent on all who would lead a blameless life in point of social repute."

"This conspicuous leisure of which decorum is a ramification grows gradually into a laborious drill in deportment and an education in taste and discrimination as to what articles of consumption are decorous and what are the decorous methods of consuming them."

"This eighteenth-century order of nature, in the magic name of which Adam Smith was in the habit of speaking, was conceived on lines of personal initiative and activity. It is an order of things in which men were conceived to be effectually equal in all those respects that are of any decided consequence, -- in intelligence, working capacity, initiative, opportunity, and personal worth; in which the creative factor engaged in industry was the workman, with his personal skill, dexterity and judgment; in which, it was believed, the employer ("master") served his own ends and sought his own gain by consistently serving the needs of creative labor, and thereby serving the common good; in which the traders ("middle-men") made an honest living by supplying goods to consumers at a price determined by labor cost, and so serving the common good."

"this free income which the community allows its kept classes in the way of returns on these vested rights and intangible assets is the price which the community is paying to the owners of this imponderable wealth for material damage greatly exceeding that amount. But it should be kept in mind and should be duly credited to the good intentions of these businesslike managers, that the ulterior object sought by all this management is not the 100 per cent of mischief to the community but only the 10 per cent of private gain for themselves and their clients."

"This... outline of the development and nature of domestic service comes nearest being true for that cultural stage which has here been named the "quasi-peaceable" stage of industry...the quasi-peaceable stage follows the predatory stage proper, the two being successive phases of barbarian life...life at this stage still has too much of coercion and class antagonism to be called peaceable in the full sense of the word...it might as well be named the stage of status...But as a descriptive term to characterize the prevailing methods of industry, as well as... the trend of industrial development... the term "quasi-peaceable" seems preferable."

"Those persons (adult) are but a vanishing minority today who harbor no inclination to the accomplishment of some end, or who are not impelled of their own motion to shape some object or fact or relation for human use. The propensity may in large measure be overborne by the more immediately constraining incentive to a reputable leisure and an avoidance of indecorous usefulness, and it may therefore work itself out in make-believe only; as for instance in "social duties," and in quasi-artistic or quasi-scholarly accomplishments, in the care and decoration of the house, in sewing-circle activity or dress reform, in proficiency at dress, cards, yachting, golf, and various sports."

"Throughout the entire evolution of conspicuous expenditure, whether of goods or of services or human life, runs the obvious implication that in order to effectually mend the consumer's good fame it must be an expenditure of superfluities. In order to be reputable it must be wasteful. No merit would accrue from the consumption of the bare necessaries of life, except by comparison with the abjectly poor who fall short even of the subsistence minimum."

"To come to an understanding of the source and origin of this margin of disposable revenue that goes to the earnings of corporate capital, it is necessary to come to an understanding of the industrial system out of which the disposable margin of revenue arises. Productive industry yields a margin of net product over cost, counting cost in terms of man power and material resources; and under the established rule of self-help and free bargaining as it works out in corporation finance, this margin of net product has come to rest upon productive industry as an overhead charge payable to anonymous outsiders who own the corporation securities."

"To the common man who has taken to reckoning in terms of tangible performance, in terms of man power and material resources, these returns on investment that rest on productive enterprise as an overhead charge are beginning to look like unearned income. Indeed, the same unsympathetic preconception has lately come in for a degree of official recognition. High officials who are presumed to speak with authority, discretion and an unbiased mind have lately spoken of incomes from investments as "unearned incomes," and have even entertained a project for subjecting such incomes to a differential rate of taxation above what should fairly be imposed on "earned incomes," All this may, of course, be nothing more than an unseasonable lapse of circumspection on the part of the officials, who have otherwise, on the whole, consistently lived up to the best traditions of commercial sagacity; and a safe and sane legislature has also canvassed the matter and solemnly disallowed any such invidious distinction between earned and unearned incomes. Still, this passing recognition of unearned incomes is scarcely less significant for being unguarded; and the occurrence lends a certain timeliness to any inquiry into the source and nature of that net product of industry out of which any fixed overhead charges of this kind are drawn."

"To the spokesmen of "business as usual" this rating of current production under the pressure of war needs may seem extravagantly low; whereas, to the experts in industrial engineering, who are in the habit of arguing in terms of material cost and mechanical output, it will seem extravagantly high. Publicly, and concessively, this latter class will speak of a 25 percent efficiency; in private and confidentially they appear disposed to say that the rating should be nearer to 10 percent than 25. To avoid any appearance of an ungenerous bias, then, present actual production in these essential industries may be placed at something approaching 50 percent of what should be their normal productive capacity in the absence of a businesslike control looking to "reasonable profits." It is necessary at this point to call to mind that the state of the industrial arts under the new order is highly productive, -- beyond example."

"To this "natural" plan of free workmanship and free trade all restraint or retardation by collusion among business men was wholly obnoxious, and all collusive control of industry or of the market was accordingly execrated as unnatural and subversive. It is true, there were even then some appreciable beginnings of coercion and retardation -- lowering of wages and limitation of output -- by collusion between owners and employers who should by nature have been competitive producers of an unrestrained output of goods and services according to the principles of that modern point of view which animated Adam Smith and his generation; but coercion and unearned gain by a combination of ownership, of the now familiar corporate type, was virtually unknown in his time. So Adam Smith saw and denounced the dangers of unfair combination between "masters" for the exploitation of their workmen, but the modern use of credit and corporation finance for the collective control of the labor market and the goods market of course does not come within his horizon and does not engage his attention."

"Today (October, 1918) -- it is to be admitted with such emotion as may come to hand -- this question is one which can be entertained quite seriously, in the light of experience. In the recent past, as matters have stood up to the outbreak of the war, the ordinary rate of production in the essential industries under businesslike management has habitually and by deliberate contrivance fallen greatly short of productive capacity. This is an article of information which the experience of the war has shifted from the rubric of "Interesting if True" to that of "Common Notoriety.""

"Trained service has utility, not only as gratifying the master's instinctive liking for good and skillful workmanship and his propensity for conspicuous dominance over those whose lives are subservient to his own, but it has utility also as putting in evidence a much larger consumption of human service than would be shown by the mere present conspicuous leisure performed by an untrained person."

"Under the altered conditions of population, skill, and knowledge, the facility of life as carried on according to the traditional scheme may not be lower than under the earlier conditions; but the chances are always that it is less than might be if the scheme were altered to suit the altered conditions."

"Under the circumstances prevailing at any given time this [leisure] class is in a privileged position, and any departure from the existing order may be expected to work to the detriment of the class rather than the reverse. The attitude of the class... should therefore be to let well-enough alone. This interested motive comes in to supplement the strong instinctive bias of the class, and so to render it even more consistently conservative than it otherwise would be."

"Under the new order of things the mechanical equipment ? the "industrial plant" -- takes the initiative, sets the pace, and turns the workman to account in the carrying-on of those standardized processes of production that embody this mechanistic state of the industrial arts; very much as the individual craftsman in his time held the initiative in industry, set the pace, and made use of his tools according to his own discretion in the exercise of his personal skill, dexterity and judgment, under that now obsolescent industrial order which underlies the eighteenth-century modern point of view, and which still colors the aspirations of Liberal statesmen and economists, as well as the standard economic theories. The workman -- and indeed it is still the skilled workman -- is always indispensable to the due working of this mechanistic industrial process, of course; very much as the craftsman's tools, in his time, were indispensable to the work which he had in hand. But the unit of industrial organization and procedure, what may be called the "going concern" in production, is now the outfit of industrial equipment, a works, engaged in a given standardized mechanical process designed to turn out a given output of standardized product; it is the plant, or the shop."

"Under the new order the going concern in production is the plant or shop, the works, not the individual workman."

"Under the regime of emulation the members of a modern industrial community are rivals, each of whom will best attain his individual and immediate advantage if, through an exceptional exemption from scruple, he is able serenely to overreach and injure his fellows when the chance offers."

"Under this common-sense barbarian appreciation of worth or honor, the taking of life?the killing of formidable competitors, whether brute or human?is honorable in the highest degree. And this high office of slaughter... casts a glamor of worth over every act of slaughter and over all the tools and accessories of the act. Arms are honorable, and the use of them... becomes a honorific employment. At the same time, employment in industry becomes correspondingly odious, and, in the common-sense apprehension, the handling of the tools and implements of industry falls beneath the dignity of able-bodied men. Labor becomes irksome."

"Unrestricted ownership of property, with inheritance, free contract, and self-help, is believed to have been highly expedient as well as eminently equitable under the circumstances which conditioned civilized life at the period when the civilized world made up its mind to that effect. And the discrepancy which has come in evidence in this later time is traceable to the fact that other things have not remained the same. The odious outcome has been made by disturbing causes, not by these enlightened principles of honest living. Security and unlimited discretion in the rights of ownership were once rightly made much of as a simple and obvious safeguard of self-direction and self-help for the common man; whereas, in the event, under a new order of circumstances, it all promises to be nothing better than a means of assured defeat and vexation for the common man."

"Vicarious consumption practiced by the household of the middle and lower classes cannot be counted as a direct expression of the leisure-class scheme of life... The leisure class stands at the head of the social structure in point of reputability; and its manner of life and its standards of worth therefore afford the norm of reputability for the community."

"Virtually the whole range of industrial employments is an outgrowth of what is classed as woman's work in the primitive barbarian community."

"We are yet so little removed from a state of effective slavery as still to be fully sensitive to the sting of any imputation of servility. This antipathy asserts itself even in the case of the liveries or uniforms which some corporations prescribe as the distinctive dress of their employees. In this country the aversion even goes the length of discrediting?in a mild and uncertain way?those government employments, military and civil, which require the wearing of a livery or uniform."

"We have, as the great and dominant norm of dress, the broad principle of conspicuous waste. Subsidiary to this principle, and as a corollary under it, we get as a second norm the principle of conspicuous leisure...Beyond these two principles there is a third of scarcely less constraining force...Dress must not only be conspicuously expensive and inconvenient, it must at the same time be up to date...This principle of novelty is another corollary under the law of conspicuous waste...If none of last season's apparel is carried over and made further use of during the present season, the wasteful expenditure on dress is greatly increased...any change in the fashions must conform to the requirement of wastefulness."

"We might naturally expect that the fashions should show a well-marked trend in the direction of some one or more types of apparel eminently becoming to the human form; and we might even feel that we have substantial ground for the hope that today, after all the ingenuity and effort which have been spent on dress these many years, the fashions should have achieved a relative perfection and a relative stability, closely approximating to a permanently tenable artistic ideal. But such is not the case...the assertion freely goes uncontradicted that styles in vogue two thousand years ago are more becoming than the most elaborate and painstaking constructions of today."

"Wealth has by no means yet lost its utility as a honorific evidence of the owner's prepotence."

"What is not doubtful, in the steel business or in any of the other industrial enterprises that run on a similar scale and a similar level of technology, is that the owners of the corporate capital have come in for a very substantial body of intangible assets of this kind, and that these assets of capitalized free income will foot up to several times the total value of the material assets which underlie them."

"Whatever approves itself to us on any ground at the outset, presently comes to appeal to us as a gratifying thing in itself; it comes to rest in our habits of thought as substantially right."

"When an attempted reform involves the suppression or thorough-going remodeling of an institution of first-rate importance in the conventional scheme, it is immediately felt that a serious derangement of the entire scheme would result... that a readjustment of the structure to the new form taken on by one of its chief elements would be a painful and tedious, if not a doubtful process."

"When individuals, or even considerable groups of men, are segregated from a higher industrial culture and exposed to a lower cultural environment, or to an economic situation of a more primitive character, they quickly show evidence of reversion toward the spiritual features which characterize the predatory type; and it seems probable that the dolicho-blond type of European man is possessed of a greater facility for such reversion to barbarism than the other ethnic elements with which that type is associated in the Western culture."

"When the community passes from peaceable savagery to a predatory phase of life... opportunity and the incentive to emulate increase greatly... The activity of the men more and more takes on the character of exploit; and an invidious comparison... grows continually easier and more habitual. Tangible evidences of prowess?trophies?find a place in men's habits of thought as an essential feature... and booty serves as prima facie evidence of successful aggression...as a conventional evidence of successful contest. Therefore... the obtaining of goods by other methods than seizure comes to be accounted unworthy...Labor acquires a character of irksomeness by virtue of the indignity imputed to it."

"When the predatory habit of life has been settled upon the group by long habituation, it becomes the able-bodied man's accredited office in the social economy to kill, to destroy such competitors in the struggle for existence as attempt to resist or elude him, to overcome and reduce to subservience those alien forces that assert themselves refractorily in the environment."

"When the quasi-peaceable stage of industry is reached, with its fundamental institution of chattel slavery, the general principle, more or less rigorously applied, is that the base, industrious class should consume only what may be necessary to their subsistence. In the nature of things, luxuries and the comforts of life belong to the leisure class. Under the tabu, certain victuals, and more particularly certain beverages, are strictly reserved for the use of the superior class."

"Wherever the canon of conspicuous leisure has a chance undisturbed to work out its tendency, there will therefore emerge a secondary, and in a sense spurious, leisure class?abjectly poor and living in a precarious life of want and discomfort, but morally unable to stoop to gainful pursuits."

"Wherever the circumstances or traditions of life lead to an habitual comparison of one person with another in point of efficiency, the instinct of workmanship works out in an emulative or invidious comparison of persons...In any community where such an invidious comparison of persons is habitually made, visible success becomes an end sought for its own utility as a basis of esteem. Esteem is gained and dispraise is avoided by putting one's efficiency in evidence. The result is that the instinct of workmanship works out in an emulative demonstration of force."

"While the proximate ground of discrimination may be of another kind, still the pervading principle and abiding test of good breeding is the requirement of a substantial and patent waste of time. There may be some considerable range of variation in detail within the scope of this principle, but they are variations of form and expression, not of substance."

"With many qualifications?with more qualifications as the patriarchal tradition has gradually weakened?the general rule is felt to be right and binding that women should consume only for the benefit of their masters."

"With the exception of the instinct of self-preservation, the propensity for emulation is probably the strongest and most alert and persistent of the economic motives proper...as regards the Western civilized communities ...it expresses itself in some form of conspicuous waste."

"With the growth of settled industry... the possession of wealth gains in relative importance and effectiveness as a customary basis of repute and esteem...not that successful predatory aggression or warlike exploit ceases to call out the approval and admiration of the crowd ...but the opportunities for gaining distinction by means of this direct manifestation of superior force grow less available."

"With the primitive barbarian... "honorable" seems to connote nothing else than assertion of superior force...The naive, archaic habit of construing all manifestations of force in terms of personality or "will power" greatly fortifies this conventional exaltation of the strong hand...This holds true to an extent also in the more civilized communities of the present day."

"Within the nation the enlightened principles of self-help and free contract have given rise to vested interests which control the industrial system for their own use and thereby come in for a legal right to the community's net output of product over cost. Each of these vested interests habitually aims to take over as much as it can of the lucrative traffic that goes on and to get as much as it can out of the traffic, at the cost of the rest of the community."

"Without reflection or analysis, we feel that what is inexpensive is unworthy. "A cheap coat makes a cheap man.""

"Women have been required not only to afford evidence of a life of leisure, but even to disable themselves for useful activity...the high heel, the skirt, the impracticable bonnet, the corset... are so many items of evidence to the effect that... the woman is still, in theory, the economic dependent of the man?that, perhaps in a highly idealized sense, she still is the man's chattel. The homely reason for all this conspicuous leisure and attire on the part of women lies in the fact that they are servants to whom, in the differentiation of economic functions, has been delegated the office of putting in evidence their master's ability to pay."