Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

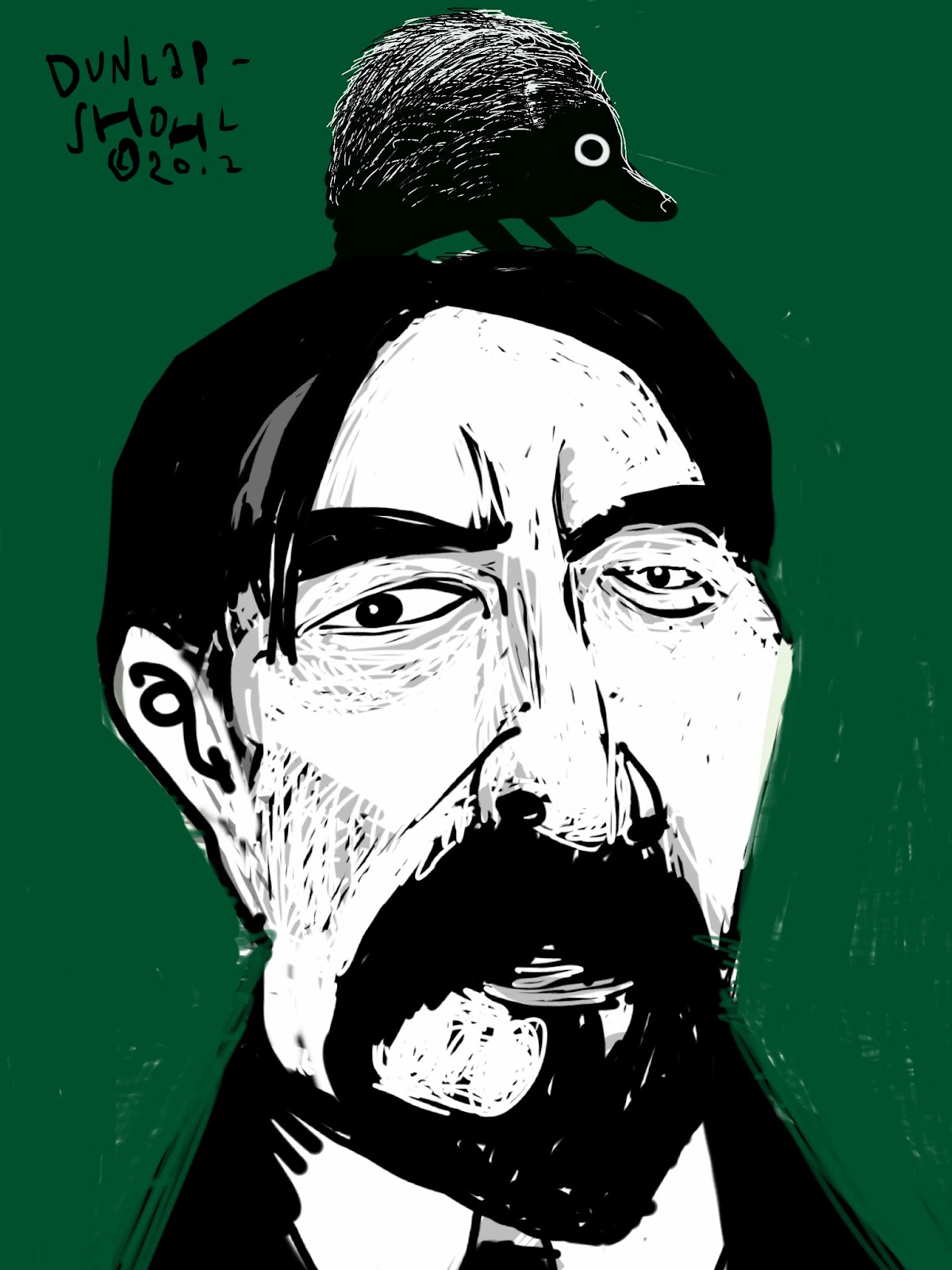

Thorstein Veblen, fully Thorstein Bunde Veblen, born Torsten Bunde Veblen

Norwegian-American Sociologist and Economist, Leader of the Institutional Economics Movement

"In general, the longer the habituation, the more unbroken the habit, and the more nearly it coincides with previous habitual forms of the life process, the more persistently will the given habit assert itself. The habit will be stronger if the particular traits of human nature which its action involves, or the particular aptitudes that find exercise in it, are traits or aptitudes that are already largely and profoundly concerned in the life process or that are intimately bound up with the life history."

"In itself and in its consequences the life of leisure is beautiful and ennobling in all civilised men's eyes."

"In later times, and particularly in modern times and in the civilized countries, those immemorial principles of privilege equitably vested in the master class have fallen into discredit as being not sufficiently grounded in fact; so that mastery and servitude are disallowed and have disappeared from the range of legitimate institutions. The enlightened principles of self-help and personal equality do not tolerate these things. However, they do tolerate free income from investments. Indeed, the most consistent and most reputable votaries of the modern point of view commonly subsist on such income."

"In making use of the term "invidious"... there is no intention to extol or depreciate, or to commend or deplore any of the phenomena which the word is used to characterize. The term is used in a technical sense as describing a comparison of persons with a view to rating and grading them in respect of relative worth or value?in an aesthetic or moral sense?and so awarding and defining the relative degrees of complacency with which they may legitimately be contemplated by themselves and by others. An invidious comparison is a process of valuation of persons in respect of worth."

"In modern civilized communities... the members of each stratum accept as their ideal of decency the scheme of life in vogue in the next higher stratum."

"In modern civilized communities... the norm of reputability imposed by the upper class extends its coercive influence with but slight hindrance down through the social structure to the lowest strata... the members of each stratum accept as their ideal of decency the scheme of life in vogue in the next higher stratum."

"In modern communities, where the dominant economic and legal feature of the community's life is the institution of private property, one of the salient features of the code of morals is the sacredness of property."

"In persons of a delicate sensibility who have long been habituated to gentle manners, the sense of the shamefulness of manual labor may become so strong that, at a critical juncture, it will even set aside the instinct of self-preservation."

"In point of natural endowment the pecuniary man compares with the delinquent in much the same way as the industrial man compares with the good-natured shiftless dependent. The ideal pecuniary man is like the ideal delinquent in his unscrupulous conversion of goods and persons to his own ends, and in a callous disregard of the feelings and wishes of others and of the remoter effects of his actions; but he is unlike him in possessing a keener sense of status, and in working more consistently and farsightedly to a remoter end."

"In point of substantial merit the law school belongs in the modern university no more than a school of fencing or dancing."

"in so far as this management creates an assured strategic advantage for any given business concern, the result is a vested interest. This may then eventually be capitalized in due form, as a body of intangible assets. As such it goes to augment the business community's accumulated wealth. And the country is statistically richer per capita. A vested interest is a marketable right to get something for nothing. This does not mean that the vested interests cost nothing. They may even come high. Particularly may their cost seem high if the cost to the community is taken into account, as well as the expenditure incurred by their owners for their production and up-keep. Vested interests are immaterial wealth, intangible assets. As regards their nature and origin, they are the outgrowth of three main lines of businesslike management: (a) Limitation of supply, with a view to profitable sales; (b) Obstruction of traffic, with a view to profitable sales; and (c) Meretricious publicity, with a view to profitable sales."

"In the early barbarian, or predatory stage proper, the test of fitness was prowess, in the naive sense of the word. To gain entrance to the class, the candidate had to be gifted with clannishness, massiveness, ferocity, unscrupulousness, and tenacity of purpose. These were the qualities that counted toward the accumulation and continued tenure of wealth."

"In the last analysis the value of manners lies in the fact that they are the voucher of a life of leisure...the acquisition of some proficiency in decorum is incumbent on all who aspire to a modicum of pecuniary decency."

"In the later barbarian culture society attained settled methods of acquisition and possession under the quasi-peaceable regime of status. Simple aggression and unrestrained violence in great measure gave place to shrewd practice and chicanery, as the best approved method of accumulating wealth."

"In the modern community there is also a more frequent attendance at large gatherings of people to whom one's everyday life is unknown... the signature of one's pecuniary strength should be written in characters which he who runs may read. It is evident, therefore, that the present trend of the development is in the direction of heightening the utility of conspicuous consumption as compared with leisure."

"In the modern industrial communities the mechanical contrivances available for the comfort and convenience of everyday life are highly developed...Under the requirement of conspicuous consumption of goods, the apparatus of living has grown so elaborate and cumbrous, in the way of dwellings, furniture, bric-a-brac, wardrobe and meals, that the consumers of these things cannot make way with them in the required manner without help."

"In the modern industrial communities... the apparatus of living has grown so elaborate and cumbrous... that the consumers of these things cannot make way with them in the required manner without help."

"In the priestly life of all anthropomorphic cults the marks of a vicarious consumption of time are visible."

"In the rare cases where it occurs, a failure to increase one's visible consumption when the means for an increase are at hand is felt in popular apprehension to call for explanation, and unworthy motives of miserliness are imputed to those who fall short in this respect."

"In the struggle to outdo one another the city population push their normal standard of conspicuous consumption to a higher point, with the result that a relatively greater expenditure in this direction is required to indicate a given degree of pecuniary decency in the city...this requirement of decent appearance must be lived up to on pain of losing caste."

"In their corporate capacity, these advanced industrial communities are ceasing to be competitors for the means of life or for the right to live?except in so far as the predatory propensities of their ruling classes keep up the tradition of war and rapine...No one of them any longer has any material interest in getting the better of any other. The same is not true in the same degree as regards individuals and their relations to one another."

"In their selection of serviceable goods in the retail market purchasers are guided more by the finish and workmanship of the goods than by any marks of substantial serviceability...the conventional requirement of obvious costliness, as a voucher and a constituent of the serviceability of the goods, leads him to reject as under grade such goods as do not contain a large element of conspicuous waste."

"In this connection, and under the existing conditions of investment and credit, "reasonable returns" means the same thing as "the largest practicable net returns." It all foots up to an application of the familiar principle of "charging what the traffic will bear"; for in the matter of profitable business there is no reasonable limit short of the maximum. In business, the best price is always good enough; but, so also, nothing short of the best price is good enough. Buy cheap and sell dear."

"Institutions are not only themselves the result of a selective and adaptive process which shapes the prevailing or dominant types of spiritual attitude and aptitudes; they are at the same time special methods of life and of human relations, and are therefore in their turn efficient factors of selection."

"Institutions are products of the past process, are adapted to past circumstances, and are therefore never in full accord with the requirements of the present."

"Intangible assets are the capitalized value of income not otherwise accounted for. Such income arises out of business relations rather than out of industry; it is derived from advantages of salesmanship, rather than from productive work; it represents no contribution to the output of goods and services, but only an effectual claim to a share in the "annual dividend," -- on grounds which appear to be legally honest, but which cannot be stated in terms of mechanical cause and effect, or of productive efficiency, or indeed in any terms that involve notions of physical dimensions or of mechanical action. But while intangible assets represent income which accrues out of certain immaterial relations between their owners and the industrial system, and while this income is accordingly not a return for mechanically productive work done, it still remains true, of course, that such income is drawn from the annual product of industry, and that its productive source is therefore the same as that of the returns on tangible assets. The material source of both is the same; and it is only that the basis on which the income is claimed is not the same for both. It is not a difference in respect of the ways and means by which they are created, but only in respect of the ways and means by which these two classes of income are intercepted and secured by the beneficiaries to whom they accrue. The returns on tangible assets are assumed to be a return for the productive use of the plant; returns on intangible assets are a return for the exercise of certain immaterial relations involved in the ownership and control of industry and trade."

"Intangibles of this kind, which represent a "conscientious withdrawal of efficiency," an effectual control of the rate or volume of output, are altogether the most common of immaterial assets, and they make up altogether the largest class of intangibles and the most considerable body of immaterial wealth owned. Land values are of much the same nature as these corporate assets which represent capitalized restriction of output, in that the land values, too, rest mostly on the owner's ability to withhold his property from productive use, and so to drive a profitable bargain. Rent is also a case of charging what the traffic will bear; and rental values should properly be classed with these intangible assets of the larger corporations, which are due to their effectual control of the rate and volume of production. And apart from the rental values of land, which are also in the nature of monopoly values, it is doubtful if the total material wealth in any of the civilized countries will nearly equal the total amount of this immaterial wealth that is owned by the country's business men and the investors for whom they do business. Which evidently comes to much the same as saying that something more than one-half of the net product of the country's industry goes to those persons in whom the existing state of law and custom vests a plenary power to hinder production."

"Invested wealth in large holdings controls the country's industrial system, directly by ownership of the plant, as in the mechanical industries, or indirectly through the market, as in farming. So that the population of these civilized countries now falls into two main classes: those who own wealth invested in large holdings and who thereby control the conditions of life for the rest; and those who do not own wealth in sufficiently large holdings, and whose conditions of life are therefore controlled by these others. It is a division, not between those who have something and those who have nothing -- as many socialists would be inclined to describe it -- but between those who own wealth enough to make it count, and those who do not."

"It appears that the canons of pecuniary reputability do... affect our notions of the attributes of divinity, as well as... of divine communion. It is felt that the divinity must be of a peculiarly serene and leisurely habit of life. And whenever his local habitation is pictured in poetic imagery... the devout word-painter, as a matter of course, brings out before his auditors' imagination a throne with a profusion of the insignia of opulence and power, and surrounded by a great number of servitors...the office of this corps of servants is a vicarious leisure, their time and efforts being in great measure taken up with an industrially unproductive rehearsal of the meritorious characteristics and exploits of the divinity; while the background of the presentation is filled with the shimmer of the precious metals and of the more expensive varieties of precious stones."

"It frequently happens that an element of the standard of living which set out with being primarily wasteful, ends with becoming, in the apprehension of the consumer, a necessary of life; and it may in this way become as indispensable as any other item of the consumer's habitual expenditure."

"it has been a period of unexampled change, -- swift, varied, profound and extensive beyond example. And it follows of necessity that the principles of conduct which were approved and stabilized in the eighteenth century, under the driving exigencies of that age, have not altogether escaped the complications of changing circumstances. They have at least come in for some shrewd interpretation in the course of the nineteenth century. There have been refinements of definition, extensions of application, scrutiny and exposition of implications, as new exigencies have arisen and the established canons have been required to cover unforeseen contingencies; but it has all been done with the explicit reservation that no material innovation shall be allowed to touch the legacy of modern principles handed down from the eighteenth century, and that the vital system of Natural Rights installed in the eighteenth century must not be deranged at any point or at any cost."

"It has been customary in economic theory, and especially among those economists who adhere with least faltering to the body of modernized classical doctrines, to construe this struggle for wealth as being substantially a struggle for subsistence... But in all progressing communities... industrial efficiency is presently carried to such a pitch as to afford something appreciably more than a bare livelihood... The motive that lies at the root of ownership is emulation; and the same motive of emulation continues active in the further development of the institution... and in the development of all those features of the social structure which this institution of ownership touches."

"It is a matter of course and of absolute necessity to the conduct of business, that any discretionary businessman must be free to deal or not to deal in any given case; to limit or withhold the equipment under his control, without reservation. Business discretion and business strategy, in fact, has no other means by to work out its aims. So that, in effect, all business sagacity reduces itself in the last analysis to judicious use of sabotage."

"It is always sound business to take any obtainable net gain, at any cost and at any risk to the rest of the community."

"It is currently believed that manners have progressively deteriorated as society has receded from the patriarchal stage."

"It is especially the latter-day system of transport and communication as it works out under the new order highly mechanical and exactingly scheduled for time, date and place -- that so controls and standardizes the ordinary life of the common man on mechanical lines."

"It is felt by all men that a right and enlightened sense of the true, the beautiful, and the good demands that in all expenditure on the sanctuary anything that might serve the comfort of the worshipper should be conspicuously absent. If any element of comfort is admitted in the fittings of the sanctuary, it should be at least scrupulously screened and masked under an ostensible austerity."

"It is much more difficult to recede from a scale of expenditure once adopted than it is to extend the accustomed scale in response to an accession of wealth."

"It is necessary to come up to a certain, somewhat indefinite, conventional standard of wealth; just as in the earlier predatory stage it is necessary for the barbarian man to come up to the tribe's standard of physical endurance, cunning, and skill at arms. A certain standard of wealth in the one case, and of prowess in the other, is a necessary condition of reputability, and anything in excess of this normal amount is meritorious."

"It is needless to point out the close analogy at this point between the priestly office and the office of the footman. It is pleasing to our sense of what is fitting... to recognize in the obvious perfunctoriness of the service that it is a pro forma execution only. There should be no show of agility or of dexterous manipulation in the execution of the priestly office, such as might suggest a capacity for turning off the work."

"It is not that these and their like are ready with "a satisfactory constructive program," such as the people of the uplift require to be shown before they will believe that things are due to change. It is something of the simpler and cruder sort, such as history is full of, to the effect that whenever and so far as the time-worn rules no longer fit the new material circumstances they presently fail to carry conviction as they once did. Such wear and tear of institutions is unavoidable where circumstances change; and it is through the altered personal equation of those elements of the population which are most directly exposed to the changing circumstances that the wear and tear of institutions may be expected to take effect. To these untidy creatures of the New Order common honesty appears to mean vaguely something else, perhaps something more exacting, than what was "nominated in the bond" at the time when the free bargain and self-help were written into the moral constitution of Christendom by the handicraft industry and the petty trade. And why should it not"

"It is not unusual to hear those persons who dispense salutary advice and admonition to the community express themselves forcibly upon the far-reaching pernicious effects which the community would suffer from such relatively slight changes as the disestablishment of the Anglican Church, an increased facility of divorce, adoption of female suffrage, prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages, abolition or restriction of inheritances, etc. Any one of these innovations would, we are told, "shake the social structure to its base," "reduce society to chaos," "subvert the foundations of morality," "make life intolerable," "confound the order of nature," etc."

"It is of course only as to the economic value of this school of aesthetic teaching that anything is intended to be said or can be said here. What is said is not to be taken in the sense of depreciation, but chiefly as a characterization of the tendency of this teaching in its effect on consumption and on the production of consumable goods."

"It is only within narrow limits, and then only in a Pickwickian sense, that honesty is the best policy."

"It is scarcely necessary to describe this modern system of principles that still continues to govern human intercourse among the civilized peoples, or to attempt an exposition of its constituent articles. It is all to be had in exemplary form, ably incorporated in such familiar documents as the American Declaration of Independence, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, and the American Constitution; and it is all to be found set forth with all the circumstance of philosophical and juristic scholarship in the best work of such writers as John Locke. Montesquieu. Adam Smith, or Blackstone."

"It is true of dress in even a higher degree than of most other items of consumption, that people will undergo a very considerable degree of privation in the comforts or the necessaries of life in order to afford what is considered a decent amount of wasteful consumption; so that it is by no means an uncommon occurrence, in an inclement climate, for people to go ill clad in order to appear well dressed."

"It is, in effect, for this continued growth of their market, caused by the growth of population, that the business men claim credit when they "point with pride" to the resourcefulness and quick initiative with which they have "developed the country,"."

"it may well be that the frame of mind engendered by this training in matter-of-fact ways of thinking will presently so shape popular sentiment that all income from property, simply on the basis of ownership, will be disallowed, whether the property is tangible or intangible. All that is a speculative question running into the future."

"It should be added, as is plain to all men, that these ordinary and normal processes of private initiative never do provide employment for all the men available. In fact, unemployment is an ordinary and normal phenomenon. So that even in the present emergency, when the peoples of Christendom are suffering privation together for want of goods needed for immediate use, the ordinary and normal processes of private initiative are not to be depended on to employ all the available man power for productive industry. The reason is well known to all men; so well known as to be uniformly taken for granted as a circumstance which is beyond human remedy. It is the simple and obvious fact that the ordinary and normal processes of private initiative are the same thing as "business as usual," which controls industry with a view to private gain in terms of price; and the largest private, gain in terms of price cannot be had by employing all the available man power and speeding up the industries to their highest productivity, even when all the peoples of Christendom are suffering privation together for want of the ordinary necessaries of life. Private initiative means business enterprise, not industry."

"It would be extremely difficult to find a modern civilized residence or public building which can claim anything better than relative inoffensiveness in the eyes of anyone who will dissociate the elements of beauty from those of honorific waste...the dead walls of the sides and back of these structures, left untouched by the hands of the artist, are commonly the best feature of the building."