Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

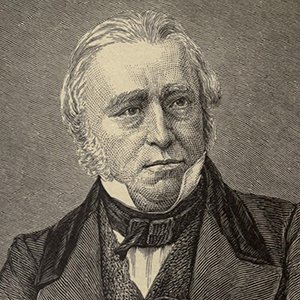

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"Many politicians of our time are in the habit of laying it down as a self-evident proposition that no people ought to be free until they are fit to use their freedom. The maxim is worthy of the fool in the old story who resolved not to go into the water till he had learned to swim. If men are to wait for liberty till they become wise and good in slavery, they may indeed wait forever."

"Men are never so likely to settle a question rightly as when they discuss it freely. A government can interfere in discussion only by making it less free than it would otherwise be. Men are most likely to form just opinions when they have no other wish than to know the truth, and are exempt from all influence either of hope or fear. Government, as government, can bring nothing but the influence of hopes and fears to support its doctrines. It carries on controversy, not with reasons, but with threats and bribes. If it employs reasons, it does so, not in virtue of any powers which belong to it as a government. Thus, instead of a contest between argument and argument, we have a contest between argument and force. Instead of a contest in which truth, from the natural constitution of the human mind, has a decided advantage over falsehood, we have a contest in which truth can be victorious only by accident."

"Men naturally sympathize with the calamities of individuals; but they are inclined to look on a fallen party with contempt rather than with pity."

"Mellifluous streams, that watered all the schools."

"Miss Burney did for the English novel what Jeremy Collier did for the English drama; and she did it in a better way. She first showed that a tale might be written in which both the fashionable and the vulgar life of London might be exhibited with great force and with broad comic humour, and which yet should not contain a single line inconsistent with rigid morality, or even with virgin delicacy. She took away the reproach which lay on a most useful and delightful species of composition. She vindicated the right of her sex to an equal share in a fair and noble province of letters. Several accomplished women have followed in her track. At present, the novels which we owe to English ladies form no small part of the literary glory of our country. No class of works is more honourably distinguished by fine observation, by grace, by delicate wit, by pure moral feeling. Several among the successors of Madame D’Arblay have equalled her; two, we think, have surpassed her. But the fact that she has been surpassed gives her an additional claim to our respect and gratitude; for, in truth, we owe to her not only Evelina, Cecilia, and Camilla, but also Mansfield Park and The Absentee."

"Men of great conversational powers almost universally practice a sort of lively sophistry and exaggeration which deceives for the moment both themselves and their auditors."

"Mr. Bentham has no new motive to furnish his disciples with. He has talents sufficient to effect anything that can be effected. But to induce men to act without an inducement is too much even for him. He should reflect that the whole vast world of morals cannot be moved unless the mover can obtain some stand for his engines beyond it. He acts as Archimedes would have done if he had attempted to move the earth by a lever fixed on the earth. The action and reaction neutralize each other. The artist labours, and the world remains at rest. Mr. Bentham can only tell us to do something which we have always been doing, and should still have continued to do, if we had never heard of the greatest happiness principle,—or else to do something which we have no conceivable motive for doing, and therefore shall not do. Mr. Bentham’s principle is at best no more than the golden rule of the Gospel without its sanction. Whatever evils, therefore, have existed in societies in which the authority of the Gospel is recognized may, a fortiori, as it appears to us, exist in societies in which the Utilitarian principle is recognized. We do not apprehend that it is more difficult for a tyrant or a persecutor to persuade himself and others that in putting to death those who oppose his power or differ from his opinions he is pursuing the greatest happiness, than that he is doing as he would be done by. But religion gives him a motive for doing as he would be done by: and Mr. Bentham furnishes him no motive to induce him to promote the general happiness. If, on the other hand, Mr. Bentham’s principle mean only that every man should pursue his own greatest happiness, he merely asserts what everybody knows, and recommends what everybody does."

"Milton did not strictly belong to any of the classes which we have described. He was not a Puritan. He was not a free thinker. He was not a Royalist. In his character the noblest qualities of every party were combined in harmonious union. From the Parliament and from the Court, from the conventicle and from the Gothic cloister, from the gloomy and sepulchral circles of the Roundheads, and from the Christmas revel of the hospitable Cavalier, his nature selected and drew to itself whatever was great and good, while it rejected all the base and pernicious ingredients by which those finer elements were defiled. Like the Puritans, he lived"

"Mr. Hallam is of opinion that a bill of pains and penalties ought to have been passed; but he draws a distinction less just, we think, than his distinctions usually are. His opinion, so far as we can collect it, is this, that there are almost insurmountable objections to retrospective laws for capital punishment, but that, where the punishment stops short of death, the objections are comparatively trifling. Now, the practice of taking the severity of the penalty into consideration, when the question is about the mode of procedure and the rules of evidence, is no doubt sufficiently common. We often see a man convicted of a simple larceny on evidence on which he would not be convicted of a burglary. It sometimes happens that a jury, when there is strong suspicion, but not absolute demonstration, that an act, unquestionably amounting to murder, was committed by the prisoner before them, will find him guilty of manslaughter. But this is surely very irrational. The rules of evidence no more depend on the magnitude of the interests at stake than the rules of arithmetic. We might as well say that we have a greater chance of throwing a six when we are playing for a penny than when we are playing for a thousand pounds, as that a form of trial which is sufficient for the purposes of justice in a matter affecting liberty and property is insufficient in a matter affecting life. Nay, if a mode of proceeding be too lax for capital cases, it is, a fortiori, too lax for all others; for, in capital cases, the principles of human nature will always afford considerable security. No judge is so cruel as he who indemnifies himself for scrupulosity in cases of blood by license in affairs of smaller importance. The difference in tale on the one side far more than makes up for the difference in weight on the other."

"Mr. Gladstone conceives that the duties of governments are paternal; a doctrine which we shall not believe till he can show us some government which loves its subjects as a father loves a child, and which is as superior in intelligence to its subjects as a father is to a child. He tells us, in lofty though somewhat indistinct language, that Government occupies in moral the place [Greek] in physical science. If government be indeed [Greek] in moral science, we do not understand why rulers should not assume all the functions which Plato assigned to them. Why should they not take away the child from the mother, select the nurse, regulate the school, overlook the playground, fix the hours of labour and of recreation, prescribe what ballads shall be sung, what tunes shall be played, what books shall be read, what physic shall be swallowed? Why should not they choose our wives, limit our expenses, and stint us to a certain number of dishes of meat, of glasses of wine, and of cups of tea? Plato, whose hardihood in speculation was perhaps more wonderful than any other peculiarity of his extraordinary mind, and who shrank from nothing to which his principles led, went this whole length. Mr. Gladstone is not so intrepid. He contents himself with laying down this proposition, that, whatever be the body which in any community is employed to protect the persons and property of men, that body ought also, in its corporate capacity, to profess a religion, to employ its power for the propagation of that religion, and to require conformity to that religion as an indispensable qualification for all civil office. He distinctly declares that he does not in this proposition confine his view to orthodox governments, or even to Christian governments. The circumstance that a religion is false does not, he tells us, diminish the obligation of governors, as such, to uphold it. If they neglect to do so, we cannot, he says, but regard the fact as aggravating the case of the holders of such creed. I do not scruple to affirm, he adds, that, if a Mahometan conscientiously believes his religion to come from God, and to teach divine truth, he must believe that truth to be beneficial, and beneficial beyond all other things to the soul of man; and he must therefore, and ought to, desire its extension, and to use for its extension all proper and legitimate means; and that, if such Mahometan be a prince, he ought to count among those means the application of whatever influence or funds he may lawfully have at his disposal for such purposes."

"More sinners are cursed at not because we despise their sins but because we envy their success at sinning."

"Mr. Montagu maintains that none but the ignorant and unreflecting can think Bacon censurable for anything that he did as counsel for the crown, and that no advocate can justifiably use any discretion as to the party for whom he appears. We will not at present inquire whether the doctrine which is held on this subject by English lawyers be or be not agreeable to reason and morality; whether it be right that a man should, with a wig on his head, and a band round his neck, do for a guinea what without those appendages he would think it wicked and infamous to do for an empire; whether it be right that, not merely believing but knowing a statement to be true, he should do all that can be done by sophistry, by rhetoric, by solemn asseveration, by indignant exclamation, by gesture, by play of features, by terrifying one honest witness, by perplexing another, to cause a jury to think that statement false."

"Mr. Mitford has remarked, with truth and spirit, that any history perfectly written, but especially a Grecian history perfectly written, should be a political institute for all nations. It has not occurred to him that a Grecian history, perfectly written, should also be a complete record of the rise and progress of poetry, philosophy, and the arts. Here his book is extremely deficient. Indeed, though it may seem a strange thing to say of a gentleman who has published so many quartos, Mr. Mitford seems to entertain a feeling bordering on contempt for literary and speculative pursuits. The talents of action almost exclusively attract his notice; and he talks with very complacent disdain of the idle learned. Homer, indeed, he admires; but principally, I am afraid, because he is convinced that Homer could neither read nor write. He could not avoid speaking of Socrates; but he has been far more solicitous to trace his death to political causes, and to deduce from it consequences unfavourable to Athens, and to popular governments, than to throw light on the character and doctrines of the wonderlul man"

"My confidence in my judgment is strengthened when I recollect that I hold that opinion in common with all the greatest lawgivers, statesmen, and political philosophers of all nations and ages, with all the most illustrious champions of civil and spiritual freedom, and especially with those men whose names were once held in the highest veneration by the Protestant Dissenters of England. I might cite many of the most venerable names of the Old World; but I would rather cite the example of that country which the supporters of the Voluntary system here are always recommending to us as a pattern. Go back to the days when the little society which has expanded into the opulent and enlightened commonwealth of Massachusetts began to exist. Our modern Dissenters will scarcely, I think, venture to speak contumeliously of those Puritans whose spirit Laud and his High Commission Court could not subdue, of those Puritans who were willing to leave home and kindred, and all the comforts and refinements of civilized life, to cross the ocean, to fix their abode in forests among wild beasts and wild men, rather than commit the sin of performing in the house of God one gesture which they believed to be displeasing to Him. Did those brave exiles think it inconsistent with civil or religious freedom that the State should take charge of the education of the people? No, Sir: one of the earliest laws enacted by the Puritan colonists was that every township, as soon as the Lord had increased it to the number of fifty houses, should appoint one to teach all children to read and write, and that every township of a hundred houses should set up a grammar school. Nor have the descendants of those who made this law ever ceased to hold that the public authorities were bound to provide the means of public instruction. Nor is this doctrine confined to New England. Educate the people was the first admonition addressed by Penn to the colony which he founded. Educate the people was the legacy of Washington to the nation which he had saved. Educate the people was the unceasing exhortation of Jefferson: and I quote Jefferson with peculiar pleasure, because of all the eminent men that have ever lived, Adam Smith himself not excepted, Jefferson was the one who most abhorred everything like meddling on the part of governments. Yet the chief business of his later years was to establish a good system of State education in Virginia."

"My honourable and learned friend dwells on the claims of the posterity of great writers. Undoubtedly, Sir, it would be very pleasing to see a descendant of Shakespeare living in opulence on the fruits of his great ancestor’s genius. A house maintained in splendour by such a patrimony would be a more interesting and striking object than Blenheim is to us, or than Strathfieldsaye will be to our children. But, unhappily, it is scarcely possible that, under any system, such a thing can come to pass. My honourable and learned friend does not propose that copyright shall descend to the eldest son, or shall be bound up by irrevocable entail. It is to be merely personal property. It is therefore highly improbable that it will descend during sixty years or half that term from parent to child. The chance is that more people than one will have an interest in it. They will in all probability sell it and divide the proceeds. The price which a bookseller will give for it will bear no proportion to the sum which he will afterwards draw from the public if his speculation proves successful. He will give little, if anything, more for a term of sixty years than for a term of thirty or five-and-twenty. The present value of a distant advantage is always small; but where there is great room to doubt whether a distant advantage will be any advantage at all, the present value sinks to almost nothing. Such is the inconstancy of the public taste that no sensible man will venture to pronounce with confidence what the sale of any book published in our days will be in the years between 1890 and 1900. The whole fashion of thinking and writing has often undergone a change in a much shorter period than that to which my honourable and learned friend would extend posthumous copyright. What would have been considered the best literary property in the earlier part of Charles the Second’s reign? I imagine, Cowley’s Poems. Overleap sixty years, and you are in the generation of which Pope asked, Who now reads Cowley? What works were ever expected with more impatience by the public than those of Lord Bolingbroke, which appeared, I think, in 1754? In 1814 no bookseller would have thanked you for the copyright of them all, if you had offered it to him for nothing. What would Paternoster Row give now for the copyright of Hayley’s Triumphs of Temper, so much admired within the memory of people still living? I say, therefore, that from the very nature of literary property it will almost always pass away from an author’s family; and I say that the price given for it will bear a very small proportion to the tax which the purchaser, if his speculation turns out well, will in the course of a long series of years levy on the public."

"Nine-tenths the calamities of the human race are due to the union of high intelligence with low desires."

"Natural theology, then, is not a progressive science. That knowledge of our origin and of our destiny which we derive from revelation is indeed of very different clearness, and of very different importance. But neither is revealed religion of the nature of a progressive science. All Divine truth is, according to the doctrine of the Protestant Churches, recorded in certain books. It is equally open to all who, in any age, can read those books; nor can all the discourses of all the philosophers in the world add a single verse to any of those books. It is plain, therefore, that in divinity there cannot be a progress analogous to that which is constantly taking place in pharmacy, geology, and navigation. A Christian of the fifth century with a Bible is neither better nor worse situated than a Christian of the nineteenth century with a Bible, candour and natural acuteness being supposed equal. It matters not at all that the compass, printing, steam, gas, vaccination, and a thousand other discoveries and inventions, which were unknown in the fifth century, are familiar to the nineteenth. None of these discoveries and inventions has the smallest bearing on the question whether man is justified by faith alone, or whether the invocation of saints is an orthodox practice. It seems to us, therefore, that we have no security for the future against the prevalence of any theological error that ever has prevailed in time past among Christian men. We are confident that the world will never go back to the solar system of Ptolemy; nor is our confidence in the least shaken by the circumstance that even so great a man as Bacon rejected the theory of Galileo with scorn; for Bacon had not all the means of arriving at a sound conclusion which are within our reach, and which secure people who would not have been worthy to mend his pens from falling into his mistakes. But when we reflect that Sir Thomas More was ready to die for the doctrine of transubstantiation, we cannot but feel some doubt whether the doctrine of transubstantiation may not triumph over all opposition. More was a man of eminent talents. He had all the information on the subject that we have, or that, while the world lasts, any human being will have. The text, This is my body, was in his New Testament as it is in ours. The absurdity of the literal interpretation was as great and as obvious in the sixteenth century as it is now. No progress that science has made, or will make, can add to what seems to us the overwhelming force of the argument against the real presence. We are, therefore, unable to understand why what Sir Thomas More believed respecting transubstantiation may not be believed to the end of time by men equal in abilities and honesty to Sir Thomas More. But Sir Thomas More is one of the choice specimens of human wisdom and virtue; and the doctrine of transubstantiation is a kind of proof charge. A faith which stands that test will stand any test. The prophecies of Brothers and the miracles of Prince Hohenlohe sink to trifles in the comparison."

"No picture, then, and no history, can present us with the whole truth: but those are the best pictures and the best histories which exhibit such parts of the truth as most nearly produce the effect of the whole. He who is deficient in the art of selection may, by showing nothing but the truth, produce all the effect of the grossest falsehood. It perpetually happens that one writer tells less truth than another, merely because he tells more truths. In the imitative arts we constantly see this. There are lines in the human face, and objects in landscape, which stand in such relations to each other that they ought either to be all introduced into a painting together or all omitted together. A sketch into which none of them enters may be excellent; but if some are given and others left out, though there are more points of likeness there is less likeness. An outline scrawled with a pen, which seizes the marked features of a countenance, will give a much stronger idea of it than a bad painting in oils. Yet the worst painting in oils that ever hung in Somerset House resembles the original in many more particulars. A bust of white marble may give an excellent idea of a blooming face. Colour the lips and cheeks of the bust, leaving the hair and eyes unaltered, and the similarity, instead of being more striking, will be less so."

"No man who has written so much is so seldom tiresome. In his books there are scarcely any of those passages which, in our school days, we used to call skip. Yet he often wrote on subjects which are generally considered as dull, on subjects which men of great talents have in vain endeavoured to render popular."

"No sophism is too gross to delude minds distempered by party spirit."

"No species of fiction is so delightful to us as the old English drama. Even its inferior productions possess a charm not to be found in any other kind of poetry. It is the most lucid mirror that ever was held up to nature. The creations of the great dramatists of Athens produce the effect of magnificent sculptures, conceived by a mighty imagination, polished with the utmost delicacy, embodying ideas of ineffable majesty and beauty, but cold, pale, and rigid, with no bloom on the cheek, and no speculation in the eye. In all the draperies, the figures, and the faces, in the lovers and the tyrants, the Bacchanals and the Furies, there is the same marble chillness and deadness. Most of the characters of the French stage resemble the waxen gentlemen and ladies in the window of a perfumer, rouged, curled, and bedizened, but fixed in such stiff attitudes, and staring with eyes expressive of such utter unmeaningness, that they cannot produce an illusion for a single moment. In the English plays alone is to be found the warmth, the mellowness, and the reality of painting. We know the minds of the men and women as we know the faces of the men and women of Vandyke."

"No men occupy so splendid a place in history as those who have founded monarchies on the ruins of republican institutions. Their glory, if not of the purest, is assuredly of the most seductive and dazzling kind. In nations broken to the curb, in nations long accustomed to be transferred from one tyrant to another, a man without eminent qualities may easily gain supreme power. The defection of a troop of guards, a conspiracy of eunuchs, a popular tumult, might place an indolent senator or a brutal soldier on the throne of the Roman world. Similar revolutions have often occurred in the despotic state of Asia. But a community which has heard the voice of truth and experienced the pleasures of liberty, in which the merits of statesmen and of systems are freely canvassed, in which obedience is paid, not to persons, but to laws, in which magistrates are regarded not as the lords but as the servants of the public, in which the excitement of a party is a necessary of life, in which political warfare is reduced to a system of tactics,—such a community is not easily reduced to servitude. Beasts of burden may easily be managed by a new master. But will the wild ass submit to the bonds? Will the unicorn serve and abide by the crib? Will leviathan hold out his nostrils to the hook? The mythological conqueror of the East, whose enchantments reduced wild beasts to the tameness of domestic cattle, and who harnessed lions and tigers to his chariot, is but an imperfect type of those extraordinary minds which have thrown a spell on the fierce spirits of nations unaccustomed to control, and have compelled raging factions to obey their reins and swell their triumph. The enterprise, be it good or bad, is one which requires a truly great man. It demands courage, activity, energy, wisdom, firmness, conspicuous virtues, or vices so splendid and alluring as to resemble virtues."

"No writer of British birth is reckoned among the masters of Latin poetry and eloquence. It is not probable that the islanders were at any time generally familiar with the tongue of their Italian rulers. From the Atlantic to the vicinity of the Rhine the Latin has, during many centuries, been predominant. It drove out the Celtic; it was not driven out by the Teutonic; and it is at this day the basis of the French, Spanish, and Portuguese languages. In our island the Latin appears never to have superseded the old Gaelic speech, and could not stand its ground against the German."

"No writers have injured the Comedy of England so deeply as Congreve and Sheridan. Both were men of splendid wit and polished taste. Unhappily, they made all their characters in their own likeness. Their works bear the same relation to the legitimate drama which a transparency bears to a painting. There are no delicate touches, no hues imperceptibly fading into each other: the whole is lighted up with an universal glare. Outlines and tints are forgotten in the common blaze which illuminates all. The flowers and fruits of the intellect abound; but it is the abundance of a jungle, not of a garden, unwholesome, bewildering, unprofitable from its very plenty, rank from its very fragrance. Every fop, every boor, every valet, is a man of wit. The very butts and dupes, Tattle, Witwould, Puff, Acres, outshine the whole Hotel of Rambouillet. To prove the whole system of this school erroneous, it is only necessary to apply the test which dissolved the enchanted Florimel, to place the true by the false Thalia, to contrast the most celebrated characters which have been drawn by the writers of whom we speak with the Bastard in King John, or the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet. It was not surely from want of wit that Shakespeare adopted so different a manner. Benedick and Beatrice throw Mirabel and Millamont into the shade. All the good sayings of the facetious houses of Absolute and Surface might have been clipped from the single character of Falstaff without being missed. It would have been easy for that fertile mind to have given Bardolph and Shallow as much wit as Prince Hal, and to have made Dogberry and Verges retort on each other in sparkling epigrams. But he knew that such indiscriminate prodigality was, to use his own admirable language, from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was, and is, to hold, as it were, the mirror up to nature."

"Nobles by the right of an earlier creation, and priests by the imposition of a mightier hand."

"None of the modes by which a magistrate is appointed, popular election, the accident of the lot, or the accident of birth, affords, as far as we can perceive, much security for his being wiser than any of his neighbours. The chance of his being wiser than all his neighbours together is still smaller."

"Nothing is more amusing and instructive than to observe the manner in which people who think themselves wiser than all the rest of the world fall into snares which the simple good sense of their neighbours detects and avoids. It is one of the principal tenets of the Utilitarians that sentiment and eloquence serve only to impede the pursuit of truth. They therefore affect a quakery plainness, or rather a cynical negligence and impurity, of style. The strongest arguments, when clothed in brilliant language, seem to them so much wordy nonsense. In the mean time they surrender their understandings, with a facility found in no other party, to the meanest and most abject sophisms, provided those sophisms come before them disguised with the externals of demonstration. They do not seem to know that logic has its illusions as well as rhetoric,—that a fallacy may lurk in a syllogism as well as in a metaphor."

"Nothing is more remarkable in the political treatises of Machiavelli than the fairness of mind which they indicate. It appears where the author is in the wrong, almost as strongly as where he is in the right. He never advances a false opinion because it is new or splendid, because he can clothe it in a happy phrase, or defend it by an ingenious sophism. His errors are at once explained by a reference to the circumstances in which he was placed. They evidently were not sought out; they lay in his way and could scarcely be avoided. Such mistakes must necessarily be committed by early speculators in every science. In this respect it is amusing to compare The Prince and the Discourses with the Spirit of Laws. Montesquieu enjoys, perhaps, a wider celebrity than any political writer of modern Europe. Something he doubtless owes to his merit, but much more to his fortune. He had the good luck of a Valentine. He caught the eye of the French nation at the moment when it was waking from the long sleep of political and religious bigotry; and, in consequence, he became a favourite. The English, at that time, considered a Frenchman who talked about constitutional checks and fundamental laws, as a prodigy not less astonishing than the learned pig or the musical infant. Specious but shallow, studious of effect, indifferent to truth, eager to build a system, but careless of collecting those materials out of which alone a sound and durable system can be built, the lively President constructed theories as rapidly and as lightly as card houses, no sooner projected than completed, no sooner completed than blown away, no sooner blown away than forgotten. Machiavelli errs only because his experience, acquired in a very peculiar state of society, could not always enable him to calculate the effect of institutions differing from those of which he had observed the operation. Montesquieu errs, because he has a fine thing to say, and is resolved to say it. If the phenomena which lie before him will not suit his purpose, all history must be ransacked. If nothing established by authentic testimony can be racked or chipped to suit his Procrustean hypothesis, he puts up with some monstrous fable about Siam, or Bantam, or Japan, told by writers compared with whom Lucian and Gulliver were veracious, liars by a double right, as travellers and as Jesuits."

"Not only is it not true that Bacon invented the inductive method, but it is not true that he was the first person who correctly analyzed that method and explained its uses. Aristotle had long before pointed out the absurdity of supposing that syllogistic reasoning could ever conduct men to the discovery of any new principle, had shown that such discoveries must be made by induction, and by induction alone, and had given the history of the inductive process concisely indeed, but with great perspicuity and precision…. But he [Bacon] was the person who first turned the minds of speculative men, long occupied in verbal disputes, to the discovery of new and useful truth; and, by doing so, he at once gave to the inductive method an importance and dignity which had never before belonged to it. He was not the maker of that road; he was not the discoverer of that road; he was not the person who first surveyed and mapped that road. But he was the person who first called the public attention to an inexhaustible mine of wealth, which had been utterly neglected, and which was accessible by that road alone. By doing so he caused that road, which had previously been trodden only by peasants and higglers, to be frequented by a higher class of travellers."

"Nothing except the mint can make money without advertising."

"Nothing, I firmly believe, can now prevent the passing of this noble law, this second Bill of Rights [Murmurs.] Yes, I call it, and the nation calls it, and our posterity will long call it, this second Bill of Rights, this Greater Charter of the Liberties of England. The year 1831 will, I trust, exhibit the first example of the manner in which it behooves a free and enlightened people to purify their polity from old and deeply-seated abuses, without bloodshed, without violence, without rapine, all points freely debated, all the forms of senatorial deliberation punctiliously observed, industry and trade not for a moment interrupted, the authority of law not for a moment suspended. These are things of which we may well be proud. These are things which swell the heart up with a good hope for the destinies of mankind. I cannot but anticipate a long series of happy years; of years during which a parental government will be firmly supported by a grateful nation; of years during which war, if war should be inevitable, will find us an united people; of years pre-eminently distinguished by the progress of arts, by the improvement of laws, by the augmentation of the public resources, by the diminution of the public burdens, by all those victories of peace in which, far more than in any military successes, consists the true felicity of states, and the true glory of statesmen. With such hopes, Sir, and such feelings, I give my cordial assent to the second reading of a bill which I consider as in itself deserving of the warmest approbation, and as indispensably necessary, in the present temper of the public mind, to the repose of the country, and to the stability of the throne."

"Nothing is so useless as a general maxim."

"Nothing is so galling to a people not broken in from the birth as a paternal, or, in other words, a meddling government, a government which tells them what to read, and say, and eat, and drink and wear."

"Now let it be supposed that in aristocratical and monarchical states the desire of wealth and other desires of the same class always tend to produce misgovernment, and that the love of approbation and other kindred feelings always tend to produce good government. Then, if it be impossible, as we have shown that it is, to pronounce generally which of the two classes of motives is the more influential, it is impossible to find out, a priori, whether a monarchical or aristocratical form of government be good or bad."

"Now who will stand on either hand and keep the bridge with me?"

"Now, the only mode in which we can conceive it possible to deduce a theory of government from the principles of human nature is this: we must find out what are the motives which, in a particular form of government, impel rulers to bad measures, and what are those which impel them to good measures: we must then compare the effect of the two classes of motives; and according as we find the one or the other to prevail, we must pronounce the form of government in question good or bad."

"Now, of these objects there is none which men in general seem to desire more than the good opinion of others. The hatred and contempt of the public are generally felt to be intolerable. It is probable that our regard for the sentiments of our fellow-creatures springs, by association, from a sense of their ability to hurt or to serve us. But, be this as it may, it is notorious that, when the habit of mind of which we speak has once been formed, men feel extremely solicitous about the opinions of those by whom it is most improbable, nay, absolutely impossible, that they should ever be in the slightest degree injured or benefited. The desire of posthumous fame and the dread of posthumous reproach and execration are feelings from the influence of which scarcely any man is perfectly free, and which in many men are powerful and constant motives of action."

"Now these are matters in which any man, without any reference to any higher being, or to any future state, is very deeply interested. Every human being, be he idolater, Mahometan, Jew, Papist, Deist, or Atheist, naturally loves life, shrinks from pain, desires comforts which can be enjoyed only in communities where property is secure. To be murdered, to be tortured, to be robbed, to be sold into slavery, to be exposed to the outrages of gangs of foreign banditti calling themselves patriots, these are evidently evils from which men of every religion, and men of no religion, wish to be protected; and therefore it will hardly be disputed that men of every religion, and of no religion, have thus far a common interest in being well governed."

"Obscurity and affectation are the two great faults of style. Obscurity of expression generally springs from confusion of ideas; and the same wish to dazzle, at any cost, which produces affectation in the manner of a writer, is likely to produce sophistry in his reasoning."

"Now, this is the sort of boon which my honourable and learned friend holds out to authors. Considered as a boon to them it is a mere nullity; but considered as an impost on the public it is no nullity, but a very serious and pernicious reality. I will take an example. Dr. Johnson died fifty-six years ago. If the law were what my honourable and learned friend wishes to make it, somebody would now have the monopoly of Dr. Johnson’s works. Who that somebody would be it is impossible to say; but we may venture to guess. I guess, then, that it would have been some bookseller, who was the assign of another bookseller, who was the grandson of a third bookseller, who had bought the copyright from Black Frank, the doctor’s servant and residuary legatee, in 1785 or 1786. Now, would the knowledge that this copyright would exist in 1841 have been a source of gratification to Johnson? Would it have stimulated his exertions? Would it have once drawn him out of his bed before noon? Would it have once cheered him under a fit of the spleen? Would it have induced him to give us one more allegory, one more life of a poet, one more imitation of Juvenal? I firmly believe not. I firmly believe that a hundred years ago, when he was writing out debates for the Gentleman’s Magazine, he would very much rather have had twopence to buy a plate of shin of beef at a cook’s shop underground. Considered as a reward to him, the difference between a twenty years’ and sixty years’ term of posthumous copyright would have been nothing, or next to nothing. But is the difference nothing to us? I can buy Rasselas for sixpence: I might have had to give five shillings for it. I can buy the Dictionary, the entire genuine Dictionary, for two guineas, perhaps for less; I might have had to give five or six guineas for it. Do I grudge this to a man like Dr. Johnson? Not at all. Show me that the prospect of this boon roused him to any vigorous effort, or sustained his spirits under depressing circumstances, and I am quite willing to pay the price of such an object, heavy as that price is. But what I do complain of is that my circumstances are to be worse and Johnson’s none the better; that I am to give five pounds for what to him was not worth a farthing."

"Obstacles unparalleled in any other country which has books must be surmounted by the student who is determined to master the Chinese tongue. To learn to read is the business of half a life. It is easier to become such a linguist as Sir William Jones was than to become a good Chinese scholar. You may count upon your fingers the Europeans whose industry and genius, even when stimulated by the most fervent religious zeal, has triumphed over the difficulties of a language without an alphabet."

"Of the parliamentary eloquence of these celebrated rivals we can judge only by report; and, so judging, we should be inclined to think that, though Shaftesbury was a distinguished speaker, the superiority belongs to Halifax. Indeed, the readiness of Halifax in debate, the extent of his knowledge, the ingenuity of his reasoning, the liveliness of his expression, and the silver clearness and sweetness of his voice, seem to have made the strongest impression on his contemporaries. By Dryden he is described as"

"Of remote countries and past times he [Johnson] talked with wild and ignorant presumption. The Athenians of the age of Demosthenes, he said to Mrs. Thrale, were a people of brutes, a barbarous people. In conversation with Sir Adam Ferguson he used similar language. The boasted Athenians, he said, were barbarians. The mass of every people must be barbarous where there is no printing. The fact was this: he saw that a Londoner who could not read was a very stupid and brutal fellow; he saw that great refinement of taste and activity of intellect were rarely found in a Londoner who had not read much; and, because it was by means of books that people acquired almost all their knowledge in the society with which he was acquainted, he concluded, in defiance of the strongest and clearest evidence, that the human mind can be cultivated by means of books alone. An Athenian citizen might possess very few volumes; and the largest library to which he had access might be much less valuable than Johnson’s bookcase in Bolt Court. But the Athenian might pass every morning in conversation with Socrates, and might hear Pericles speak four or five times every month. He saw the plays of Sophocles and Aristophanes: he walked amidst the friezes of Phidias and the paintings of Zeuxis: he knew by heart the choruses of Æschylus: he heard the rhapsodist at the corner of the street reciting the shield of Achilles or the death of Argus; he was a legislator, conversant with high questions of alliance, revenue, and war: he was a soldier, trained under a liberal and generous discipline: he was a judge, compelled every day to weigh the effect of opposite arguments. These things were in themselves an education; an education eminently fitted, not, indeed, to form exact or profound thinkers, but to give quickness to the perceptions, delicacy to the taste, fluency to the expression, and politeness to the manners. All this was overlooked. An Athenian who did not improve his mind by reading was, in Johnson’s opinion, much such a person as a Cockney who made his mark; much such a person as black Frank before he went to school; and far inferior to a parish clerk or a printer’s devil."

"Of the great French writers of his own time, Montesquieu is the only one of whom [Walpole] speaks with enthusiasm. And even of Montesquieu he speaks with less enthusiasm than of that abject thing, Crébillon the younger, a scribbler as licentious as Louvet and as dull as Rapin. A man must be strangely constituted who can take interest in pedantic journals of the blockades laid by the Duke of A. to the hearts of the Marquise de B. and the Comtesse de C. This trash Walpole extols in language sufficiently high for the merits of Don Quixote, He wished to possess a likeness of Crébillon; and Liotard, the first painter of miniatures then living, was employed to preserve the features of the profligate dunce. The admirer of the Sopha and of the Lettres Athéniennes had little respect to spare for the men who were then at the head of French literature. He kept carefully out of their way. He tried to keep other people from paying them any attention. He could not deny that Voltaire and Rousseau were clever men; but he took every opportunity for depreciating them. Of D’Alembert he spoke with a contempt which, when the intellectual powers of the two men are compared, seems exquisitely ridiculous. D’Alembert complained that he was accused of having written Walpole’s squib against Rousseau. I hope, says Walpole, that nobody will attribute D’Alembert’s works to me. He was in little danger."

"Of those powers we must form our estimate chiefly from tradition; for of all the eminent speakers of the last age Pitt has suffered most from the reporters. Even while he was still living, critics remarked that his eloquence could not be preserved, that he must be heard to be appreciated. They more than once applied to him the sentence in which Tacitus describes the fate of a senator whose rhetoric was admired in the Augustan age: Haterii canorum illud et profluens cum ipso simul exstinctum est. There is, however, abundant evidence that nature had bestowed on Pitt the talents of a great orator; and those talents had been developed in a very peculiar manner, first by his education, and secondly by the high official position to which he rose early, and in which he passed the greater part of his public life."

"Of the service which his Essays rendered to morality it is difficult to speak too highly. It is true that, when the Tatler appeared, that age of outrageous profaneness and licentiousness which followed the Restoration had passed away. Jeremy Collier had shamed the theatres into something which, compared with the excesses of Etherege and Wycherley, might be called decency. Yet there still lingered in the public mind a pernicious notion that there was some connection between genius and profligacy, between the domestic virtues and the sullen formality of the Puritans. That error it is the glory of Addison to have dispelled. He taught the nation that the faith and the morality of Hale and Tillotson might be found in company with wit more sparkling than the wit of Congreve, and with humour richer than the humour of Vanbrugh. So effectually, indeed, did he retort on vice the mockery which had recently been directed against virtue, that, since his time, the open violation of decency has always been considered among us as the mark of a fool. And this revolution, the greatest and most salutary ever effected by any satirist, he accomplished, be it remembered, without writing one personal lampoon."

"Of the small pieces which were presented to chancellors and princes it would scarcely be fair to speak. The greatest advantage which the Fine Arts derive from the extension of knowledge is, that the patronage of individuals becomes unnecessary. Some writers still affect to regret the age of patronage. None but bad writers have reason to regret it. It is always an age of general ignorance. Where ten thousand readers are eager for the appearance of a book, a small contribution from each makes up a splendid remuneration for the author. Where literature is a luxury, confined to few, each of them must pay high. If the Empress Catherine, for example, wanted an epic poem, she must have wholly supported the poet;—just as, in a remote country village, a man who wants a mutton-chop is sometimes forced to take the whole sheep;—a thing which never happens where the demand is large. But men who pay largely for the gratification of their taste will expect to have it united with some gratification to their vanity. Flattery is carried to a shameless extent; and the habit of flattery almost inevitably introduces a false taste into composition. Its language is made up of hyperbolical commonplaces, offensive from their triteness, still more offensive from their extravagance. In no school is the trick of overstepping the modesty of nature so speedily acquired. The writer, accustomed to find exaggeration acceptable and necessary on one subject, uses it on all."

"Of those scholars who have disdained to confine themselves to verbal criticism few have been successful. The ancient languages have, generally, a magical influence on their faculties. They were fools called into a circle by Greek invocations. The Iliad and Æneid were to them not books, but curiosities, or rather reliques. They no more admired those works for their merits than a good Catholic venerates the house of the Virgin at Loretto for its architecture. Whatever was classical was good. Homer was a great poet, and so was Callimachus. The epistles of Cicero were fine, and so were those of Phalaris. Even with respect to questions of evidence they fell into the same error. The authority of all narrations, written in Greek or Latin, was the same with them. It never crossed their minds that the lapse of five hundred years, or the distance of five hundred leagues, could affect the accuracy of a narration;—that Livy could be a less veracious historian than Polybius;—or that Plutarch could know less about the friends of Xenophon than Xenophon himself. Deceived by the distance of time, they seem to consider all the Classics as contemporaries; just as I have known people in England, deceived by the distance of place, take it for granted that all persons who live in India are neighbours, and ask an inhabitant of Bombay about the health of an acquaintance at Calcutta. It is to be hoped that no barbarian deluge will ever again pass over Europe. But should such a calamity happen, it seems not improbable that some future Rollin or Gillies will compile a history of England from Miss Porter’s Scottish Chiefs, Miss Lee’s Recess, and Sir Nathaniel Wraxall’s Memoirs."

"Of the two kinds of composition into which history has been thus divided, the one may be compared to a map, the other to a painted landscape. The picture, though it places the country before us, does not enable us to ascertain with accuracy the dimensions, the distances, and the angles. The map is not a work of imitative art. It presents no scene to the imagination; but it gives us exact information as to the bearings of the various points, and is a more useful companion to the traveller or the general than the painted landscape could be, though it were the grandest that ever Rosa peopled with outlaws, or the sweetest over which Claude ever poured the mellow effulgence of a setting sun."

"Office of itself does much to equalize politicians. It by no means brings all characters to a level: but it does bring high characters down and low characters up towards a common standard. In power the most patriotic and most enlightened statesman finds that he must disappoint the expectations of his admirers: that if he effects any good, he must effect it by compromise; that he must relinquish many favourite schemes; that he must bear with many abuses. On the other hand, power turns the very vices of the most worthless adventurer, his selfish ambition, his sordid cupidity, his vanity, his cowardice, into a sort of public spirit. The most greedy and cruel wrecker that ever put up false lights to lure mariners to their destruction will do his best to preserve a ship from going to pieces on the rocks, if he is taken on board of her and made pilot: and so the must profligate Chancellor of the Exchequer must wish that trade may flourish, that the revenue may come in well, and that he may be able to take taxes off instead of putting them on. The most profligate First Lord of the Admiralty must wish to receive news of a victory like that of the Nile rather than of a mutiny like that at the Nore. There is therefore a limit to the evil which is to be apprehended from the worst ministry that is likely ever to exist in England. But to the evil of having no ministry, to the evil of having a House of Commons permanently at war with the executive government, there is absolutely no limit. This was signally proved in 1699 and 1700."