Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

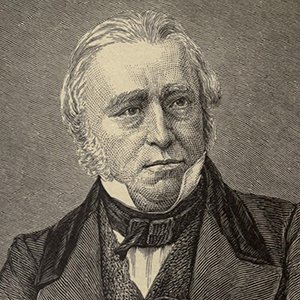

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"The correctness which the last century prized so much resembles the correctness of those pictures of the garden of Eden which we see in old Bibles. We have an exact square, enclosed by the rivers Pison, Gibon, Hiddekel, and Euphrates, each with a convenient bridge in the centre, rectangular beds of flowers, a long canal, neatly bricked and railed in, the tree of knowledge, clipped like one of the limes behind the Tuilleries, standing in the centre of the grand alley, the snake twined round it, the man on the right hand, the woman on the left, and the beasts drawn up in an exact circle round them. In one sense the picture is correct enough. That is to say, the squares are correct; the circles are correct; the man and the woman are in a most correct line with the tree; and the snake forms a most correct spiral."

"The dearest interests of parties have frequently been staked on the results of the researches of antiquaries."

"The division of labour operates on the productions of the orator as it does on those of the mechanic. It was remarked by the ancients that the Pentathlete, who divided his attention between several exercises, though he could not vie with a boxer in the use of the cestus, or with one who had confined his attention to running in the contest of the Stadium, yet enjoyed far greater vigour and health than either. It is the same with the mind. The superiority of technical skill is often more than compensated by the inferiority in general intelligence. And this is peculiarly the case in politics. States have always been best governed by men who have taken a wide view of public affairs, and who have rather a general acquaintance with many sciences than a perfect mastery of one. The union of the political and military departments in Greece contributed not a little to the splendour of its early history. After their separation, more skilful generals and greater speakers appeared; but the breed of statesmen dwindled and became almost extinct. Themistocles or Pericles would have been no match for Demosthenes in the assembly or for Iphicrates in the field. But surely they were incomparably better fitted than either for the supreme direction of affairs."

"The dervise in the Arabian tale did not hesitate to abandon to his comrade the camels with their load of jewels and gold, while he retained the casket of that mysterious juice which enabled him to behold at one glance all the hidden riches of the universe. Surely it is no exaggeration to say that no external advantage is to be compared with that purification of the intellectual eye which gives us to contemplate the infinite wealth of the mental world, all the hoarded treasures of its primeval dynasties, all the shapeless ore of its yet unexplored mines. This is the gift of Athens to man. Her freedom and her power have for more than twenty centuries been annihilated; her people have degenerated into timid slaves; her language into a barbarous jargon; her temples have been given up to the successive depredations of Romans, Turks, and Scotchmen; but her intellectual empire is imperishable. And when those who have rivalled her greatness shall have shared her fate; when civilization and knowledge shall have fixed their abode in distant continents; when the sceptre shall have passed away from England; when, perhaps, travellers from distant regions shall in vain labour to decipher on some mouldering pedestal the name of our proudest chief; shall hear savage hymns chaunted to some misshapen idol over the ruined dome of our proudest temple; and shall see a single naked fisherman wash his nets in the river of ten thousand masts;—her influence and her glory will still survive,—fresh in eternal youth, exempt from mutability and decay, immortal as the intellectual principle from which they derived their origin, and over which they exercise their control."

"The doctrine of a moral sense may be very unphilosophical, but we do not think that it can be proved to be pernicious. Men did not entertain certain desires and aversions because they believed in a moral sense, but they gave the name of moral sense to a feeling which they found in their minds, however it came there. If they had given it no name at all, it would still have influenced their actions; and it will not be very easy to demonstrate that it has influenced their actions the more because they have called it the moral sense. The theory of the original contract is a fiction, and a very absurd fiction; but in practice it meant what the greatest happiness principle if ever it becomes a watchword of political warfare will mean,—that is to say, whatever served the turn of those who used it. Both the one expression and the other sound very well in debating clubs; but in the real conflicts of life our passions and interests bid them stand aside and know their place. The greatest happiness principle has always been latent under the words social contract, justice, benevolence, patriotism, liberty, and so forth, just as far as it was for the happiness, real or imagined, of those who used these words to promote the greatest happiness of mankind. And of this we may be sure, that the words greatest happiness will never in any man’s mouth mean more than the greatest happiness of others which is consistent with what he thinks his own."

"The dust and silence of the upper shelf."

"The doctrine which must surely command universal assent is this: that every association of human beings which exercises any power whatever, that is to say, every association of human beings, is bound, as such association, to profess a religion. Imagine the effect which would follow if this principle were in force during four-and-twenty hours. Take one instance out of a million. A stage-coach company has power over its horses. This power is the property of God. It is used according to the will of God when it is used with mercy. But the principle of mercy can never be truly or permanently entertained in the human breast without continual reference to God. The powers, therefore, that dwell in individuals acting as a stage-coach company can only be secured for right uses by applying to them a religion. Every stage-coach company ought, therefore, in its collective capacity, to profess some one faith, to have its articles, and its public worship, and its tests. That this conclusion, and an infinite number of other conclusions equally strange, follow of necessity from Mr. Gladstone’s principles, is as certain as it is that two and two make four. And if the legitimate conclusions be so absurd, there must be something unsound in the principle."

"The difference between the philosophy of Bacon and that of his predecessors cannot, we think, be better illustrated than by comparing his views on some important subjects with those of Plato. We select Plato, because we conceive that he did more than any other person towards giving to the minds of speculative men that bent which they retained till they received from Bacon a new impulse in a diametrically opposite direction."

"The difference between one man and another is by no means so great as the superstitious crowd supposes. - But the same feelings which in ancient Rome produced the apotheosis of a popular emperor, and in modern times the canonization of a devout prelate, lead men to cherish an illusion which furnishes them with something to adore."

"The effect of oratory will always to a great extent depend on the character of the orator. There perhaps were never two speakers whose eloquence had more of what may be called the race, more of the flavour imparted by moral qualities, than Fox and Pitt. The speeches of Fox owe a great part of their charm to that warmth and softness of heart, that sympathy with human suffering, that admiration for everything great and beautiful, and that hatred of cruelty and injustice, which interest and delight us even in the most defective reports. No person, on the other hand, could hear Pitt without perceiving him to be a man of high, intrepid, and commanding spirit, proudly conscious of his own rectitude and of his own intellectual superiority, incapable of the low vices of fear and envy, but too prone to feel and to show disdain. Pride, indeed, pervaded the whole man, was written in the harsh, rigid lines of his face, was marked by the way in which he walked, in which he sate, in which he stood, and, above all, in which he bowed. Such pride, of course, inflicted many wounds. It may confidently be affirmed that there cannot be found in all the ten thousand invectives written against Fox a word indicating that his demeanour had ever made a single personal enemy. On the other hand, several men of note who had been partial to Pitt, and who to the last continued to approve his public conduct and to support his administration, Cumberland, for example, Boswell, and Mathias, were so much irritated by the contempt with which he treated them that they complained in print of their wrongs. But his pride, though it made him bitterly disliked by individuals, inspired the great body of his followers in Parliament and throughout the country with respect and confidence. They took him at his own valuation."

"The effect of historical reading is analogous, in many respects, to that produced by foreign travel. The student, like the tourist, is transported into a new state of society. He sees new fashions. He hears new modes of expression. His mind is enlarged by contemplating the wide diversities of laws, of morals, and of manners. But men may travel far, and return with minds as contracted as if they had never stirred from their own market-town. In the same manner, men may know the dates of many battles, and the genealogies of many royal houses, and yet be no wiser. Most people look at past times as princes look at foreign countries. More than one illustrious stranger has landed on our island amidst the shouts of a mob, has dined with the king, has hunted with the master of the stag-hounds, has seen the guard reviewed, and a knight of the garter installed, has cantered along Regent Street, has visited St. Paul’s and noted down its dimensions, and has then departed, thinking that he has seen England. He has, in fact, seen a few public buildings, public men, and public ceremonies. But of the vast and complex system of society, of the fine shades of national character, of the practical operation of government and laws, he knows nothing. He who would understand these things rightly must not confine his observations to palaces and solemn days. He must see ordinary men as they appear in their ordinary business and in their ordinary pleasures. He must mingle in the crowds of the exchange and the coffee-house. He must obtain admittance to the convivial table and the domestic hearth. He must bear with vulgar expressions. He must not shrink from exploring even the retreats of misery. He who wishes to understand the condition of mankind in former ages must proceed on the same principle. If he attends only to public transactions, to wars, congresses, and debates, his studies will be as unprofitable as the travels of those imperial, royal, and serene sovereigns who form their judgment of our island from having gone in state to a few fine sights, and from having held formal conferences with a few great officers."

"The effect of the great freedom of the press in England has been, in a great measure, to destroy this distinction, and to leave among us little of what I call Oratory Proper. Our legislators, our candidates, on great occasions even our advocates, address themselves less to the audience than to the reporters. They think less of the few hearers than of the innumerable readers. At Athens the case was different; there the only object of the speaker was immediate conviction and persuasion. He, therefore, who would justly appreciate the merit of the Grecian orators should place himself, as nearly as possible, in the situation of their auditors: he should divest himself of his modern feelings and acquirements, and make the prejudices and interests of the Athenian citizen his own. He who studies their works in this spirit will find that many of those things which to an English reader appear to be blemishes—the frequent violation of those excellent rules of evidence by which our courts of law are regulated,—the introduction of extraneous matter,—the reference to considerations of political expediency in judicial investigations,—the assertions without proof,—the passionate entreaties,—the furious invectives,—are really proofs of the prudence and address of the speakers. He must not dwell maliciously on arguments or phrases, but acquiesce in his first impressions. It requires repeated perusal and reflection to decide rightly on any other portion of literature. But with respect to works of which the merit depends on their instantaneous effect, the most hasty judgment is likely to be the best."

"The effective strength of sects, is not to be ascertained merely by counting heads."

"The effect of violent animosities between parties has always been an indifference to the general welfare and honour of the state. A politician, where factions run high, is interested not for the whole people, but for his own section of it. The rest are, in his view, strangers, enemies, or rather pirates. The strongest aversion which he can feel to any foreign power is the ardour of friendship, when compared with the loathing which he entertains towards those domestic foes with whom he is cooped up in a narrow space, with whom he lives in a constant interchange of petty injuries and insults, and from whom, in the day of their success, he has to expect severities far beyond any that a conqueror from a distant country would inflict. Thus, in Greece, it was a point of honour for a man to cleave to his party against his country. No aristocratical citizen of Santos or Corcyra would have hesitated to call in the aid of Lacedæmon. The multitude, on the contrary, looked everywhere to Athens. In the Italian States of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, from the same cause, no man was so much a Pisan or a Florentine as a Ghibeline or a Guelf. It may be doubted whether there was a single individual who would have scrupled to raise his party from a state of depression by opening the gates of his native city to a French or an Arragonese force. The Reformation, dividing almost every European country into two parts, produced similar effects. The Catholic was too strong for the Englishman, the Huguenot for the Frenchman. The Protestant statesmen of Scotland and France called in the aid of Elizabeth; and the Papists of the League brought a Spanish army into the very heart of France. The commotions to which the French Revolution gave rise were followed by the same consequences. The Republicans in every part of Europe were eager to see the armies of the National Convention and the Directory appear among them, and exulted in defeats which distressed and humbled those whom they considered as their worst enemies, their own rulers. The princes and nobles of France, on the other hand, did their utmost to bring foreign invaders to Paris. A very short time has elapsed since the Apostolical party in Spain invoked, too successfully, the support of strangers."

"The emancipation of the press produced a great and salutary change. The best and wisest men in the ranks of the opposition now assumed an office which had hitherto been abandoned to the unprincipled or the hot-headed. Tracts against the government were written in a style not misbecoming statesmen and gentlemen, and even the compositions of the lower and fiercer class of malecontents became somewhat less brutal and less ribald than formerly."

"The effect of slavery is completely to dissolve the connection which naturally exists between the higher and lower classes of free citizens. The rich spend their wealth in purchasing and maintaining slaves. There is no demand for the labour of the poor; the fable of Menenius ceases to be applicable; the belly communicates no nutriment to the members: there is an atrophy in the body politic. The two parties, therefore, proceed to extremities utterly unknown in countries where they have mutually need of each other. In Rome the oligarchy was too powerful to be subverted by force; and neither the tribunes nor the popular assemblies, though constitutionally omnipotent, could maintain a successful contest against men who possessed the whole property of the state. Hence the necessity for measures tending to unsettle the whole frame of society and to take away every motive of industry; the abolition of debts, and the agrarian laws,—propositions absurdly condemned by men who do not consider the circumstances from which they sprung. They were the desperate remedies of a desperate disease. In Greece the oligarchical interest was not in general so deeply looted as in Rome. The multitude, therefore, often redressed by force grievances which, at Rome, were commonly attacked under the forms of the constitution. They drove out or massacred the rich, and divided their property. If the superior union or military skill of the rich rendered them victorious, they took measures equally violent, disarmed all in whom they could not confute, often slaughtered great numbers, and occasionally expelled the whole commonalty from the city, and remained, with their slaves, the sole inhabitants."

"The effect of violent dislike between groups has always created an indifference to the welfare and honor of the state."

"The errors of both parties arise from an ignorance or a neglect of fundamental principles of political science. The writers on one side imagine popular government to be always a blessing; Mr. Mitford omits no opportunity of assuring us that it is always a curse. The fact is, that a good government, like a good coat, is that which fits the body for which it is designed. A man who, upon abstract principles, pronounces a constitution to be good, without an exact knowledge of the people who are to be governed by it, judges as absurdly as a tailor who should measure the Belvedere Apollo for the clothes of all his customers. The demagogues who wished to see Portugal a republic, and the wise critics who revile the Virginians for not having instituted a peerage, appear equally ridiculous to all men of sense and candour."

"The English Bible - a book which, if everything else in our language should perish, would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power."

"The essence of slavery, the circumstance which makes slavery the worst of all social evils, is not in our opinion this, that the master has a legal right to certain services from the slave, but this, that the master has a legal right to enforce the performance of those services without having recourse to the tribunals. He is a judge in his own cause. He is armed with the powers of a magistrate for the protection of his own private interest against the person who owes him service. Every other judge quits the bench as soon as his own cause is called on. The judicial authority of the master begins and ends with cases in which he has a direct stake. The moment that a master is really deprived of this authority, the moment that his right to service really becomes, like his right to money which he has lent, a mere civil right, which he can enforce only by a civil action, the peculiarly odious and malignant evils of slavery disappear at once."

"The first effect of this great revolution was, as Bacon most justly observed [De Augmentis, lib. i.], to give for a time an undue importance to the mere graces of style. The new breed of scholars, the Aschams and Buchanans, nourished with the finest compositions of the Augustan age, regarded with loathing the dry, crabbed, and barbarous diction of respondents and opponents. They were far less studious about the matter of their writing than about the manner. They succeeded in reforming Latinity; but they never even aspired to effect a reform in philosophy."

"The fact is that common observers reason from the progress of the experimental sciences to that of the imitative arts. The improvement of the former is gradual and slow. Ages are spent in collecting materials, ages more in separating and combining them. Even when a system has been formed, there is still something to add, to alter, or to reject. Every generation enjoys the use of a vast hoard bequeathed to it by antiquity, and transmits that hoard, augmented by fresh acquisitions, to future ages. In these pursuits, therefore, the first speculators lie under great disadvantages, and, even when they fail, are entitled to praise. Their pupils, with far inferior intellectual powers, speedily surpass them in actual attainments. Every girl who has read Mrs. Marcet’s little dialogues on Political Economy could teach Montaigne or Walpole many lessons in finance. Any intelligent man may now, by resolutely applying himself for a few years to mathematics, learn more than the great Newton knew after half a century of study and meditation."

"The excellence of these works is in a great measure the result of two peculiarities which the critics of the French school consider as defects,—from the mixture of tragedy and comedy, and from the length and extent of the action. The former is necessary to render the drama a just representation of a world in which the laughers and the weepers are perpetually jostling each other,—in which every event has its serious and ludicrous side. The latter enables us to form an intimate acquaintance with characters with which we could not possibly become familiar during the few hours to which the unities restrict the poet. In this respect the works of Shakespeare, in particular, are miracles of art. In a piece which may be read aloud in three hours we see a character unfold all its recesses to us. We see it change with the change of circumstances. The petulant youth rises into the politic and warlike sovereign. The profuse and courteous philanthropist sours into a hater and scorner of his kind. The tyrant is altered, by the chastening of affliction, into a pensive moralist. The veteran general, distinguished by coolness, sagacity, and self-command, sinks under a conflict between love strong as death and jealousy cruel as the grave. The brave and loyal subject passes, step by step, to the extremities of human depravity. We trace his progress from the first dawnings of unlawful ambition to the cynical melancholy of his impenitent remorse. Yet in these pieces there are no unnatural transitions. Nothing is omitted; nothing is crowded. Great as are the changes, narrow as is the compass within which they are exhibited, they shock us as little as the gradual alterations of those familiar faces which we see every evening and every morning. The magical skill of the poet resembles that of the Dervise in the Spectator, who condensed all the events of seven years into the single moment during which the king held his head under the water."

"The first victory of good taste is over the bombast and conceits which deform such times as these. But criticism is still in a very imperfect state. What is accidental is for a long time confounded with what is essential. General theories are drawn from detached facts. How many hours the action of a play may be allowed to occupy,—how many similes an Epic Poet may introduce into his first book,—whether a piece, which is acknowledged to have a beginning and an end, may not be without a middle, and other questions as puerile as these, formerly occupied, the attention of men of letters in France, and even in this country. Poets in such circumstances as these exhibit all the narrowness and feebleness of the criticism by which their manner has been fashioned. From outrageous absurdity they are preserved by their timidity. But they perpetually sacrifice nature and reason to arbitrary canons of taste. In their eagerness to avoid the mala prohibita of a foolish code, they are perpetually rushing on the mala in se. Their great predecessors, it is true, were as bad critics as themselves, or perhaps worse, but those predecessors, as we have attempted to show, were inspired by a faculty independent of criticism, and, therefore, wrote well while they judged ill."

"The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen."

"The first works of the imagination are, as we have said, poor and rude, not from the want of genius, but from the want of materials. Phidias could have done nothing with an old tree and a fish-bone, or Homer with the language of New Holland."

"The gallery in which the reporters sit has become a fourth estate of the realm."

"The general propositions of Aristotle are valuable. But the merit of the superstructure bears no proportion to that of the foundation. This is partly to be ascribed to the character of the philosopher, who, though qualified to do all that could be done by the resolving and combining powers of the understanding, seems not to have possessed much of sensibility or imagination. Partly, also, it may be attributed to the deficiency of materials. The great works of genius which then existed were not either sufficiently numerous or sufficiently varied to enable any man to form a perfect code of literature. To require that a critic should conceive classes of composition which had never existed, and then investigate their principles, would be as unreasonable as the demand of Nebuchadnezzar, who expected his magicians first to tell him his dream and then to interpret it."

"The Glorious Constitution, again, has meant everything in turn: the Habeas Corpus Act, the Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, the Test Act, the Repeal of the Test Act. There has not been for many years a single important measure which has not been unconstitutional with its opponents, and which its supporters have not maintained to be agreeable to the true spirit of the constitution. Is it easier to ascertain what is for the greatest happiness of the human race than what is the constitution of England? If not, the greatest happiness principle will be what the principles of the Constitution are,—a thing to be appealed to by everybody, and understood by everybody in the sense which suits him best."

"The genie had at first vowed that he would confer wonderful gifts on any one who should release him from the casket in which he was imprisoned; and during a second period he had vowed a still more splendid reward. But being still disappointed, he next vowed to grant no other favour to his liberator than to choose what death he should suffer. Even thus, a people who have been enslaved and oppressed for some years are most grateful to their liberators; but those who are set free after very long slavery are not unlikely to tear their liberators to pieces."

"The great cause of revolutions is this, that while nations move onward, constitutions stand still."

"The glory of the National Assembly [of France] is this, that they were in truth, what Mr. Burke called them in austere irony, the ablest architects of ruin that ever the world saw. They were utterly incompetent to perform any work which required a discriminating eye and a skilful hand. But the work which was then to be done was a work of devastation. They had to deal with abuses so horrible and so deeply rooted that the highest political wisdom could scarcely have produced greater good to mankind than was produced by their fierce and senseless temerity. Demolition is undoubtedly a vulgar task; the highest glory of the statesman is to construct. But there is a time for everything,—a time to set up, and a time to pull down. The talents of revolutionary lenders and those of the legislator have equally their use and their season. It is the natural, the almost universal, law that the age of insurrections and proscriptions shall precede the age of good government, of temperate liberty, and liberal order. And how should it be otherwise? It is not in swaddling-bands that we learn to walk. It is not in the dark that we learn to distinguish colours. It is not under oppression that we learn how to use freedom."

"The greatest happiness principle of Mr. Bentham is included in the Christian morality, and, to our thinking, it is there exhibited in an infinitely more sound and philosophical form than in the Utilitarian speculations. For in the New Testament it is neither an identical proposition nor a contradiction in terms; and, as laid down by Mr. Bentham, it must be either the one or the other. Do as you would be done by: Love your neighbour as yourself: these are the precepts of Jesus Christ. Understood in an enlarged sense, these precepts are, in fact, a direction to every man to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number. But this direction would be utterly unmeaning, as it actually is in Mr. Bentham’s philosophy, unless it were accompanied by a sanction. In the Christian scheme, accordingly, it is accompanied by a sanction of immense force. To a man whose greatest happiness in this world is inconsistent with the greatest happiness of the greatest number is held out the prospect of an infinite happiness hereafter, from which he excludes himself by wronging his fellow-creatures here."

"The great productions of Athenian and Roman genius are indeed still what they were. But, though their positive value is unchanged, their relative value, when compared with the whole mass of mental wealth possessed by mankind, has been constantly falling. They were the intellectual all of our ancestors. They are but a part of our treasures. Over what tragedy could Lady Jane Grey have wept, over what comedy could she have smiled, if the ancient dramatists had not been in her library? A modern reader may make shift without Œdipus and Medea, while he possesses Othello and Hamlet. If he knows nothing of Pyrgopolynices and Thraso, he is familiar with Bobadil, and Bessus, and Pistol, and Parolles. If he cannot enjoy the delicious irony of Plato, he may find some compensation in that of Pascal. If he is shut out from Nephelococcygia, he may take refuge in Liliput. We are guilty, we hope, of no irreverence towards those great nations to which the human race owes art, science, taste, civil and intellectual freedom, when we say that the stock bequeathed by them to us has been so carefully improved that the accumulated interest now exceeds the principal. We believe that the books which have been written in the languages of western Europe during the last two hundred and fifty years—translations from the ancient languages of course included—are of greater value than all the books which at the beginning of that period were extant in the world. With the modern languages of Europe English women are at least as well acquainted as English men. When, therefore, we compare the acquirements of Lady Jane Grey with those of an accomplished young woman of our own time, we have no hesitation in awarding the superiority to the latter. We hope that our readers will pardon this digression. It is long; but it can hardly be called unseasonable, if it tends to convince them that they are mistaken in thinking that the great-great-grandmothers of their great-great-grandmothers were superior women to their sisters and wives."

"The Greek drama, on the model of which the Samson was written, sprang from the Ode. The dialogue was ingrafted on the chorus, and naturally partook of its character. The genius of the greatest of the Athenian dramatists co-operated with the circumstances under which tragedy made its first appearance. Æschylus was, head and heart, a lyric poet. In his time, the Greeks had far more intercourse with the East than in the days of Homer; and they had not yet acquired that immense superiority in war, in science, and in the arts, which, in the following generation, led them to treat the Asiatics with contempt. From the narrative of Herodotus it should seem that they still looked up, with the veneration of disciples, to Egypt and Assyria. At this period, accordingly, it was natural that the literature of Greece should be tinctured with the Oriental style. And that style we think is discernible in the works of Pindar and Æschylus. The latter often reminds us of the Hebrew writers. The book of Job, indeed, in conduct and diction, bears a considerable resemblance to some of his dramas. Considered as plays, his works are absurd; considered as choruses, they are above all praise. If, for instance, we examine the address of Clytæmnestra to Agamemnon on his return, or the description of the seven Argive chiefs, by the principles of dramatic writing, we shall instantly condemn them as monstrous. But if we forget the characters, and think only of the poetry, we shall admit that it has never been surpassed in energy and magnificence. Sophocles made the Greek drama as dramatic as was consistent with its original form. His portraits of men have a sort of similarity; but it is the similarity not of a painting, but of a bas-relief. It suggests a resemblance, but it does not produce an illusion. Euripides attempted to carry the reform further. But it was a task far beyond his powers, perhaps beyond any powers. Instead of correcting what was bad, he destroyed what was excellent. He substituted crutches for stilts, bad sermons for good odes."

"The highest kind of poetry is, in a great measure, independent of those circumstances which regulate the style of composition in prose. But with that inferior species of poetry which succeeds to it the case is widely different. In a few years the good sense and good taste which had weeded out affectation from moral and political treatises would, in the natural course of things, have effected a similar reform in the sonnet and the ode. The rigour of the victorious sectaries had relaxed. A dominant religion is never ascetic. The government connived at theatrical representations. The influence of Shakespeare was once more felt. But darker days were approaching. A foreign yoke was to be imposed on our literature. Charles, surrounded by the companions of his long exile, returned to govern a nation which ought never to have cast him out or never to have received him back. Every year which he had passed among strangers had rendered him more unfit to rule his countrymen. In France he had seen the refractory magistracy humbled, and royal prerogative, though exercised by a foreign priest in the name of a child, victorious over all opposition. This spectacle naturally gratified a prince to whose family the opposition of Parliaments had been so fatal. Politeness was his solitary good quality. The insults which he had suffered in Scotland taught him to prize it. The effeminacy and apathy of his disposition fitted him to excel in it. The elegance and vivacity of the French manners fascinated him. With the political maxims and the social habits of his favourite people he adopted their taste in composition, and, when seated on the throne, soon rendered it fashionable, partly by direct patronage, but still more by that contemptible policy which for a time made England the last of the nations, and raised Louis the Fourteenth to a height of power and fame such as no French sovereign had ever before attained. It was to please Charles that rhyme was first introduced into our plays. Thus, a rising blow, which would at any time have been mortal, was dealt to the English Drama, then just recovering from its languishing condition. Two detestable manners, the indigenous and the imported, were now in a state of alternate conflict and amalgamation. The bombastic meanness of the new style was blended with the ingenious absurdity if the old; and the mixture produced something which the world had never before seen, and which we hope it will never see again,—something by the side of which the worst nonsense of all other ages appears to advantage,—something which those who have attempted to caricature it have, against their will, been forced to flatter,—of which the tragedy of Bayes is a very favourable specimen. What Lord Dorset observed to Edward Howard might have been addressed to almost all his contemporaries,—"

"The History [of Florence, by Machiavelli] does not appear to be the fruit of much industry or research. It is unquestionably inaccurate. But it is elegant, lively, and picturesque, beyond any other in the Italian language. The reader, we believe, carries away from it a more vivid and a more faithful impression of the national character and manners than from more correct accounts. The truth is, that the book belongs rather to ancient than to modern literature. It is in the style, not of Davila and Clarendon, but of Herodotus and Tacitus. The classical histories may almost be called romances founded in fact. The relation is, no doubt, in all its principal points, strictly true. But the numerous little incidents which heighten the interest, the words, the gestures, the looks, are evidently furnished by the imagination of the author. The fashion of later times is different. A more exact narrative is given by the writer. It may be doubted whether more exact notions are conveyed to the reader. The best portraits are perhaps those in which there is a slight mixture of caricature; and we are not certain that the best histories are not those in which a little of the exaggeration of fictitious narrative is judiciously employed. Something is lost in accuracy; but much is gained in effect. The fainter lines are neglected; but the great characteristic features are imprinted on the mind forever."

"The highest intellects, like the tops of mountains, are the first to catch and to reflect the dawn."

"The history of Catholicism strikingly illustrates these observations. During the last seven centuries the public mind of Europe has made constant advances in every department of secular knowledge. But in religion we can trace no constant progress. The ecclesiastical history of that long period is a history of movement to and fro. Four times since the authority of the Church of Rome was established in Western Christendom has the human intellect risen up against her yoke. Twice that Church remained completely victorious. Twice she came forth from the conflict bearing the marks of cruel wounds, but with the principle of life still strong within her. When we reflect on the tremendous assaults which she has survived, we find it difficult to conceive in what way she is to perish."

"The history of England is emphatically the history of progress."

"The history of Monmouth would alone suffice to refute the imputation of inconstancy which is so frequently thrown on the common people. The common people are sometimes inconstant; for they are human beings. But that they are inconstant as compared with the educated classes, with aristocracies, or with princes, may be confidently denied. It would be easy to name demagogues whose popularity has remained undiminished while sovereigns and parliaments have withdrawn their confidence from a long succession of statesmen…. The charge which may with justice be brought against the common people is, not that they are inconstant, but that they almost invariably choose their favourite so ill that their constancy is a vice and not a virtue."

"The history of every literature with which we are acquainted confirms, we think, the principles which we have laid down. In Greece we see the imaginative school of poetry gradually fading into the critical. Æschylus and Pindar were succeeded by Sophocles, Sophocles by Euripides, Euripides by the Alexandrian versifiers. Of these last Theantus alone has left compositions which deserve to be read. The splendour and grotesque fairy-land of the Old Comedy, rich with such gorgeous hues, peopled with such fantastic shapes, and vocal alternately with the sweetest peals of music and the loudest bursts of elvish laughter, disappeared forever. The masterpieces of the New Comedy are known to us by Latin translations of extraordinary merit. From these translations, and from the expressions of the ancient critics, it is clear that the original compositions were distinguished by grace and sweetness, that they sparkled with wit and abounded with pleasing sentiment, but that the creative power was gone. Julius Cæsar called Terence a half Menander,—a sure proof that Menander was not a quarter Aristophanes."

"The history of eloquence at Athens is remarkable. From a very early period great speakers had flourished there. Pisistratus and Themistocles are said to have owed much of their influence to their talents for debate. We learn, with more certainty, that Pericles was distinguished by extraordinary oratorical powers. The substance of some of his speeches is transmitted to us by Thucydides; and that excellent writer has doubtless faithfully reported the general line of his arguments. But the manner, which in oratory is at least of as much consequence as the matter, was of no importance to his narration. It is evident that he has not attempted to preserve it. Throughout his work, every speech on every subject, whatever may have been the character of the dialect of the speaker, is in exactly the same form. The grave king of Sparta, the furious demagogue of Athens, the general encouraging his army, the captive supplicating for his life, all are represented as speakers in one unvaried style,—a style, moreover, wholly unfit for oratorical purposes. His mode of reasoning is singularly elliptical,—in reality most consecutive, yet in appearance often incoherent. His meaning, in itself sufficiently perplexing, is compressed into the fewest possible words. His great fondness for antithetical expressions has not a little conduced to this effect. one must have observed how much more the sense is condensed in the verses of Pope and his imitators, who never ventured to continue the same clause from couplet to couplet, than in those of poets who allow themselves that license. Every artificial division which is strongly marked, and which frequently recurs, has the same tendency. The natural and perspicuous expression which spontaneously rises to the mind will often refuse to accommodate itself to such a form. It is necessary either to expand it into weakness, or to compress it into almost impenetrable density. The latter is generally the choice of an able man, and was assuredly the choice of Thucydides."

"The inductive method has been practiced ever since the beginning of the world by every human being. It is constantly practiced by the most ignorant clown, by the most thoughtless school-boy, by the very child at the breast. That method leads the clown to the conclusion that if he sows barley he shall not reap wheat. By that method the school-boy learns that a cloudy day is the best for catching trout. The very infant, we imagine, is led by induction to expect milk from his mother or nurse, and none from his father."

"The immoral English writers of the seventeenth century are indeed much less excusable than those of Greece and Rome. But the worst English writings of the seventeenth century are decent compared with much that has been bequeathed to us by Greece and Rome. Plato, we have little doubt, was a much better man than Sir George Etherege. But Plato has written things at which Sir George Etherege would have shuddered. Buckhurst and Sedley, even in those wild orgies at the lock in Bow Street for which they were pelted by the rabble, and fined by the Court of King’s Bench, would never have dared to hold such discourse as passed between Socrates and Phædrus on that fine summer day under the plane-tree, while the fountain warbled at their feet and the cicadas chirped overhead. If it be, as we think it is, desirable that an English gentleman should be well informed touching the government and the manners of little commonwealths which both in place and time are far removed from us, whose independence has been more than two thousand years extinguished, whose language has not been spoken for ages, and whose ancient magnificence is attested only by a few broken columns and friezes, much more must it be desirable that he should be intimately acquainted with the history of the public mind of his own country, and with the causes, the nature, and the extent of those revolutions of opinion and feeling which during the last two centuries have alternately raised and depressed the standard of our national morality. And knowledge of this sort is to be very sparingly gleaned from Parliamentary debates, from state papers, and from the works of grave historians. It must either not be acquired at all, or it must be acquired by the perusal of the light literature which has at various periods been fashionable."

"The knowledge of the theory of logic has no tendency whatever to make men good reasoners."

"The instruction derived from history thus written would be of a vivid and practical character. It would be received by the imagination as well as by the reason. It would be not merely traced on the mind, but branded into it. Many truths, too, would be learned, which can be learned in no other manner. As the history of states is generally written, the greatest and most momentous revolutions seem to come upon them like supernatural inflictions, without warning or cause. But the fact is, that such revolutions are almost always the consequences of moral changes which have gradually passed on the mass of the community, and which originally proceed far before their progress is indicated by any public measure. An intimate knowledge of the domestic history of nations is therefore absolutely necessary to the prognosis of political events. A narrative deficient in this respect is as useless as a medical treatise which should pass by all the symptoms attendant on the early stage of a disease and mention only what occurs when the patient is beyond the reach of remedies."

"The history of the successors of Theodosius bears no small analogy to that of the successors of Aurungzebe. But perhaps the fall of the Carlovingians furnishes the nearest parallel to the fall of the Moguls. Charlemagne was scarcely interred when the imbecility and the disputes of his descendants began to bring contempt on themselves and destruction on their subjects. The wide dominion of the Franks was severed into a thousand pieces. Nothing more than a nominal dignity was left to the abject heirs of an illustrious name: Charles the Bold, and Charles the Fat, and Charles the Simple. Fierce invaders, differing from each other in race, language, and religion, flocked, as if by concert, from the farthest corners of the earth, to plunder provinces which the government could no longer defend. The pirates of the Northern Sea extended their ravages from the Elbe to the Pyrenees, and at length fixed their seat in the rich valley of the Seine. The Hungarian, in whom the trembling monks fancied that they recognized the Gog or Magog of prophecy, carried back the plunder of the cities of Lombardy to the depths of the Pannonian forests. The Saracen ruled in Sicily, desolated the fertile plains of Campania, and spread terror even to the walls of Rome. In the midst of these sufferings a great internal change passed upon the empire. The corruption of death began to ferment into new forms of life. While the great body, as a whole, was torpid and passive, every separate member began to feel with a sense and to move with an energy all its own. Just here, in the most barren and dreary tract of European history, all feudal privileges, all modern nobility, take their source. It is to this point that we trace the power of those princes who, nominally vassals, but really independent, long governed, with the titles of dukes, marquesses, and counts, almost every part of the dominions which had obeyed Charlemagne."

"The latter manner be practices most frequently in his tragedies, the former in his comedies. The comic characters are, without mixture, loathsome and despicable. The men of Etherege and Vanbrugh are bad enough. Those of Smollett are perhaps worse. But they do not approach to the Celadons, the Wildbloods, the Woodalls, and the Rhodophils of Dryden. The vices of these last are set off by a certain fierce hard impudence, to which we know nothing comparable. Their love is the appetite of beasts; their friendship the confederacy of knaves. The ladies seem to have been expressly created to form helps meet for such gentlemen. In deceiving and insulting their old fathers they do not, perhaps, exceed the license which, by immemorial prescription, has been allowed to heroines. But they also cheat at cards, rob strong boxes, put up their favours to auction, betray their friends, abuse their rivals in the style of Billingsgate, and invite their lovers in the language of the Piazza. These, it must be remembered, are not the valets and waiting-women, the Mascarilles and Nerines, but the recognized heroes and heroines who appear as the representatives of good society, and who, at the end of the fifth act, marry and live very happily ever after. The sensuality, baseness, and malice of their natures is unredeemed by any quality of a different description,—by any touch of kindness,—or even by any honest burst of hearty hatred and revenge. We are in a world where there is no humanity, no veracity, no sense of shame,—a world for which any good-natured man would gladly take in exchange the society of Milton’s devils. But as soon as we enter the regions of Tragedy we find a great change. There is no lack of fine sentiment there. Metastasio is surpassed in his own department. Scuderi is out-scuderied. We are introduced to people whose proceedings we can trace to no motive,—of whose feelings we can form no more idea than of a sixth sense. We have left a race of creatures whose love is as delicate and affectionate as the passion which an alderman feels for a turtle. We find ourselves among beings whose love is a purely disinterested emotion,—a loyalty extending to passive obedience,—a religion, like that of the Quietists, unsupported by any sanction of hope or fear. We see nothing but despotism without power, and sacrifices without compensation."

"The last moments of Addison were perfectly serene. His interview with his son-in-law is universally known. See, he said, how a Christian can die! The piety of Addison was, in truth, of a singularly cheerful character. The feeling which predominates in all his devotional writings is gratitude. God was to him the all-wise and all-powerful friend who had watched over his cradle with more than maternal tenderness; who had listened to his cries before they could form themselves in prayer; who had preserved his youth from the snares of vice; who had made his cup run over with worldly blessings; who had doubled the value of those blessings by bestowing a thankful heart to enjoy them and dear friends to partake them; who had rebuked the waves of the Ligurian gulf, had purified the autumnal air of the Campagna, and had restrained the avalanches of Mount Cenis. Of the Psalms, his favourite was that which represents the Ruler of all things under the endearing image of a shepherd, whose crook guides the flock safe through gloomy and desolate glens, to meadows well watered and rich with herbage. On that goodness to which he ascribed all the happiness of his life he relied in the hour of death with the love which casteth out fear."