Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

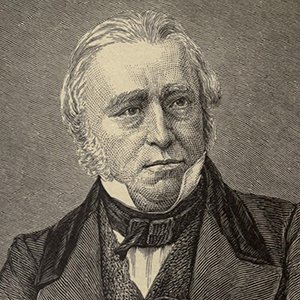

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"It is not difficult to elude both the horns of this dilemma. We will recur to the analogous art of portrait-painting. Any man with eyes and hands may be taught to take a likeness. The process, up to a certain point, is merely mechanical. If this were all, a man of talents might justly despise the occupation. But we could mention portraits which are resemblances,—but not mere resemblances; faithful,—but much more than faithful; portraits which condense into one point of time, and exhibit at a single glance, the whole history of turbid and eventful lives—in which the eye seems to scrutinize us, and the mouth to command us—in which the brow menaces, and the lip almost quivers with scorn—in which every wrinkle is a comment on some important transaction. The account which Thucydides has given of the retreat from Syracuse is, among narratives, what Vandyke’s Lord Strafford is among paintings."

"It is not necessary for me in this place to go through the arguments which prove beyond dispute that on the security of property civilization depends; that where property is insecure no climate however delicious, no soil however fertile, no conveniences for trade and navigation, no natural endowments of body or of mind, can prevent a nation from sinking into barbarism; that where, on the other hand, men are protected in the enjoyment of what has been created by their industry and laid up by their self-denial, society will advance in arts and in wealth notwithstanding the sterility of the earth and the inclemency of the air, notwithstanding heavy taxes and destructive wars."

"It is odd that the last twenty-five years which have witnessed the greatest progress ever made in physical science — the greatest victories ever achieved by mind over matter — should have produced hardly a volume that will be remembered in 1900."

"It is only in a refined and speculative age that a polity is constructed on system. In rude societies the progress of government resembles the progress of language and of versification. Rude societies have language, and often copious and energetic language: but they have no scientific grammar, no definitions of nouns and verbs, no names for declensions, moods, tenses, and voices. Rude societies have versification, and often versification of great power and sweetness: but they have no metrical canons; and the minstrel whose numbers, regulated solely by his ear, are the delight of his audience, would himself be unable to say of how many dactyls and trochees each of his lines consists. As eloquence exists before syntax, and song before prosody, so government may exist in a high degree of excellence long before the limits of legislative, executive, and judicial power have been traced with precision."

"It is remarkable that the practice of separating the two ingredients of which history is composed has become prevalent on the Continent as well as in this country. Italy has already produced a historical novel, of high merit and of still higher promise. In France the practice has been carried to a length somewhat whimsical. M. Sismondi publishes a grave and stately history of the Merovingian Kings, very valuable, and a little tedious. He then sends forth as a companion to it a novel, in which he attempts to give a lively representation of characters and manners. This course, as it seems to us, has all the disadvantages of a division of labour, and none of its advantages. We understand the expediency of keeping the functions of cook and coachman distinct. The dinner will be better dressed, and the horses better managed. But where the two situations are united, as in the Maître Jacques of Molière, we do not see that the matter is much mended by the solemn form with which the pluralist passes from one of his employments to the other."

"It is possible to be below flattery as well as above it."

"It is said that the hasty and rapacious Kneller used to send away the ladies who sate to him as soon as he had sketched their faces, and to paint the figures and hands from his housemaid. It was much in the same way that Walpole portrayed the minds of others. He copied from the life only those glaring and obvious peculiarities which could not escape the most superficial observation. The rest of the canvas he filled up, in a careless dashing way, with knave and fool, mixed in such proportions as pleased Heaven. What a difference between these daubs and the masterly portraits of Clarendon!"

"It is scarcely necessary to say that such speeches could never have been delivered. They are perhaps among the most difficult passages in the Greek language, and would probably have been scarcely more intelligible to an Athenian auditor than to a modern reader. Their obscurity was acknowledged by Cicero, who was as intimate with the literature and language of Greece as the most accomplished of its natives, and who seems to have held a respectable rank among the Greek authors. Their difficulty to a modern reader lies, not in the words, but in the reasoning. A dictionary is of far less use in studying them than a clear head and a close attention to the context. They are valuable to the scholar as displaying beyond almost any other compositions the powers of the finest of languages: they are valuable to the philosopher as illustrating the morals and manners of a most interesting age: they abound in just thought and energetic expression. But they do not enable us to form any accurate opinion on the merits of the early Greek orators."

"It is proposed that for every vacancy in the civil service four candidates shall be named; and the best candidate selected by examination. We conceive that under this system the persons sent out will he young men above par, young men superior either in talents or in diligence to the mass. It is said, I know, that examinations in Latin, in Greek, and in mathematics are no tests of what men will prove to be in life. I am perfectly aware that they are not infallible tests; but that they are tests I confidently maintain. Look at every walk of life, at this house, at the other house, at the Bar, at the Bench, at the Church, and see whether it be not true that those who attain high distinction in the world were generally men who were distinguished in their academic career. Indeed, Sir, this objection would prove far too much even for those who use it. It would prove that there is no use at all in education. Why should we put boys out of their way? Why should we force a lad who would much rather fly a kite or trundle a hoop to learn his Latin Grammar? Why should we keep a young man to his Thucydides or his Laplace when he would much rather be shooting? Education would be mere useless torture if at two or three and twenty a man who had neglected his studies were exactly on a par with a man who had applied himself to them, exactly as likely to perform all the offices of public life with credit to himself and with advantage to society. Whether the English system of education be good or bad is not now the question. Perhaps I may think that too much time is given to the ancient languages and to the abstract sciences. But what then? Whatever be the languages, whatever be the sciences, which it is in any age or country the fashion to teach, the persons who become the greatest proficients in those languages and those sciences will generally be the flower of the youth, the most acute, the most industrious, the most ambitious of honourable distinctions. If the Ptolemaic system were taught at Cambridge instead of the Newtonian, the senior wrangler would nevertheless be in general a superior man to the wooden spoon. If instead of learning Greek we learned the Cherokee, the man who understood the Cherokee best, who made the most correct and melodious Cherokee verses, who comprehended most accurately the effect of the Cherokee particles, would generally be a superior man to him who was destitute of these accomplishments. If astrology were taught at our Universities, the young man who cast nativities best would generally turn out a superior man. If alchemy were taught, the young man who showed most activity in the pursuit of the philosopher’s stone would generally turn out a superior man."

"It is singular that, in such an art, Pitt, a man of splendid talents, of great fluency, of great boldness, a man whose whole life was passed in parliamentary conflict, a man who, during several years, was the leading minister of the Crown in the House of Commons, should never have attained to high excellence. He spoke without premeditation; but his speech followed the course of his own thoughts, and not the course of the previous discussion. He could, indeed, treasure up in his memory some detached expression of a hostile orator, and make it the text for lively ridicule or solemn reprehension. Some of the most celebrated bursts of his eloquence were called forth by an unguarded word, a laugh, or a cheer. But this was the only sort of reply in which he appears to have excelled. He was perhaps the only great English orator who did not think it any advantage to have the last word, and who generally spoke by choice before his most formidable opponents. His merit was almost entirely rhetorical. He did not succeed either in exposition or in refutation; but his speeches abounded with lively illustrations, striking apothegms, well-told anecdotes, happy allusions, passionate appeals. His invective and sarcasm were terrific. Perhaps no English orator was ever so much feared."

"It is the age that forms the man, not the man that forms the age. Great minds do indeed react on the society which has made them what they are, but they only pay with interest what they have received."

"It is some consolation to reflect that the critical school of poetry improves as the science of criticism improves; and that the science of criticism, like every other science, is constantly tending towards perfection. As experiments are multiplied, principles are better understood."

"It is the nature of the Devil of tyranny to tear and rend the body which he leaves. Are the miseries of continued possession less horrible than the struggles of the tremendous exorcism?"

"It is the same with the characters of men. Here, too, the variety passes all enumeration. But the cases in which the deviation from the common standard is striking and grotesque, are very few. In one mind avarice predominates; in another, pride; in a third, love of pleasure; just as in one countenance the nose is the most marked feature, while in others the chief expression lies in the brow, or in the lines of the mouth. But there are very few countenances in which nose, brow, and mouth do not contribute, though in unequal degrees, to the general effect; and so there are very few characters in which one overgrown propensity makes all others utterly insignificant."

"It is the character of such revolutions that we always see the worst of them at first. Till men have been some time free, they know not how to use their freedom. The natives of wine countries are generally sober. In climates where wine is a rarity, intemperance abounds. A newly-liberaled people may be compared to a northern army encamped on the Rhine or the Xeres. It is said that when soldiers in such a situation first find themselves able to indulge without restraint in such a rare and expensive luxury, nothing is to be seen but intoxication. Soon, however, plenty teaches discretion; and, after wine has been for a few months their daily fare, they become more temperate than they had ever been in their own country. In the same manner, the final and permanent fruits of liberty are wisdom, moderation, and mercy. Its immediate effects are often atrocious crimes, conflicting errors, scepticism on points the most clear, dogmatism on points the most mysterious. It is just at this crisis that its enemies love to exhibit it. They pull down the scaffolding from the half-finished edifice; they point to the flying dust, the falling bricks, the comfortless rooms, the frightful irregularity of the whole appearance; and then ask in scorn where the promised splendour and comfort is to be found. If such miserable sophisms were to prevail, there would never be a good house or a good government in the world."

"It is true that he professed himself a supporter of toleration. Every sect clamours for toleration when it is down. We have not the smallest doubt that when Bonner was in the Marshalsea he thought it a very hard thing that a man should be locked up in a gaol for not being able to understand the words This is my body in the same way with the lords of the council. It would not be very wise to conclude that a beggar is full of Christian charity because he assures you that God will reward you if you give him a penny; or that a soldier is humane because he cries out lustily for quarter when a bayonet is at his throat. The doctrine which, from the very first origin of religious dissensions, has been held by bigots of all sects, when condensed into a few words and stripped of rhetorical disguise, is simply this: I am in the right, and you are in the wrong. When you are the stronger, you ought to tolerate me; for it is your duty to tolerate truth. But when I am the stronger, I shall persecute you; for it is my duty to persecute error."

"It may be doubted whether any compositions which have ever been produced in the world are equally perfect in their kind with the great Athenian orations. Genius is subject to the same laws which regulate the production of cotton and molasses. The supply adjusts itself to the demand. The quantity may be diminished by restrictions and multiplied by bounties. The singular excellence to which eloquence attained at Athens is mainly to be attributed to the influence which it exerted there. In turbulent times, under a constitution purely democratic, among a people educated exactly to that point at which men are most susceptible of strong and sudden impressions, acute but not sound reasoners, warm in their feelings, unfixed in their principles, and passionate admirers of fine composition, oratory received such encouragement as it has never since obtained."

"It is very reluctantly that Seneca can be brought to confess that any philosopher had ever paid the smallest attention to anything that could possibly promote what vulgar people would consider as the well-being of mankind. He labours to clear Democritus from the disgraceful imputation of having made the first arch, and Anacharsis from the charge of having contrived the potter’s wheel. He is forced to own that such a thing might happen; and it may also happen, he tells us, that a philosopher may be swift of foot. But it is not in his character of philosopher that he either wins a race or invents a machine. No, to be sure. The business of a philosopher was to declaim in praise of poverty, with two millions sterling out at usury, to meditate epigrammatic conceits about the evils of luxury, in gardens which moved the envy of sovereigns, to rant about liberty, while fawning on the insolent and pampered freedmen of a tyrant, to celebrate the divine beauty of virtue with the same pen which had just before written a defense of the murder of a mother by a son."

"It is true that, after the Revolution, when the Parliament began to make inquisition for the innocent blood which had been shed by the last Stuarts, a feeble attempt was made to defend the lawyers who had been accomplices in the murder of Sir Thomas Armstrong, on the ground that they had only acted professionally. The wretched sophism was silenced by the execrations of the House of Commons. Things will never be well done, said Mr. Foley, till some of that profession be made examples. We have a new sort of monsters in the world, said the younger Hampden, haranguing a man to death. These I call blood-hounds. Sawyer is very criminal, and guilty of this murder. I speak to discharge my conscience, said Mr. Galloway. I will not have the blood of this man at my door. Sawyer demanded judgment against him and execution. I believe him guilty of the death of this man. Do what you will with him. If the profession of the law, said the elder Hampden, gives a man authority to murder at this rate, it is the interest of all men to rise and exterminate that profession. Nor was this language held only by unlearned country gentlemen. Sir William Williams, one of the ablest and most unscrupulous lawyers of the age, took the same view of the case. He had not hesitated, he said, to take part in the prosecution of the Bishops, because they were allowed counsel. But he maintained that, where the prisoner was not allowed counsel, the Counsel for the Crown was bound to exercise a discretion, and that every lawyer who neglected this distinction was a betrayer of the law. But it was unnecessary to cite authority. It is known to everybody who has ever looked into a court of quarter-sessions that lawyers do exercise a discretion in criminal cases; and it is plain to every man of common sense that if they did not exercise such a discretion they would be a more hateful body of men than those bravos who used to hire out their stilettoes in Italy."

"It might be amusing to institute a comparison between one of the profoundly learned men of the thirteenth century and one of the superficial students who will frequent our library. Take the great philosopher of the time of Henry the Third of England, or Alexander the Third of Scotland, the man renowned all over the island, and even as far as Italy and Spain, as the first of astronomers and chemists. What is his astronomy? He is a firm believer in the Ptolemaic system. He never heard of the law of gravitation. Tell him that the succession of day and night is caused by the turning of the earth on its axis. Tell him that in consequence of this motion the polar diameter of the earth is shorter than the equatorial diameter. Tell him that the succession of summer and winter is caused by the revolution of the earth round the sun. If he does not set you down as an idiot, he lays an information against you before the Bishop, and has you burned for an heretic. To do him justice, however, if he is ill informed on these points, there are other points on which Newton and Laplace were mere children when compared with him. He can cast your nativity. He knows what will happen when Saturn is in the House of Life, and what will happen when Mars is in conjunction with the Dragon’s Tail. He can read in the stars whether an expedition will be successful, whether the next harvest will be plentiful, which of your children will be fortunate in marriage, and which will be lost at sea. Happy the State, happy the family, which is guided by the counsels of so profound a man! And what but mischief, public and private, can we expect from the temerity and conceit of sciolists who know no more about the heavenly bodies than what they have learned from Sir John Herschel’s beautiful little volume? But, to speak seriously, is not a little truth better than a great deal of falsehood? Is not the man who in the evenings of a fortnight has acquired a correct notion of the solar system a more profound astronomer than a man who has passed thirty years in reading lectures about the primum mobile and in drawing schemes of horoscopes?"

"It seems that the creative faculty and the critical faculty cannot exist together in their highest perfection."

"It may be laid down as an almost universal rule that good poets are bad critics. Their minds are under the tyranny of ten thousand associations imperceptible to others. The worst writer may easily happen to touch a spring which is connected in their minds with a long succession of beautiful images. They are like the gigantic slaves of Aladdin,—gifted with matchless power, but bound by spells so mighty that when a child whom they could have crushed touched a talisman, of whose secret they were ignorant, they immediately became his vassals. It has more than once happened to me to see minds graceful and majestic as the Titania of Shakespeare bewitched by the charms of an ass’s head, bestowing on it the fondest caresses, and crowning it with the sweetest flowers."

"It may be laid as a universal rule that a government which attempts more than it ought will perform less."

"It was in this way that our ancestors reasoned, and that some people in our time still reason, about the Catholics. A Papist believes himself bound to obey the Pope. The Pope has issued a bull deposing Queen Elizabeth. Therefore every Papist will treat her grace as an usurper. Therefore every Papist is a traitor. Therefore every Papist ought to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. To this logic we owe some of the most hateful laws that ever disgraced our history."

"It seems to me that when I look back on our history I can discern a great party which has, through many generations, preserved its identity; a party often depressed, never extinguished; a party which, though often tainted with the faults of the age, has always been in advance of the age; a party which, though guilty of many errors and some crimes, has the glory of having established our civil and religious liberties on a firm foundation: and of that party I am proud to be a member. It was that party which on the great question of monopolies stood up against Elizabeth. It was that party which in the reign of James the First organized the earliest parliamentary opposition, which steadily asserted the privileges of the people, and wrested prerogative after prerogative from the Crown. It was that party which forced Charles the First to relinquish the ship-money. It was that party which destroyed the Star Chamber and the High Commission Court. It was that party which, under Charles the Second, carried the Habeas Corpus Act, which effected the Revolution, which passed the Toleration Act, which broke the yoke of a foreign Church in your country, and which saved Scotland from the fate of unhappy Ireland. It was that party which reared and maintained the constitutional throne of Hanover against the hostility of the Church and of the landed aristocracy of England. It was that party which opposed the war with America and the war with the French Republic; which imparted the blessings of our free Constitution to the Dissenters; and which, at a later period, by unparalleled sacrifices and exertions, extended the same blessings to the Roman Catholics. To the Whigs of the seventeenth century we owe it that we have a House of Commons. To the Whigs of the nineteenth century we owe it that the House of Commons has been purified. The abolition of the slave-trade, the abolition of colonial slavery, the extension of popular education, the mitigation of the rigour of the penal code, all, all were effected by that party; and of that party, I repeat, I am a member. I look with pride on all that the Whigs have done for the cause of human freedom and of human happiness. I see them now hard pressed, struggling with difficulties, but still fighting the good fight. At their head I see men who have inherited the spirit and the virtues, as well as the blood, of old champions and martyrs of freedom. To those men I propose to attach myself. Delusion may triumph; but the triumphs of delusion are but for a day. We may be defeated; but our principles will gather fresh strength from defeats. Be that, however, as it may, my part is taken. While one shred of the old banner is flying, by that banner will I at least be found."

"It was not only by the efficacy of the restraints imposed on the royal prerogative that England was advantageously distinguished from most of the neighbouring countries. A peculiarity equally important, though less noticed, was the relation in which the nobility stood here to the community. There was a strong hereditary aristocracy: but it was of all hereditary aristocracies the least insolent and exclusive. It had none of the invidious character of a caste. It was constantly receiving members from the people, and constantly sending down members to mingle with the people. Any gentleman might become a peer. The younger son of a peer was but a gentleman. Grandsons of peers yielded precedence to newly-made knights. The dignity of knighthood was not beyond the reach of any man who could by diligence and thrift realize a good estate, or who could attract notice by his valour in a battle or a siege. It was regarded as no disparagement for the daughter of a Duke, nay, of a royal Duke, to espouse a distinguished commoner. Thus. Sir John Howard married the daughter of Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk. Sir Richard Pole married the Countess of Salisbury, daughter of George, Duke of Clarence. Good blood was indeed held in high respect: but between good blood and the privileges of peerage there was, most fortunately for our country, no necessary connection. Pedigrees as long, and scutcheons as old, were to be found out of the House of Lords as in it. There were new men who bore the highest titles. There were untitled men well known to be descended from knights who had broken the Saxon ranks at Hastings and scaled the walls of Jerusalem. There were Bohuns, Mowbrays, De Veres, nay, kinsmen of the House of Plantagenet, with no higher addition than that of Esquire, and with no civil privileges beyond those enjoyed by every farmer and shopkeeper. There was therefore here no line like that which in some other countries divided the patrician from the plebeian. The yeoman was not inclined to murmur at dignities to which his own children might rise. The grandee was not inclined to insult a class into which his own children must descend."

"It was the same with our fathers in the time of the Great Civil War. We are by no means unmindful of the great debt which mankind owes to the Puritans of that time, the deliverers of England, the founders of the American Commonwealth. But in the day of their power those men committed one great fault, which left deep and lasting traces in the national character and manners. They mistook the end and over-rated the force of government. They determined, not merely to protect religion and public morals from insult, an object for which the civil sword, in discreet hands, may be beneficially employed, but to make the people committed to their rule truly devout. Yet, if they had only reflected on events which they had themselves witnessed and in which they had themselves borne a great part, they would have seen what was likely to be the result of their enterprise. They had lived under a government which, during a long course of years, did all that could be done, by lavish bounty and by rigorous punishment, to enforce conformity to the doctrine and discipline of the Church of England. No person suspected of hostility to that church had the smallest chance of obtaining favour at the court of Charles. Avowed dissent was punished by imprisonment, by ignominious exposure, by cruel mutilations, and by ruinous fines. And the event had been that the church had fallen, and had in its fall dragged down with it a monarchy which had stood six hundred years. The Puritan might have learned, if from nothing else, yet from his own recent victory, that governments which attempt things beyond their reach are likely not merely to fail, but to produce an effect directly the opposite of that which they contemplate as desirable."

"It seems to us, also, to be the height of absurdity to employ civil disabilities for the propagation of an opinion, and then to shrink from employing other punishments for the same purpose. For nothing can be clearer than that, if you punish at all, you ought to punish enough. The pain caused by punishment is pure unmixed evil, and never ought to be inflicted except for the sake of some good. It is mere foolish cruelty to provide penalties which torment the criminal without preventing the crime. Now, it is possible, by sanguinary persecution unrelentingly inflicted, to suppress opinions. In this way the Albigenses were put down. In this way the Lollards were put down. In this way the fair promise of the Reformation was blighted in Italy and Spain. But we may safely defy Mr. Gladstone to point out a single instance in which the system which he recommends has succeeded."

"It was a fashion among those Greeks and Romans who cultivated rhetoric as an art, to compose epistles and harangues in the names of eminent men. Some of these counterfeits are fabricated with such exquisite taste and skill that it is the highest achievement of criticism to distinguish them from originals. Others are so feebly and rudely executed that they can hardly impose on an intelligent school-boy. The best specimen which has come down to us is perhaps the oration of Marcellus, such an imitation of Tully’s eloquence as Tully himself would have read with wonder and delight. The worst specimen is perhaps a collection of letters purporting to have been written by that Phalaris who governed Agrigentum more than 500 years before the Christian era. The evidence, both internal and external, against the genuineness of these letters is overwhelming. When, in the fifteenth century, they emerged, in company with much that was far more valuable, from their obscurity, they were pronounced spurious by Politian, the greatest scholar of Italy, and by Erasmus, the greatest scholar on our side of the Alps. In truth, it would be as easy to persuade an educated Englishman that one of Johnson’s Ramblers was the work of William Wallace as to persuade a man like Erasmus that a pedantic exercise, composed in the trim and artificial Attic of the time of Julian, was a dispatch written by a crafty and ferocious Dorian who roasted people alive many years before there existed a volume of prose in the Greek language."

"It would be amusing to make a digest of the irrational laws which bad critics have framed for the government of poets. First in celebrity and in absurdity stand the dramatic unities of place and time. No human being has ever been able to find anything that could, even by courtesy, be called an argument for these unities, except that they have been deduced from the general practice of the Greeks. It requires no very profound examination to discover that the Greek dramas, often admirable as compositions, are, as exhibitions of human character and human life, far inferior to the English plays of the age of Elizabeth. Every scholar knows that the dramatic part of the Athenian tragedies was at first subordinate to the lyrical part. It would, therefore, have been little less than a miracle if the laws of the Athenian stage had been found to suit plays in which there was no chorus. All the greatest masterpieces of the dramatic art have been composed in direct violation of the unities, and could never have been composed if the unities had not been violated. It is clear, for example, that such a character as that of Hamlet could never have been developed within the limits to which Alfieri confined himself. Yet such was the reverence of literary men during the last century for these unities that Johnson, who, much to his honour, took the opposite side, was, as he says, frightened at his own temerity, and afraid to stand against the authorities which might be produced against him."

"It was thus in our country. The line which bounded the royal prerogative, though sufficiently clear, had not everywhere been drawn with accuracy and distinctness."

"It would be, on the most selfish view of the case, far better for us that the people of India were well governed and independent of us, than ill governed and subject to us; that they were ruled by their own kings, but wearing our broadcloth, and working with our cutlery, than that they were performing their salams to English collectors and English magistrates, but were too ignorant to value, or too poor to buy, English manufactures. To trade with civilized men is infinitely more profitable than to govern savages."

"James [I. and VI.] was always boasting of his skill in what he called kingcraft; and yet it is hardly possible even to imagine a course more directly opposed to all the rules of kingcraft than that which he followed. The policy of wise rulers has always been to disguise strong acts under popular forms. It was thus that Augustus and Napoleon established absolute monarchies, while the public regarded them merely as eminent citizens invested with temporary magistracies. The policy of James was the direct reverse of theirs. He enraged and alarmed his parliament by constantly telling them that they held their privileges merely during his pleasure, and that they had no more business to inquire what he might lawfully do than what the Deity might lawfully do. Yet he quailed before them, abandoned minister after minister to their vengeance, and suffered them to tease him into acts directly opposed to his strongest inclinations. Thus the indignation excited by his claims and the scorn excited by his concessions went on growing together."

"Johnson decided literary questions like a lawyer, not like a legislator. He never examined foundations where a point was already ruled. His whole code of criticism rested on pure assumption, for which he sometimes quoted a precedent or an authority, but rarely troubled himself to give a reason drawn from the nature of things."

"Lady Bacon was doubtless a lady of highly, cultivated mind after the fashion of her age. But we must not suffer ourselves to be deluded into the belief that she and her sisters were more accomplished women than many who are now living. On this subject there is, we think, much misapprehension. We have often heard men who wish, as almost all men of sense wish, that women should be highly educated, speak with rapture of the English ladies of the sixteenth century, and lament that they can find no modern damsels resembling those fair pupils of Ascham and Aylmer who compared over their embroidery the styles of Isocrates and Lysias, and who, while the horns were sounding and the dogs in full cry, sat in the lonely oriel, with eyes riveted to that immortal page which tells how meekly and bravely the first great martyr of intellectual liberty took the cup from his weeping gaoler. But surely these complaints have very little foundation. We would by no means disparage the ladies of the sixteenth century or their pursuits. But we conceive that those who extol them at the expense of the women of our time forget one very obvious and very important circumstance. In the time of Henry the Eighth and Edward the Sixth, a person who did not read Greek and Latin could read nothing, or next to nothing. The Italian was the only modern language which possessed anything that could be called a literature. All the valuable books then extant in all the vernacular dialects of Europe would hardly have filled a single shelf. England did not yet possess Shakespeare’s plays and the Fairy Queen, nor France Montaigne’s Essays, nor Spain Don Quixote. In looking round a well-furnished library, how many English or French books can we find which were extant when Lady Jane Grey and Queen Elizabeth received their education? Chaucer, Gower, Froissart, Comines, Rabelais, nearly complete the list. It was therefore absolutely necessary that a woman should be uneducated or classically educated. Indeed, without a knowledge of one of the ancient languages no person could then have any clear notion of what was passing in the political, the literary, or the religious world. The Latin was in the sixteenth century all and more than all that the French was in the eighteenth."

"Just such is the manner in which nine readers out of ten judge of a book. They are ashamed to dislike what men who speak as having authority declare to be good. At present, however contemptible a poem or a novel may be, there is not the least difficulty in procuring favourable notices of it from all sorts of publications, daily, weekly, and monthly. In the mean time, little or nothing is said on the other side. The author and the publisher are interested in crying up the book. Nobody has any very strong interest in crying it down. Those who are best fitted to guide the public opinion think it beneath them to expose mere nonsense, and comfort themselves by reflecting that such popularity cannot last. This contemptuous levity has been carried too far. It is perfectly true that reputations which have been forced into an unnatural bloom fade almost as soon as they have expanded; nor have we any apprehensions that puffing will ever raise any scribbler to the rank of a classic."

"Just such is the feeling which a man of liberal education naturally entertains towards the great minds of former ages. The debt which he owes to them is incalculable. They have guided him to truth. They have filled his mind with noble and graceful images. They have stood by him in all vicissitudes, comforters in sorrow, nurses in sickness, companions in solitude. These friendships are exposed to no danger from the occurrences by which other attachments are weakened or dissolved. Time glides on; fortune is inconstant; tempers are soured; bonds which seemed indissoluble are daily sundered by interest, by emulation, or by caprice. But no such cause can affect the silent converse which we hold with the highest of human intellects. That placid intercourse is disturbed by no jealousies or resentments. These are the old friends who are never seen with new faces, who are the same in wealth and in poverty, in glory and in obscurity. With the dead there is no rivalry. In the dead there is no change. Plato is never sullen. Cervantes is never petulant. Demosthenes never comes unseasonably. Dante never stays too long. No difference of political opinion can alienate Cicero. No heresy can excite the honor of Bossuet."

"Let us overleap two or three hundred years, and contemplate Europe at the commencement of the eighteenth century. Every free constitution, save one, had gone down. That of England had weathered the danger, and was riding in full security. In Denmark and Sweden, the kings had availed themselves of the disputes which raged between the nobles and the commons, to unite all the powers of government in their own hands. In France, the institution of the States was only mentioned by lawyers as a part of the ancient theory of their government. It slept a deep sleep, destined to be broken by a tremendous waking. No person remembered the sittings of the three orders, or expected ever to see them renewed. Louis the Fourteenth had imposed on his parliament a patient silence of sixty years. His grandson, after the War of the Spanish Succession, assimilated the constitution of Aragon to that of Castile, and extinguished the last feeble remains of liberty in the Peninsula. In England, on the other hand, the Parliament was infinitely more powerful than it had ever been. Not only was its legislative authority fully established; but its right to interfere, by advice almost equivalent to command, in every department of the executive government, was recognized. The appointment of ministers, the relations with foreign powers, the conduct of a war or a negotiation, depended less on the pleasure of the Prince than on that of the two Houses."

"Like them, he kept his mind continually fixed on an Almighty Judge and an eternal reward. And hence he acquired their contempt of external circumstances, their fortitude, their tranquillity, their inflexible resolution. But not the coolest sceptic or the most profane scoffer was more perfectly free from the contagion of their frantic delusions, their savage manners, their ludicrous jargon, their scorn of science, and their aversion to pleasure. Hating tyranny with a perfect hatred, he had nevertheless all the estimable and ornamental qualities which were almost entirely monopolized by the party of the tyrant. There was none who had a stronger sense of the value of literature, a finer relish for every elegant amusement, or a more chivalrous delicacy of honour and love. Though his opinions were democratic, his tastes and his associations were such as harmonize best with monarchy and aristocracy. He was under the influence of all the feelings by which the gallant Cavaliers were misled. But of those feelings he was the master and not the slave. Like the hero of Homer, he enjoyed all the pleasures of fascination; but he was not fascinated. He listened to the song of the Syrens; yet he glided by without being seduced to their fatal shore. He tasted the cup of Circe; but he bore about him a sure antidote against the effects of its bewitching sweetness. The illusions which captivated his imagination never impaired his reasoning powers. The statesman was proof against the splendour, the solemnity, and the romance which enchanted the poet."

"Laws exist in vain for those who have not the courage and the means to defend them."

"Language, the machine of the poet, is best fitted for his purpose in its rudest state. Nations, like individuals, first perceive, and then abstract. They advance from particular images to general terms. Hence the vocabulary of an enlightened society is philosophical, that of a half-civilized people is poetical."

"Let us pass to astronomy. This was one of the sciences which Plato exhorted his disciples to learn, but for reasons far removed from common habits of thinking. Shall we set down astronomy, says Socrates, among the subjects of study? [Plato’s Republic, Book VII.] I think so, answers his young friend Glaucon: to know something about the seasons, the months, and the years is of use for military purposes, as well as for agriculture and navigation. It amuses me, says Socrates, to see how afraid you are lest the common herd of men should accuse you of recommending useless studies. He then proceeds, in that pure and magnificent diction which, as Cicero said, Jupiter would use if Jupiter spoke Greek, to explain that the use of astronomy is not to add to the vulgar comforts of life, but to assist in raising the mind to the contemplation of things which are to be perceived by the pure intellect alone. The knowledge of the actual motions of the heavenly bodies Socrates considers as of little value. The appearances which make the sky beautiful at night are, he tells us, like the figures which a geometrician draws on the sand, mere examples, mere helps to feeble minds. We must get beyond them; we must neglect them; we must attain to an astronomy which is as independent of the actual stars as geometrical truth is independent of the lines of an ill-drawn diagram. This is, we imagine, very nearly, if not exactly, the astronomy which Bacon compared to the ox of Prometheus [De Augmentis, Lib. 3, cap. 4], a sleek, well-shaped hide, stuffed with rubbish, goodly to look at, but containing nothing to eat. He complained that astronomy had, to its great injury, been separated from natural philosophy, of which it was one of the noblest provinces, and annexed to the domain of mathematics. The world stood in need, he said, of a very different astronomy, of a living astronomy [Astronomia viva], of an astronomy which should set forth the nature, the motion, and the influences of the heavenly bodies, as they really are."

"Let us suppose that Lord Clarendon, instead of filling hundreds of folio pages with copies of state papers, in which the same assertions and contradictions are repeated till the reader is overpowered with weariness, had condescended to be the Boswell of the Long Parliament. Let us suppose that he had exhibited to us the wise and lofty self-government of Hampden, leading while he seemed to follow, and propounding unanswerable arguments in the strongest forms with the modest air of an inquirer anxious for information; the delusions which misled the noble spirit of Vane; the coarse fanaticism which concealed the yet loftier genius of Cromwell, destined to control a mutinous army and a factious people, to abase the flag of Holland, to arrest the victorious arms of Sweden, and to hold the balance firm between the rival monarchies of France and Spain. Let us suppose that he had made his Cavaliers and Roundheads talk in their own style; that he had reported some of the ribaldry of Rupert’s pages, and some of the cant of Harrison and Fleetwood. Would not his work in that case have been more interesting? Would it not have been more accurate?"

"Logicians may reason about abstractions. But the great mass of men must have images. The strong tendency of the multitude in all ages and nations to idolatry can be explained on no other principle. The first inhabitants of Greece, there is reason to believe, worshipped one invisible Deity. But the necessity of having something more definite to adore produced, in a few centuries, the innumerable crowds of Gods and Goddesses. In like manner the ancient Persians thought it impious to exhibit the Creator under a human form. Yet even these transferred to the sun the worship which, in speculation, they considered due only to the Supreme Mind. The history of the Jews is the record of a continued struggle between pure Theism, supported by the most terrible sanctions, and the strangely fascinating desire of having some visible and tangible object of adoration. Perhaps none of the secondary causes which Gibbon has assigned for the rapidity with which Christianity spread over the world, while Judaism scarcely ever acquired a proselyte, operated more powerfully than this feeling. God, the uncreated, the incomprehensible, the invisible, attracted few worshippers. A philosopher might admire so noble a conception; but the crowd turned away in disgust from words which presented no image to their minds. It was before Deity embodied in a human form, walking among men, partaking of their infirmities, leaning on their bosoms, weeping over their graves, slumbering in the manger, bleeding on the cross, that the prejudices of the Synagogue, and the doubts of the Academy, and the pride of the Portico, and the fasces of the Lictor, and the swords of thirty legions, were humbled in the dust."

"Macaulay's minute on education arguing for the use of English in India"

"Mannerism is pardonable, and is sometimes even agreeable, when the manner, though vicious, is natural. Few readers, for example, would be willing to part with the mannerism of Milton or of Burke. But a mannerism which does not sit easy on the mannerist, which has been adopted on principle, and which can be sustained only by constant effort, is always offensive. And such is the mannerism of Johnson."

"Longinus seems to have had great sensibility, but little discrimination. He gives us eloquent sentences, but no principles. It was happily said that Montesquieu ought to have changed the name of his book from L’Esprit des Lois to L’Esprit sur les Lois. In the same manner the philosopher of Palmyra ought to have entitled his famous work not Longinus on the Sublime, but The Sublimities of Longinus. The origin of the sublime is one of the most curious and interesting subjects of inquiry that can occupy the attention of a critic. In our own country it has been discussed with great ability, and, I think, with very little success, by Burke and Dugald Stewart. Longinus dispenses himself from all investigations of this nature by telling his friend Terentianus that he already knows everything that can be said upon the question. It is to be regretted that Terentianus did not impart some of his knowledge to his instructor; for from Longinus we learn only that sublimity means height—or elevation. This name, so commodiously vague, is applied indifferently to the noble prayer of Ajax in the Iliad, and to a passage of Plato about the human body, as full of conceits as an ode of Cowley. Having no fixed standard, Longinus is right only by accident. He is rather a fancier than a critic."

"Many causes predisposed the public mind to a change. The study of a great variety of ancient writers, though it did not give a right direction to philosophical research, did much towards destroying that blind reverence for authority which had prevailed when Aristotle ruled alone. The rise of the Florentine sect of Platonists, a sect to which belonged some of the finest minds of the fifteenth century, was not an unimportant event. The mere substitution of the Academic for the Peripatetic philosophy would indeed have done little good. But anything was better than the old habit of unreasoning servility. It was something to have a choice of tyrants. A spark of freedom, as Gibbon has justly remarked, was produced by this collision of adverse servitude."

"Many men, said Mr. Milton, have floridly and ingeniously compared anarchy and despotism; but they who so amuse themselves do but look at separate parts of that which is truly one great whole. Each is the cause and the effect of the other; the evils of either are the evils of both. Thus do states move on in the same eternal cycle, which, from the remotest point, brings them back again to the same sad starting-point: and, till both those who govern and those who obey shall learn and mark this great truth, men can expect little through the future, as they have known little through the past, save vicissitudes of extreme evils, alternately producing and produced."

"Many noble monuments which have since been destroyed still retained their pristine magnificence; and travellers, to whom Livy and Sallust were unintelligible, might gain from the Roman aqueducts and temples some faint notion of Roman history. The dome of Agrippa, still glittering with bronze, the mausoleum of Adrian, not yet deprived of its columns and statues, the Flavian amphitheatre, not yet degraded into a quarry, told to the rude English pilgrim some part of the story of that great civilized world which had passed away. The islanders returned with awe deeply impressed on their half-opened minds, and told the wondering inhabitants of the hovels of London and York that, near the grave of Saint Peter, a mighty race, now extinct, had piled up buildings which would never be dissolved till the judgment day. Learning followed in the train of Christianity. The poetry and eloquence of the Augustan age was assiduously studied in Mercian and Northumbrian monasteries. The names of Bede and Alcuin were justly celebrated throughout Europe. Such was the state of our country when, in the ninth century, began the last great migration of the northern barbarians."