Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

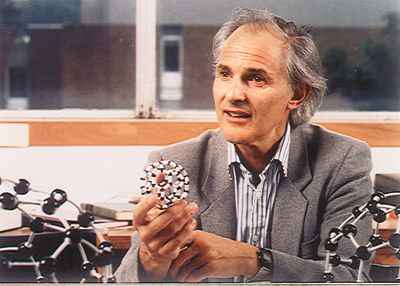

Peter Medawar, fully Sir Peter Brian Medawar

Brazilian-born British Biologist who worked on graft rejection, awarded Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

"It is the great glory as well as the great threat of science that everything which is in principle possible can be done if the intention to do it is sufficiently resolute."

"It would have been a great disappointment to me if Vibration did not somewhere make itself felt, for all scientistic mystics either vibrate in person or find themselves resonant with cosmic vibrations; but I am happy to say that on page 266 Teilhard will be found to do so."

"Life is born and propagates itself on the earth as a solitary pulsation."

"It is written in an all but totally unintelligible style, and this is construed as prima-facie evidence of profundity. (At present this applies only to works of French authorship; in later Victorian and Edwardian times the same deference was thought due to Germans, with equally little reason.) It is because Teilhard has such wonderful deep thoughts that he's so difficult to follow --- really it's beyond my poor brain but doesn't that just show how profound and important it must be?"

"Nor is much use listening to accounts of what scientists say they do, for their opinions var widely enough to accommodate almost any methodological hypothesis we may care to devise. Only unstudied evidence will do ? and that means listening at a keyhole."

"It just so happens that during the 1950s, the first great age of molecular biology, the English schools of Oxford and particularly Cambridge produced more than a score of graduates of quite outstanding ability ? much more brilliant, inventive, articulate and dialectically skilful than most young scientists; right up in the Watson class. But Watson had one towering advantage over all of them: in addition to being extremely clever he had something important to be clever about. This is an advantage which scientists enjoy over most other people engaged in intellectual pursuits, and they enjoy it at all levels of capability. To be a first-rate scientist it is not necessary (and certainly not sufficient) to be extremely clever, anyhow in a pyrotechnic sense. One of the great social revolutions brought about by scientific research has been the democratization of learning. Anyone who combines strong common sense with an ordinary degree of imaginativeness can become a creative scientist, and a happy one besides, in so far as happiness depends upon being able to develop to the limit of one?s abilities."

"Observation is the generative act in scientific discovery. For all its aberrations, the evidence of the senses is essentially to be relied upon ? provided we observe nature as a child does, without prejudices and preconceptions, but with that clear and candid vision which adults lose and scientists must strive to regain."

"No scientist is admired for failing in the attempt to solve problems that lie beyond his competence. The most he can hope for is the kindly contempt earned by the Utopian politician. If politics is the art of the possible, research is surely the art of the soluble. Both are immensely practical-minded affairs."

"Psychoanalytic theory is the most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century and a terminal product as well?something akin to a dinosaur or zeppelin in the history of ideas, a vast structure of radically unsound design and with no posterity."

"Scientific theories (I have said) begin as imaginative constructions. The begin, if you like, as stories, and the purpose of the critical or rectifying episode in scientific reasoning is precisely to find out whether or not these stories are stories about real life. Literal or empiric truthfulness is not therefore the strating-point of scientific enquiry, but rather the direction in which scientific reasoning moves. If this is a fair statement, it follows that scientific and poetic or imaginative accounts of the world are not distinguishable in their origins. They start in parallel, but diverge from one another at some later stge. We all tell stories, but the stories differ in the purposes we expect them to fulfil and in the kinds of evaluations to which they are exposed."

"Scientists are entitled to be proud of their accomplishments, and what accomplishments can they call ?theirs? except the things they have done or thought of first? People who criticize scientists for wanting to enjoy the satisfaction of intellectual ownership are confusing possessiveness with pride of possession. Meanness, secretiveness and, sharp practice are as much despised by scientists as by other decent people in the world of ordinary everyday affairs; nor, in my experience, is generosity less common among them, or less highly esteemed."

"Scientific discovery is a private event, and the delight that accompanies it, or the despair of finding it illusory, does not travel. One scientist may get great satisfaction from another?s work and admire it deeply; it may give him great intellectual pleasure; but it gives him no sense of participation in the discovery, it does not carry him away, and his appreciation of it does not depend on his being carried away. If it were otherwise the inspirational origin of scientific discovery would never have been in doubt."

"Simultaneous discovery is utterly commonplace, and it was only the rarity of scientists, not the inherent improbability of the phenomenon, that made it remarkable in the past. Scientists on the same road may be expected to arrive at the same destination, often not far apart."

"That there is indeed a limit upon science is made very likely by the existence of questions that science cannot answer, and that no conceivable advance of science would empower it to answer. I have in mind such questions as: How did everything begin? What are we all here for? What is the point of living?"

"The alternative to thinking in evolutionary terms is not to think at all."

"The art of research ? the art of making difficult problems soluble by devising means of getting at them."

"The ballast of factual information, so far from being just about to sink us, is growing daily less. The factual burden of a science varies inversely with its degree of maturity. As a science advances, particular facts are comprehended within, and therefore in a sense annihilated by, general statements of steadily increasing explanatory power and compass ? whereupon the facts need no longer be known explicitly, that is, spelled out and kept in mind. In all sciences we are being progressively relieved of the burden of singular instances, the tyranny of the particular. We need no longer record the fall of every apple."

"The attempt to discover and promulgate the truth is nevertheless an obligation upon all scientists, one that must be persevered in no matter what the rebuffs?for otherwise what is the point in being a scientist?"

"The bells which toll for mankind are ? most of them, anyway ? like the bells of Alpine cattle; they are attached to our own necks, and it must be our fault if they do not make a cheerful and harmonious sound."

"The formulation of a natural ?law? always begins as an imaginative exploit, and without imagination scientific thought is barren."

"The critical task of science is not complete and never will be, for it is the merest truism that we do not abandon mythologies and superstitions, but merely substitute new variants for old."

"The human mind treats a new idea the same way the body treats a strange protein; it rejects it."

"The idea of na‹ve or innocent observation is philosophers? make-believe."

"The lives of scientists, considered as Lives, almost always make dull reading. For one thing, the careers of the famous and the merely ordinary fall into much the same pattern, give or take an honorary degree or two, or (in European countries) an honorific order. It could be hardly otherwise. Academics can only seldom lead lives that are spacious or exciting in a worldly sense. They need laboratories or libraries and the company of other academics. Their work is in no way made deeper or more cogent by privation, distress or worldly buffetings. Their private lives may be unhappy, strangely mixed up or comic, but not in ways that tell us anything special about the nature or direction of their work. Academics lie outside the devastation area of the literary convention according to which the lives of artists and men of letters are intrinsically interesting, a source of cultural insight in themselves. If a scientist were to cut his ear off, no one would take it as evidence of a heightened sensibility; if a historian were to fail (as Ruskin did) to consummate his marriage, we should not suppose that our understanding of historical scholarship had somehow been enriched."

"The length of university schooling is far more important to those whose education ends with graduation than to those for whom education is an indefinitely continued process."

"The Phenomenon of Man stands square in the tradition of Naturphilosophie, a philosophical indoor pastime of German origin which does not seem even by accident (though there is a great deal of it) to have contributed anything of permanent value to the storehouse of human thought."

"The Phenomenon of Man is anti-scientific in temper (scientists are shown up as shallow folk skating about on the surface of things), and, as if that were not recommendation enough, it was written by a scientist, a fact which seems to give it particular authority and weight. Laymen firmly believe that scientists are one species of person. They are not to know that different branches of science require very different aptitudes and degrees of skill for their prosecution. Teilhard practiced an intellectually unexacting kind of science in which he achieved a moderate proficiency. He has no grasp of what makes a logical argument or of what makes for proof. He does not even preserve the common decencies of scientific writing, though his book is professedly a scientific treatise."

"The Phenomenon of Man was introduced to the English-speaking world by Sir Julian Huxley, who, like myself, finds Teilhard somewhat difficult to follow ('If I understood him aright'; 'here his thought is not fully clear to me'; etc.). Unlike myself, Sir Julian finds Teilhard in possession of a 'rigorous sense of values', one who 'always endeavored to think concretely'; he was speculative, to be sure, but his speculation was 'always disciplined by logic'. But then it does not seem to me that Huxley expounds Teilhard's argument; his Introduction does little more than to call attention to parallels between Teilhard's thinking and his own. Chief among these is the cosmic significance attached to a suitably generalized conception of evolution --- a conception so diluted or attenuated in the course of being generalized as to cover all events or phenomena that are not immobile in time. In particular, Huxley applauds the, in my opinion, mistaken belief that the so-called 'psychosocial evolution' of mankind and the genetical evolution of living organisms generally are two episodes of a continuous integral process (though separated by a 'critical point', whatever that may mean). Yet for all this Huxley finds it impossible to follow Teilhard 'all the way in his gallant attempt to reconcile the supernatural elements in Christianity with the facts and implications of evolution'. But, bless my soul, this reconciliation is just what Teilhard's book is about!"

"The similarity between them is not the taxonomic key to some other, deeper, affinity, and our recognizing its existence marks the end, not the inauguration, of a train of thought."

"The purpose of scientific enquiry is not to compile an inventory of factual information, nor to build up a totalitarian world picture of natural Laws in which every event that is not compulsory is forbidden. We should think of it rather as a logically articulated structure of justifiable beliefs about nature."

"The USA is so enormous, and so numerous are its schools, colleges and religious seminaries, many devoted to special religious beliefs ranging from the unorthodox to the dotty, that we can hardly wonder at its yielding a more bounteous harvest of gob."

"The scientist values research by the size of its contribution to that huge, logically articulated structure of ideas which is already, though not yet half built, the most glorious accomplishment of mankind. The humanist must value his research by different but equally honorable standards, particularly by the contribution it makes, directly or indirectly, to our understanding of human nature and conduct, and human sensibility."

"There is much else in the literary idiom of nature-philosophy: nothing-buttery, for example, always part of the minor symptomatology of the bogus."

"There are no summits without abysses."

"There is no paradox here: it just so happens that what are usually thought of as two alternative accounts of one process of thought are in fact two successive and complementary episodes of thought that occur in every advance of scientific understanding."

"There is no place for apodictic certainty in science."

"There is no such thing as a Scientific Mind. Scientists are people of very dissimilar temperaments doing different things in very different ways. Among scientists are collectors, classifiers and compulsive tidiers-up; many are detectives by temperament and many are explorers; some are artists and others artisans. There are poet-scientists and philosopher-scientists and even a few mystics. What sort of mind or temperament can all these people be supposed to have in common? Obligative scientists must be very rare, and most people who are in fact scientists could easily have been something else instead."

"To be creative, scientists need libraries and laboratories and the company of other scientists; certainly a quiet and untroubled life is a help. A scientist?s work is in no way deepened or made more cogent by privation, anxiety, distress, or emotional harassment. To be sure, the private lives of scientists may be strangely and even comically mixed up, but not in ways that have any special bearing n the nature and quality of their work. If a scientist were to cut off an ear, no one would interpret such an action as evidence of an unhappy torment of creativity; nor will a scientist be excused any bizarrerie, however extravagant, on the grounds that he is a scientist, however brilliant."

"Very simple-minded people think that if Newton had died prematurely we should still be at our wits? end to account for the fall of apples."

"Watson's childlike vision makes them seem like the creatures of a Wonderland, all at a strange contentious noisy tea-party which made room for him because for people like him, at this particular kind of party, there is always room."

"What scientists do has never been the subject of a scientific, that is, an ethological enquiry. It is of no use looking to scientific ?papers?, for they not merely conceal but actively misrepresent the reasoning that goes into the work they describe."

"We shall not read it for its sociological insights, which are non-existent, nor as science fiction, because it has a general air of implausibility; but there is one high poetic fancy in the New Atlantis that stays in the mind after all its fancies and inventions have been forgotten. In the New Atlantis, an island kingdom lying in very distant seas, the only commodity of external trade is ? light: Bacon's own special light, the light of understanding."

"We cannot point to a single definitive solution of any one of the problems that confront us ? political, economic, social or moral, that is, having to do with the conduct of life. We are still beginners, and for that reason may hope to improve. To deride the hope of progress is the ultimate fatuity, the last word in poverty of spirit and meanness of mind. There is no need to be dismayed by the fact that we cannot yet envisage a definitive solution of our problems, a resting-place beyond which we need not try to go."

"What shows a theory to be inadequate or mistaken is not, as a rule, the discovery of a mistake in the information that led us to propound it; more often it is the contradictory evidence of a new observation which we were led to make because we held that theory."

"We wring our hands over the miscarriages of technology and take its benefactions for granted. We are dismayed by air pollution but not proportionately cheered up by, say, the virtual abolition of poliomyelitis."

"When asked to make the formal declaration that I did not intend to overthrow the Constitution of the United States, I was fool enough to reply that I had no such purpose, but that were I to do it by mistake I should be inexpressibly contrite."

"When the end of the world is mentioned, the idea that leaps into our minds is always one of catastrophe."

"Yet the greater part of it, I shall show, is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself."